SelfDefinition.Org

The Practice of Zen

Garma C.C. Chang

Chang Chen-chi (1920-1988)

2. Discourses of Master Tsung Kao [1]

Esta página en español: ..discursos-tsung-kao.htm

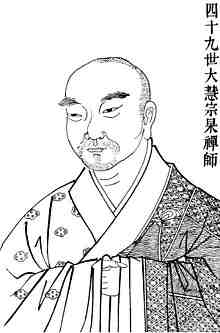

[1. Ta-hui Tsung-kao, 12th century: Dahui_

To Lee Hsien Chen:

Tsung Kao aka Dahui Zonggao

... Buddha says, "If one wants to know the Realm of Buddha, he should purify his own mind like the void space."... You must know that this Realm is not gained through any exalted religious practice. What one should do is to cleanse the defilements of passion and delusion that have lain hidden in the roots of his own mind from the very no-beginning-time. His mind should be vast and expansive like space itself, far away from mere psychic notions. All wild and distracting thoughts are illusory, unreal, and void-like. Practicing in this manner, the wonder of the effortless mind will then naturally and spontaneously react to all conditions without any obstacle.

To Huang Po Cheng:

The so-called No-mind [Chinese: Wu hsin] is not like clay, wood, or stone, that is, utterly devoid of consciousness; nor does the term imply that the mind stands still without any reaction when it contacts objects or circumstances in the world. It does not adhere to anything, but is natural and spontaneous at all times and under all circumstances. There is nothing impure within it; neither docs it remain in a state of impurity. When one observes his body and mind, he sees them as magic shadows or as a dream. Nor does he abide in this magic and dreamlike state. ... When he reaches this point, then he can be considered as having arrived at the true state of No-mind.

To Hsu Tun Li:

Conceptualization is a deadly hindrance to the Zen yogis, more injurious than poisonous snakes or fierce beasts ... [Endnote 2-7] Brilliant and intellectual persons always abide in the cave of conceptualization; they can never get away from it in all their activities. As months and years pass they become more deeply engulfed in it. Unknowingly the mind and conceptualization gradually become of a piece. Even if one wants to get away from it, he finds it is impossible. Therefore, I say, poisonous snakes and beasts are avoidable, but there is no way to escape from mental conceptualization. Intellectuals and noble gentlemen are apt to search for the nongrasp-able Dharma with a "grasping mind." What is this "grasping mind"? The grasping mind is the very one that is capable of thinking and calculating – the one that is intelligent and brilliant. What is the nongrasp-able Dharma? The nongraspable Dharma is that which cannot be conceived, measured, or comprehended intellectually.... Yung Chia says, "The real nature of blindness is the real nature of Buddha. This illusory [physical] body is the Dharmakaya itself. When one realizes the Dharmakaya, [he sees] that nothing exists. This is called The Original Primeval Buddhahood.'"

With this understanding, if one abruptly throws his mind into the abyss where mind and thought cannot reach, he will then behold the absolute, void Dharmakaya. This is where one emancipates oneself from Sangsara....

People have always been abiding in the cave of thought and intellection. As soon as they hear me say "Get rid of thinking," they are dazed and lost and do not know where to go. They should know that right at the moment when this very feeling of loss and stupefaction arises is the best time for them to attain realization [literally, for them to release their body and life].

In Answer to Lu Shun Yuan:

There is no definite standard by which one can measure the forces of Dharma and of Karma. The critical point is to see whether one can be aware of his mind-essence in all activities at all times. Here one must know that both the force of Karma and the force of Dharma are illusory. If a man insists on ridding himself of Karma and taking up Dharma, I would say that this man does not understand Buddhism. If one can really destroy Karma, he will find that the Dharma is also unreal. Ordinary people are small in courage and narrow in perspective; they always infer that this practice is easy, and that that one is difficult. They do not know that the discriminating mind which deems things to be easy or difficult, which attaches itself to things or detaches itself from them, is itself the very mind that drags us down into Sangsara. If this mind is not uprooted, no liberation is possible.

To Tseng Tien Yu:

From your letter I know that you can work on Zen during all daily activities and official business without being interrupted or entangled by them. Even though you may be submerged in a torrent of worldly affairs, you are always able to keep your mindfulness alert. This is indeed remarkable. I am very pleased with your vigorous effort and the increasing strength of your aspiration to Tao. However, you must realize that the tumult of Sangsara is like a great fireball; there is no ending to it. Therefore, right at the moment of engaging in any turbulent activity, you must not forget the straw seats and the bamboo chairs. [Endnote 2-8]

The superior work you have done so industriously in quietness should be applied when you are submerged in the tumult of your daily life. If you find it difficult to do so, it is most likely that you have not gained very much from the work in quietude. If you are convinced that meditating in quietude is better than meditating in activity, you are then [falling into the trap] of searching for reality through destroying manifestations, or of departing from causation to pursue Nirvana. The very moment when you are craving quiet and abhoring turbulence is the best time to put all your strength into the Work. Suddenly the realization which you have searched so hard for in your quiet meditations will break upon you right in the midst of the turbulence. Oh, this power, gained from breaking-through, is thousands and millions of times greater than that generated by quiet meditation on your straw seat and bamboo chair!

To Huang Po Cheng:

It is easy for Zen yogis to empty the [outer] things, but it is difficult for them to empty their [inner] minds. If one can empty only the things and not the mind, this proves that his mind is still under the subjugation of the things. If one can empty his mind, the things will be emptied automatically. If one thinks he has emptied his mind, but then raises the second thought of emptying the things, this proves clearly that his mind has never been really emptied; he is still under the subjugation of outer things. If this mind itself is emptied, what things could possibly exist outside of it?

Only after one has utterly and completely broken through is he qualified to say "Passion-desire in Enlightenment and blindness is the Great Wisdom."

The originally vast, serene, and marvelous mind is all-pure and illuminatingly all-inclusive. Nothing can hinder it; it is free as the firmament. Even the name "Buddha" cannot encompass it. How is it then possible to find passion-desires or erroneous views in it, in opposition to the idea of "Buddha"?

This is like the sun shining in the blue sky – clear and bright, unmovable and immutable, neither increasing nor decreasing. In all daily activities it illuminates all places and shines out from all things. If you want to grasp it, it runs away from you; but if you cast it away, it continues to exist there all the time.

To Hsu Tun Li:

When working on Zen, one should dig into it with all his mind and heart. Whether you are happy or angry, in high or lowly surroundings, drinking tea or eating dinner, at home with your wife and children, meeting with guests, on duty in the office, attending a party or a wedding celebration, [or active in any other way], you should always be alert and mindful of the Work, because all of these occasions are first-class opportunities for self-awakening. Formerly the High Commissioner, Lee Wen Hoo, gained thorough Enlightenment while he was holding this high position in the government. Young Wen Kung gained his Zen awakening while he was working in the Royal Institute of Study. Chang Wu Yuen gained his while he held the office of the Commissioner of Transport in Chiang Hsi Province. These three great laymen have indeed set for us an example of the realization of Truth without renunciation of the world. Did they struggle at all to shun their wives, resign from their offices and positions, gnaw the roots of vegetables, practice ascetism and frugality, avoid disturbance, and seek quiet [and seclusion] to gain their enlightenment?

[The difference between the way that a layman and a monk must work on Zen is that] the monk strives to break through from the outside to the inside, while the layman must break through from the inside to the outside. Trying to break through from the outside requires little, but from the inside, great power. Thus the layman requires much more power to get the Work done because of the unfavorable conditions under which he must work.... The great power generated from ttiis difficult struggle enables him to make a much more thorough and mighty turnabout than the monk; the monk, on the other hand, can only make a smaller turn because, working under far more favorable conditions, he gains less power [in the process].

To Hsu Shou Yuan:

To measure the self-mind with intellection and conceptualization is as futile as dreaming. When the consciousness, wholly liberated in tranquility and having no thought whatsoever, moves on, it is called "right realization." When one has attained this correct realization, one is then able to become tranquilly natural at all times and in all activities – while walking or sitting, standing or sleeping, talking or remaining silent. One will never be confused under any circumstance. Thought and thoughtlessness both become pure.

Alas! I explain [the matter] to you in all these words simply because I am helpless! If I say in its literal sense that there is something to work with, I then betray youl

In Answer to Lu Lung Li:

Penetrate to the bottom of your mind and ask, "Where does this very thought of craving for wealth and glory come from? Where will the thinker go afterwards?" You will find that you cannot answer either of these two questions. Then you will feel perplexed. That is the moment to look at the Hua Tou, "Dry dung!" Do not think of anything else. Just continue to hold to this Hua Tou. ... Then suddenly you will lose all your mental resources and awake.

The worst thing is to quote the scriptures and give explanations or elaborations to prove your "understanding." No matter how well you may put things together, you are but trying to find a living being among ghosts! If one cannot break up the "doubt-sensation," he is bound by life and death; if he can break it up, his Sangsaric mind will come to its end. If the Sangsaric mind is exhausted, the ideas of Buddha and Dharma will also come to an end. Then, since even the ideas of Buddha and Dharma are no more, from whence could arise the ideas of passion-desires and sentient beings?

To Yung Mao Shihi:

If you have made up your mind to practice Zen, the first and most important thing is: Do not hurry! If you hurry, you will only be delayed. Nor should you be too lax, for then you will become lazy. The work should be carried out as a musician adjusts the strings of his harp – neither too tightly nor too loosely.

What you should do is look at that which understands and makes decisions and judgments. Just look at it all the time in your daily round. With great determination in your heart, try to find out from whence all these mental activities come. By looking at it here and there, now and then, the things with which you are familiar and are in the habit of doing gradually become unfamiliar; and the things with which you are not familiar [Zen Work] gradually become familiar. When you find your Work coming easily, you are doing very well in it. And by the same token, whenever the Work is being done well, you will feel that it is coming easily for you. A critical stage is thus reached.

To Tseng Tien Yu:

The one who distinguishes, judges, and makes decisions is sentient consciousness. This is the one who forever wanders in Sangsara. Not being aware that this sentient consciousness is a dangerous pitfall, many Zen students nowadays cling to it and deem it to be the Tao. They rise and fall like [a piece of driftwood] in the sea. But if one can abruptly put everything down, stripped of all thought and deliberations, suddenly he feels as if he had stumbled over a stone and stepped upon his own nose. Instantaneously he realizes that this sentient consciousness is the true, void, marvelous Wisdom itself. No other wisdom than this can be obtained. ... This is like a man, in his confusion, mistakenly regarding the east as the west. But when he awakens, he realizes that the "west" is the east. There is no other east to be found. This true, void, marvelous Wisdom lives on eternally like space. Have you ever seen anything that can impede space? Though it is not impeded by anything, neither does it hinder anything from moving on in its embrace.

To Hsieh Kuo Jan:

If one can instantaneously realize the truth of nonexistence without departing from lust, hate, and ignorance, he can grasp the weapons of the Demon King and use them in an opposite way. He can then turn these evil companions into angels protecting the Dharma. This is not done in an artificial or compulsory way. This is the nature of the Dharma itself.

To Hsiung Hsu Ya:

If in all your daily activities and contacts you can keep your awareness or do away with that which is "unaware," gradually as the days and months go by your mind will naturally become smoothed out into one continuous, whole piece. What exactly do I mean by "contacts"? I mean that when you are angry or happy, attending to your official business, entertaining your guests, sitting with your wife and children, thinking of good or evil things – all these occasions are good opportunities to bring forth the "sudden eruption." This is of the utmost importance; bear it in your mind.

To Hsieh Kuo Jan:

The Elders in the past said, "Just put your whole mind to it and work hard. The Dharma will never let you down."

To Chen Chi Jen:

When you are involved in turmoils and excitement which you have no way of avoiding or eschewing, you should know that this is the very best time to work on Zen. If, instead, you make an effort to suppress or correct your thoughts, you are getting far away from Zen. The worst thing a student can do is to attempt to correct or suppress his thoughts during inescapable circumstances. Masters in ancient times have said,

No distinguishment whatsoever arises –

Only the void-illumination

Reflects all manifestations within oneself.

Bear this in mind, bear this in mind!

If you use one iota of strength to make the slightest effort to attain Enlightenment, you will never get it. If you make such an effort, you are trying to grasp space with your hands, which is useless and a waste of your time!