SelfDefinition.Org

The Practice of Zen

Garma C.C. Chang

Chang Chen-chi (1920-1988)

II. THE PRACTICE OF ZEN

Esta página en español: ..analysis-general-de-la-practica-del-zen.htm

A General Review of Zen Practice

Zen practice is not a subject that uninitiated scholars can deal with competently through mere intellection or pedantry. Only those who have had the experience itself can discuss this topic with authoritative intimacy.

It would be folly, therefore, not to follow the advice of the accomplished Zen Masters, not to reflect on their life stories – stories that abound with accounts of the actual experience gained during their struggles in Zen. The discourses and autobiographies of the Zen Masters have proved, in past centuries, to be invaluable documents for Zen students, and they are accepted and cherished by all Zen seekers in the Orient as infallible guides and companions on the journey toward Enlightenment.

To those who cannot find access to a competent Zen Master – a not uncommon case nowadays – these documents should be of inestimable value and usefulness.

I have therefore translated herein a number of the most popular and important discourses and autobiographies of the reputable Zen Masters, to show the reader in what manner they practiced Zen, through what efforts they gained their Enlightenment, and, above all, what they have to say to us on these vital subjects.

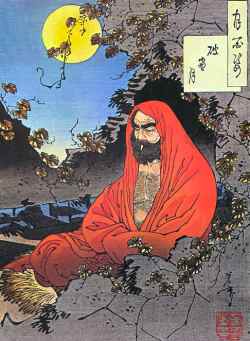

Bodhidharma

In order to help the reader to understand these discourses with greater ease, I shall here give a very brief account of the history of Zen, and also point out several important facts concerning its practice.

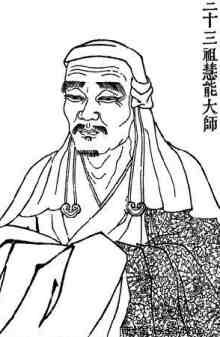

Ch'an (Zen) was first introduced into China by the Indian monk Bodhidharma (470-543), [1] in the early part of the sixth century, and was established by the Sixth Patriarch, Hui Neng (638-713), [2] around the beginning of the eighth century.

[1. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/

[2. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Huineng ]

Hui Neng had several prominent disciples, two of whom, Huai Jang (?-740), and Hsing Ssu (?-775), were extremely influential. Each of them had one outstanding disciple, namely Ma Tsu (?-788) and Shih Tou (700-790), respectively; and they, in turn, had several remarkable disciples who founded, either directly or indirectly, the five major Zen sects existing in those times, i.e., Lin Chi, Tsao Tung, I Yang, Yun Men, and Fa Yen. As time went on all five of these major sects were consolidated into either the Tsao Tung (Japanese: Soto) [3] or the Lin Chi (Japanese: Rinzai) [4] sect. The Tsao Tung and Lin Chi are thus the only sects of Zen Buddhism extant today.

[3. en.wikipedia.org/

[4. en.wikipedia.org/

Hui Neng (638-713)

Zen, after the period of Hui Neng, spread to almost every corner of China and gradually became the most popular school of Buddhism in that country. It was widely accepted and practiced by both monks and laymen from all walks of life. Through the efforts of Hui Neng and his disciples, the unique styles and traditions of Zen, which I have outlined briefly in the preceding chapter, gradually emerged.

The first two hundred years of Zen produced in succession six Patriarchs – Bodhidharma being the first and Hui Neng the sixth. During this time Zen kept its plain and original Indian style without the introduction of any radical or bizarre elements such as are found in the later periods of Zen history. In this early period Zen was unembellished, understandable, outspoken, and matter-of-fact. Because of a lack of documentation concerning Zen practice in this early period, we do not know very clearly the exact manner in which Zen was actually practiced. We can only say with assurance that there were no koan exercises, and no shouting, kicking, crying, or beating "performances" such as those found at the present time. Several things, however, happened during this epoch. First, certain verbal instructions concerning Zen practice must have been handed down through the succession from Bodhidharma to Hui Neng. Second, these instructions must have been practical and applicable teachings which were qualitatively different from the ungraspable koan-typc exercises characteristic of later times. Third, Zen practice must have followed mainly the Indian tradition, largely identical with the teaching of Mahamudra, [Endnote 2-1] which was introduced from India into Tibet and has been widely practiced in that country since the ninth century. At present the Tsao Tung sect is perhaps the only Zen sect that still retains some Indian elements in its teaching, and is probably the only source from which we may deduce some information about the original practice of Zen.

There exists, however, a great dearth of documentation for the practical instructions which must have been given by the Tsao Tung Masters. One of the reasons that may have contributed to this shortage of written material is the "secret tradition" of the Tsao Tung sect, which discourages its followers from putting verbal instructions down in writing. Thus time has erased all traces of many such oral teachings.

In the old days many Zen Masters of the Tsao Tung sect taught their disciples in a most secret way. The phrase "Enter into the Master's room and receive the secret instruction" (Chinese: ju shih mi shou) [g] was widely used. This practice was much criticized by the followers of the Lin Chi sect, notably by the eloquent Master Tsung Kao (1089-1163).

[g. Letters refer to the Appendix of Chinese characters.]

For many generations the Tsao Tung [Sōtō] and the Lin Chi [Rinzai] have been the two "rival" Zen sects, each offering, in certain respects, a different approach to the Zen practices. Because of these different approaches the individual student can choose the one that suits him best and helps him most. The superiority or preferability of the plain, tangible, "explicit" Indian approach to Zen, advocated by the Tsao Tung sect, over the bewildering, ungraspable, and "esoteric" Chinese Ch'an approach represented by the Lin Chi sect, has always been a controversial subject.

Objectively speaking, both of these approaches possess their merits and demerits, their advantages as well as their disadvantages. If one wants to by-pass the recondite and cryptic Zen elements and try to graph directly a plain and tangible instruction that is genuinely practical, the Tsao Tung approach is probably the more suitable. But if one wants to penetrate more deeply to the core of Zen, and is willing to accept the initial hardships and frustrations, the approach of the Lin Chi sect – the most prevalent and popular Zen sect in both China and Japan today – is probably preferable.

I personally do not think the Tsao Tung approach is a poor one, although it may not produce a realization as deep and as "free" as that of the Lin Chi in the beginning stages. However, the plain, tangible approach of Tsao Tung may be much better suited to the people of the twentieth century. This is mainly because the koan exercise – the mainstay if not the only stay of the Lin Chi practice – is too difficult and too uncongenial for the modern mind. Besides, in practicing Zen by means of the koan exercise, one must constantly rely on a competent Zen Master from beginning to end. This again presents a difficult problem. A third objection to the koan exercise is that it tends to create a constant strain on the mind, which will not relieve, but only intensify, the deadly mental tensions which many people suffer in this atomic age. Nevertheless, if one can receive constant guidance under a competent Zen Master and live in a favorable environment, the koan exercise may prove to be a better method in the long run.

Nowadays, when Zen practice is mentioned, people immediately think of the koan (or Hua Tou) exercise as though there were no other way of practicing Zen. Nothing could be more mistaken. The Hua Tou exercise did not gain its popularity until the latter part of the Sung Dynasty in the eleventh century. From Bodhidharma to Hui Neng, and from Hui Neng all the way through Lin Chi and Tang Shan – a total period of approximately four hundred years – no established system of Hua Tou exercises can be traced. The outstanding Zen Masters of this period were great "artists"; they were very flexible and versatile in their teaching, and never confined themselves to any one system. It was mainly through the eloquent Master Tsung Kao (1089-1163) that the Hua Tou exercise became the most popular, if not the only, means by which Zen students have practiced during the past eight centuries.

Here the interesting question is. How, before the popularization and standardization of the koan exercise, did students of older times practice Zen? How did those great figures, Hui Neng, Ma Tsu, Huang Po, and Lin Chi, themselves practice Zen? We have sufficient reason to believe that in the old days the "serene-reflection" type of meditation now found in the teaching of the Tsao Tung sect was probably the mainstay of Zen meditation techniques.

Now precisely what are the teachings of both sects; and exactly how does the Tsao Tung approach differ from that of the Lin Chi? To answer these questions as concisely as possible, the Tsao Tung approach to Zen practice is to teach the student how to observe his own mind in tranquility. The Lin Chi approach, on the other hand, is to put the student's mind to work on the "solution" of an unsolvable problem known as the koan, or Hua Tou, exercise. The former may be regarded as overt or exoteric, the latter as covert or esoteric. If, in the beginning, the student can be properly guided by a good teacher, the former approach is not too difficult to practice. If one can get the "verbal instructions" from an experienced Zen Master he will soon learn how to "observe the mind in tranquility" or, in Zen idiom, how to practice the "serene-reflection" type of meditation. [Endnote 2-2] In contrast to this "serene-reflection" practice of the Tsao Tung school, the Lin Chi approach of the koan exercise is completely out of the beginner's reach. He is put purposely into absolute darkness until the light unexpectedly dawns upon him.

Before discussing koans in detail, let us comment on the Tsao Tung technique of "observing one's mind in tranquility" – the original and more "orthodox" Zen practice which has been neglected for so long in the overwhelming attention given to koan exercises.

Practicing Zen through Observing One's Mind in Tranquility

The Zen practice of the Tsao Tung [Sōtō] School can be summed up in these two words: "serene reflection" (Chinese: mo chao). This is clearly shown in the poem from the "Notes on Serene-Reflection," by the famous Zen Master, Hung Chih, of the Tsao Tung school:

Silently and serenely one forgets all words;

Clearly and vividly That appears before him.

When one realizes it, it is vast and without edges;

In its Essence, one is clearly aware.

Singularly reflecting is this bright awareness,

Full of wonder is this pure reflection.

Dew and the moon,

Stars and streams,

Snow on pine trees,

And clouds hovering on the mountain peaks –

From darkness, they all become glowingly bright;

From obscurity, they all turn to resplendent light.

Infinite wonder permeates this serenity;

In this Reflection all intentional efforts vanish.

Serenity is the final word [of all teachings];

Reflection is the response to all [manifestations].

Devoid of any effort.

This response is natural and spontaneous

Disharmony will arise

If in reflection there is no serenity;

All will become wasteful and secondary

If in serenity there is no reflection

The Truth of serene-reflection

Is perfect and complete.

Oh look! The hundred rivers flow

In tumbling torrents

To the great ocean!

Without some explanations and comments on this poem, the meaning of "serene-reflection" may still be enigmatic to many readers. The Chinese word, mo, means "silent" or "serene"; chao means "to reflect" or "to observe." Mo chao may thus be translated as "serene-reflection" or "serene-observation." But both the "serene" and the "reflection" have special meanings here and should not be understood in their common connotations. The meaning of "serene" goes much deeper than mere "calmness" or "quietude"; it implies transcendency over all words and thoughts, denoting a state of "beyond," of pervasive peace. The meaning of "reflection" likewise goes much deeper than its ordinary sense of "contemplation of a problem or an idea." It has no savor of mental activity or of contemplative thought, but is a mirror-like clear awareness, ever illuminating and bright in its pure self-experience.

To speak even more concisely, "serene" means the tranquility of no-thought (Chinese: wu nien), and "reflection" means vivid and clear awareness. Therefore, serene-reflection is clear awareness in the tranquility of no-thought. This is what the Diamond Sutra [5] meant by "not dwelling on any object, yet the mind arises."

[5. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/

The great problem here is, how can one put his mind into such a state? To do so requires verbal instruction and special training at the hands of a teacher. The "wisdom eye" of the disciple must first be opened, otherwise he will never know how to bring his mind to the state of serene-reflection. If one knows how to practice this meditation, he has already accomplished something in Zen. The uninitiated never know how to do this work. This serene-reflection meditation of the Tsao Tung sect, therefore, is not an ordinary exercise of quietism or stillness. It is the meditation of Zen, of Prajnaparamita. [6] Careful study of the preceding poem will show that the intuitive and transcendental "Zen elements" are unmistakably there.

[6. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/

The best way to learn this meditation is to train under a competent Zen Master. If, however, you are unable to find one, you should try to work through the following "Ten Suggestions" – the quintessential instructions on Zen practice that the author has learned through great difficulties and long years of Zen study. It is his sincerest hope that they will be valued, cherished, and practiced by some serious Zen students in the West.

The Ten Suggestions on Zen Practice:

1. Look inwardly at your state of mind before any thought arises.

2. When any thought does arise, cut it right off and bring your mind back to the work.

3. Try to look at the mind all the time.

4. Try to remember this "looking-sensation" in daily activities.

5. Try to put your mind into a state as though you had just been shocked.

6. Meditate as frequently as possible.

7. Practice with your Zen friends the circle-running exercise (as found in Chapter II, in the "Discourses of Master Hsu Yun").

8. In the midst of the most tumultuous activities, stop and look at the mind for a moment.

9. Meditate for brief periods with the eyes wide-open.

10. Read and reread as often as possible the Prajnaparamita Sutras, such as the Diamond and Heart Sutras, the Prajna of Eight Thousand Verses, the Mahaprajnaparamita Sutra, etc.

Hard work on these ten suggestions should enable anyone to find out for himself what "serene-reflection" means.

Practicing Zen through the Koan Exercise

What is the koan exercise? "Koan" is the Japanese pronunciation of the Chinese phrase kung-an; and the original meaning of kung-an is "the document of an official transaction on the desk." But the term is used by Zen Buddhists in a slightly different manner in that it denotes a certain dialogue or event that has taken place between the Zen Master and his student. For example, "A monk asked Master Tung Shan, 'Who is Buddha?' [To which the Master replied] 'Three chin [measures] of flax!'"; or, "A monk asked Master Chao Chou, 'What is the meaning of Bodhidharma's coming from the West?' 'The cypress tree in the courtyard'." All the Zen stories, both short and long, related in the preceding chapter are koans. In short, "koan" means a Zen story, a Zen situation, or a Zen problem. The koan exercise usually implies working on the solution of a Zen problem such as "who is the one who recites the name of Buddha?"; or "All things are reducible to one; to what is the one reducible?"; or the single word Wu (meaning "No" or "Nothing"); and the like. Since "koan" has now become almost an established term, widely used in the West, it seems unnecessary always to use in its place the original Chinese term Hua Tou. Both "koan" and Hua Tou are, therefore, used here in the general and in the specific sense, respectively. In China Zen Buddhists seldom use the term "koan exercise"; instead, they say, "Hua Tou exercise," or "tsen Hua Tou," [h] meaning "to work on a Hua Tou." What is this Hua Tou? Hua means "talking," "remark," or "a sentence"; tou means "ends," applicable either in the sense of the beginning or the ending of something; hua tou thus means "the ends of a sentence." For example, "Who is the one who recites the name of Buddha?" is a sentence, the first "end" of which is the single word "Who." To put one's mind into this single word "who," and try to find the solution of the original question, is an example of the "Hua Tou exercise." "Koan," however, is used in a much wider sense than Hua Tou, referring to the whole situation or event, while Hua Tou simply means the ends or, more specifically, the critical words or point of the question. To give another example, "A monk asked Master Chao Chou, 'Does a dog have the Buddha nature?' Chao Chou answered, 'Wu!' [meaning 'No!']." This dialogue is called a "koan," but the Zen student who is working on this koan should not think of both the question and the answer. Instead he should put all his mind into the single word "Wu." [Endnote 2-3] This one word, "Wu," [i] is called the Hua Tou. There are also other interpretations for the meaning of Hua Tou, but the above sufficiently serves our present purpose.

How is the koan exercise practiced? When working at it, what should be avoided and what adhered to, what experiences will one have, and what will one accomplish thereby? The answers will be found in the Zen Masters' discourses and autobiographies which follow. They have been carefully selected from many primary Zen sources.