SelfDefinition.Org

The Practice of Zen

Garma C.C. Chang

Chang Chen-chi (1920-1988)

Discourses of Four Zen Masters

Esta página en español: ..cuatro-maestros-discurso-hsu-yun.htm

1. Discourses of Master Hsu Yun

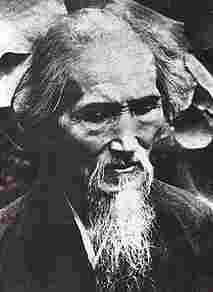

Xuyun (1840?-1959)

Master Hsu Yun [Xuyun] is the most celebrated living Zen teacher in China. He is, at this writing, a hundred and nineteen years old, but still healthy in body and alert in mind. He has given instruction to thousands of disciples and, in the past few decades, has established a great many monasteries in different parts of China. His life story is full of interesting episodes, and he is regarded as the most exemplary authority on Zen in modern China. The following sermons were given by him some years ago, when he led a number of Zen disciples in the practice of the customary "Seven Days' Meditation" [Endnote 2-4] at the Jade Buddha Monastery in Shanghai.

The First Day of the First Period, January 9th, 7 p.m. [Endnote 2-5]

After making obeisance to His Reverence Hsu Yun, the supervising monks invited him to come to the Meditation Hall of the monastery. He then stood in the center of the hall, while the supervisors, one of whom held a [warning] slapping board, stood in two rows on each side of the Master. The disciples in attendance, who had vowed to join this Seven Days' Meditation, and who had come from all parts of the country, stood about him in a large circle. Then the Revered Master raised his own slapping board and addressed the assembled company as follows: "This is the new month of the New Year, and now, fortunately, we can all join this Seven Days' Meditation practice. This is the place to learn the teaching of Not-Doing (Wu Wei). 'Not-Doing' means that there is absolutely nothing to be done or to be learned. Alas! Whatever I can say about 'nothingness' will miss the point. Oh, friends and disciples, if you do not attach yourselves to the Ten Thousand Things with your minds, you will find that the life-spark will emanate from everything.

"Today is the first day of our Meditation. Friends, what do you say? Ah-h-h!"

Then after a long silence, the Master cried: "Go!" Immediately all the disciples, responding to his call, followed him, running in a large circle. After they had run for a number of rounds a supervising monk made the "stopping signal" by suddenly whacking the board on a table, making a loud slapping noise. Instantly all the runners stopped and stood still. After a pause they all sat down on their seats in the cross-legged posture. Then the entire hall became deadly quiet; not the slightest sound could be heard, as though they were in some deep mountain fastness. This silent meditation lasted for more than an hour. Then everyone rose from his seat and the circling exercise started again. After running a few more rounds, all suddenly stopped once more when they heard the slapping board make the signal.

Then the Master addressed the company as follows: "The Head Monk in this monastery is very kind and compassionate. It was through his sincere efforts that this Seven Days' Meditation was made possible. All the elders in the Order, and you lay-patrons as well, are diligent and inspired in the work of Tao. I was requested by all of you to lead the group in this Seven Days' Meditation. I feel greatly honored and inspired on this wonderful occasion. But I have not been too well of late; therefore I cannot talk very long. Our Lord Buddha preached the Dharma for more than forty years, sometimes preaching explicitly, sometimes implicitly. His teachings are all recorded and expounded in the Three Great Canons. So what is the use of my making more talk? The most I can do, and the best, is to repeat the words of our Lord Buddha and the Patriarchs. In any case, we should know that the teaching of Zen is transmitted outside the regular Buddhist doctrine. This is illustrated most effectively in the first Zen koan. When Buddha held the flower in his hand and showed it to his disciples, no one in the assembly understood his purport except Mahakasyapa, [1] who smiled to indicate that he understood what Buddha meant. The Buddha then said, 'I have a treasure of the righteous Dharma, and the marvelous Mind of Nirvana – the true form without any form. I now impart it to you.' [2]

[1. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/

[2. This long-held traditional story is now regarded as an invention created to add weight to the Zen teachings, it having been considered insufficient to trace Zen back only to Hui Neng or Bodhidharma. The earliest written record of the story is a text dated 1077. Ref. Stuart Lachs, note 8.]

"Therefore you should understand that Zen is a teaching transmitted outside the regular channels of Buddhist doctrine, without resorting to many words or explanations. Zen is the highest and most direct teaching leading to instantaneous Enlightenment, providing one is capable of grasping it at once. Some people have mistakenly thought that the twenty odd Ch'ans (Dhyanas) mentioned in the Great Perfect Wisdom Sutra [3] comprise the whole of Ch'an [Zen]. This is utterly wrong. These Dhyanas are not the supreme ones.

[3. en.wikipedia.org/

"The work of our 'Ch'an' has no gradual processes or successive stages. This Ch'an is the supreme Ch'an of seeing one's Buddha-nature instantly. But if this is so, why should one bother to practice the so-called Seven Days' Meditation? [We must understand that] people's capacity to practice the Dharma is deteriorating all the time. Nowadays people have too many distracting thoughts in their minds. Therefore the Patriarchs have designed special methods and techniques, such as the Seven Days' Meditation Practice, the koan exercises, the circle-running exercise, and so forth, to cope with this condition and to help persons of lesser capacity.

"From the time of Mahakasyapa until now Zen has spanned some sixty to seventy generations. During the periods of Tang and Sung, Zen spread to every place under Heaven. How great and how glorious was Zen in those days! Alas! Compared to them, to what a pitiable state has Zen fallen now! Only Chin Shan [The Golden Mountain] Monastery, Kao Ming [High Heaven] Monastery, Pao Kuang [The Precious Light] Monastery, and several others still keep up the tradition of Zen. Therefore not many outstanding figures can be found in the Zen schools today.

"Once the Seventh Patriarch, Shen Hui, asked the Sixth Patriarch, Hui Neng, 'Through what practice should one work that one may not fall into a "category"?' The Sixth Patriarch replied, 'What have you been doing?' Shen Hui answered, 'I do not even practice the Holy Truth!' 'In that case, to what category do you belong?' 'Even the Holy Truth does not exist, so how can there be any category?' Hearing this answer, the Sixth Patriarch was impressed by Shen Hui's understanding.

"Now you and I, not being as highly endowed as the Patriarchs, are obliged to devise methods such as the Hua Tou practice, which teach us to work on a specifically chosen koan problem crystallized into a single sentence or Hua Tou. After the Sung Dynasty the Pure Land School became increasingly popular, and reciting the name of Buddha Amida became a widespread practice among the Buddhists. Under these circumstances, the great Zen Masters urged people to work on the Hua Tou of 'Who is the one who recites the name of Buddha?' This Hua Tou then became, and still remains, the most popular of all. But there are still many people who do not understand how to practice it. Some are foolish enough to recite repeatedly the sentence itself!

"This Hua Tou practice is not a matter of reciting the sentence or concentrating on it. It is to tsen the very nature of the sentence. Tsen means to look into penetratingly and to observe. In the meditation hall of any monastery we usually find the following admonition posted on the walls: 'Observe and look into your Hua Tou.' Here, 'to observe' means to look at in reverse, that is, to look backward; and 'look into' means to put your mind penetratingly into the Hua Tou. Our minds are used to going outside and sensing the things in the outer world. Tsen is to reverse this habit and to look inside. 'Who is the one who recites the name of Buddha?' is the hua, the sentence. But before the thought of this sentence ever arises, we have the tou (the end). To tsen this Hua Tou is to look into the very idea of 'Who?', to penetrate into the state before the thought ever arises, and to see what this state looks like. It is to observe from whence the very thought of 'Who' comes, to see what it looks like, and subtly and very gently to penetrate into it.

"During your circle-running exercise you should hold your neck straight so that it touches the back of your collar, and follow the person ahead of you closely. Keep your mind calm and smooth. Do not turn your head to look around, but to concentrate your mind on the Hua Tou. When you sit in meditation do not lift your chest too far upward by artificially swelling it. In breathing, do not pull the air up, nor press it down. Let your breath rise and fall in its natural rhythm. Collect all your six senses and put aside everything that may be in your mind. Think of nothing, but observe your Hua Tou. Never forget your Hua Tou. Your mind should never be rough or forceful, otherwise it will keep wandering, and can never calm down; but neither should you allow your mind to become dull and slothful, for then you will become drowsy, and as a consequence you will fall into the snare of the 'dead-void.'

"If you can always adhere to your Hua Tou, you will naturally and easily master the work. Thus, all your habitual thoughts will automatically be subdued. It is not an easy job for beginners to work well on the Hua Tou, but you should never become afraid or discouraged; neither should you cling to any thought of attaining Enlightenment, because you are right now practicing the Seven Days' Meditation, whose very purpose is to produce Enlightenment. Therefore any additional thought of attaining Enlightenment is as unnecessary and as foolish as to think of adding a head to the one you already have! You should not worry about it if at first you cannot work well on the Hua Tou; what you should do is just to keep remembering and observing it continuously. If any distracting thoughts arise, do not follow them up, but just recognize them for what they are. The proverb says well:

Do not worry about the arising of distracting thoughts,

But beware if your recognition of them

Arises too late!

"In the beginning everyone feels the distraction of continuously arising errant thoughts, and cannot remember the Hua Tou very well; but gradually, as time goes on, you will learn to take up the Hua Tou more easily. When that time comes you can take it up with ease and it will not escape you once during the entire hour. Then you will find the work is not difficult at all. I have talked a lot of nonsense today! Now all of you had better go and work hard on your Hua Tou."

The Second Day of the First Period, January 10th

The Master again addressed those in attendance, as follows:

"The Seven Days' Meditation is the best way to attain Enlightenment within a definite and predetermined period. In the old days, when people were better endowed, many Zen Buddhists did not pay special attention to this method. But during the Sung Dynasty it began to gain popularity. Due especially to its promotion by Emperor Yung Cheng during the Ching Dynasty, the method became widespread throughout China. Emperor Yung Cheng of the Ching Dynasty was a very advanced Zen Buddhist, and had great respect and admiration for the teaching of Zen. In his royal palace the Seven Days' Meditation was carried on frequently. Under his instruction some ten persons attained Enlightenment. For example, the Tien Hui Zen Master of the High Heaven Monastery at Yang Chow became enlightened under his teachings. This Emperor reformed the systems and rules of Zen monasteries, and also the Zen practices. Through him Zen was greatly revitalized, and many outstanding Masters flourished during his time.

"Now we are working on Ch'an. What is Ch'an? It is called, in Sanskrit, Dhyana – the practice of deep concentration or contemplation. There are many different kinds of it, such as Hinayana and Mahayana Ch'an, Ch'an with Form and without Form, etc. But the Ch'an of the Ch'an School [of China] is the highest, the supreme Ch'an, different from all the others. This hall in which we are now sitting is called the Hall of Prajna, or the Arena of Enlightenment. It is here that you should penetrate into the 'sensation of doubt,' and cut off the root of life. In this hall only the teaching of Nothingness or the Dharma of Non-doing is studied. Because [in reality] there is nothing to be done and nothing to be gained, anything that is subject to action or doing is bound to have 'arising' and 'extinction' connected with it.

"Anything that is obtainable must also be losable. All other Dharma practices, such as prostrations, penitence, reciting sutras, etc., are all doing something; they are all, therefore, relative means and expedient teachings. Zen is to teach you to take up [the thing] right at this very moment without using any words at all. A monk asked Nan Chuan, 'What is Tao?' Nan Chuan answered, 'The ordinary mind is Tao.' Look! do you all understand this? In reality we have always been in the Tao – eating, walking, dressing, etc. No activity in which we are engaged can be separated from Tao. Our fault is that we cling to things all the time; thus we cannot realize that the self-mind is Buddha.

"A scholar, Ta Mei, asked Ma Tsu, 'What is Buddha?' Ma Tsu replied, 'The mind is Buddha.' As soon as he heard the answer Ta Mei became enlightened. He then bowed down to Ma Tsu, thanked him, and left. Later, Ta Mei resided in a hermitage somewhere in Che Chiang Province and had many disciples. His fame came to the ears of Ma Tsu. In order to make sure of the authenticity of his understanding, Ma Tsu sent a monk to his hermitage to investigate him. This monk was given the koan of 'Not Mind and Not Buddha' with which to test Ta Mei. When the monk arrived at the hermitage, Ta Mei asked him, 'Where did you, Revered Monk, come from?'

" 'I came from the great Master Ma.'

" 'What kind of Buddhism is he teaching now?'

" 'Oh, of late his Buddhism has been completely changed!'

" 'How did it change?'

" 'Formerly the great Master Ma always said, "The very mind is Buddha Itself," but now he says it is neither the mind nor the Buddha.'

"Ta Mei bit his lip and said, 'This old scoundrel is just trying to confuse people. Let him have [his] "neither the mind nor the Buddha." I still say the mind is Buddha!'

"From this story we know how the Zenists in the old days had their decisive and unshakable understandings, and how simply and directly they came to their Realization!

"Now you and I are very, very inferiorly endowed persons. Errant thoughts fill our minds to the brim. In their desperation, the great Patriarchs designed this Hua Tou practice for us, not because the Hua Tou is so wonderful in itself, but simply because the Patriarchs had no other way to help us except by devising such an expedient method.

"Master Kao Feng said, [4] 'When one practices Zen he should do so as though he were throwing a piece of tile into a deep pond; it sinks and sinks until it reaches the very bottom.' In other words, in our Tsen-Zen exercise we should look into the very bottom of the Hua Tou until we completely break through it. Master Kao Feng went further, and made a vow: 'If anyone takes up one Hua Tou without a second thought arising in seven days, and does not attain Enlightenment, I shall fall forever to the bottom of the Tongue-cutting Hell!'

[4. Kao Feng's Story: ch-2c5-story-kao-feng.htm ]

"When beginners first practice Zen, they always have difficulty in subduing their ever-flowing errant thoughts, and suffer the miseries of pains in their legs. They do not know how to work these matters out. The important thing is to stick to your Hua Tou at all times – when walking, lying, or standing – from morning to night observing the Hua Tou vividly and clearly, until it appears in your mind like the autumn moon reflected limpidly in quiet water. If you practice this way, you can be assured of reaching the state of Enlightenment. In meditation, if you feel sleepy, you may open your eyes widely and straighten your back; you will then feel fresher and more alert than before.

"When working on the Hua Tou, you should be neither too subtle nor too loose. If you are too subtle you may feel very serene and comfortable, but you are apt to lose the Hua Tou. The consequence will then be that you will fall into the 'dead emptiness.' Right in the state of serenity, if you do not lose the Hua Tou, you may then be able to progress further than the top of the hundred-foot pole you have already ascended. If you are too loose, too many errant thoughts will attack you. You will then find it difficult to subdue them. In short, the Zen practitioner should be well adjusted, neither too tight nor too loose; in the looseness there should be tightness, and in the tightness there should be looseness. Practicing in such a manner, one may then gain improvement, and merge stillness and motion into one whole.

"I remember in the old days when I practiced the circle-running exercise in Golden Mountain Monastery and other places, the supervising monks made us run like flying birds! Oh, we monks really could run! But when the warning board suddenly sounded its stop-signal, everybody stopped and stood still like so many dead poles! Now think! Under these circumstances, how could any drowsiness or distracting thoughts possibly arise?

"When you are meditating in the sitting posture, you should never bring the Hua Tou up too high; if you bring it up too much, you will get a headache. Nor should you place the Hua Tou in your chest; if you do, you will feel uncomfortable and suffer a pain there. Nor should you press the Hua Tou down too low; if you do, you will have trouble with your stomach and see delusive visions. What you should do is to watch the word 'Who,' softly and gently, with a smooth mind and calm, steady breath, like that of a hen as she hatches her egg or a cat when she watches a mouse. If you can do this well, you will find that one of these days your liferoot will suddenly and abruptly break off!"

The Fourth Day of the First Period, January 12th

"Now three days of the seven have already passed. I am glad you are all working so hard. Some of you have brought me some poems and stanzas you have composed and asked me to comment on them. Some of you say that you saw Voidness and light, and so on. Well, these are not bad things; but judging from them, I am sure that you must have forgotten all that I told you in the first two days. Last night I told you that to practice Tao is nothing more than to follow and to recognize the Way. What is the Way? To look into the Hua Tou which is like a royal sword. With it you kill the Buddha when Buddha comes, with it you slaughter the devil when the devil comes. Under this sword not a single idea is allowed to remain, not a solitary dharma is permitted to exist. How is it possible then to have so much distracted thought that you compose poems and stanzas, and see visions of light and Void? If you keep on doing this sort of thing, you will, in time, completely forget your Hua Tou. Now remember, to work on the Hua Tou is to look into it continuously without a single moment of interruption. Like the river ever flowing on, the mind should always be lucid and aware. All Sangsaric and Nirvanic ideas and conceptions should be wiped out! As the great Zen Master, Huang Po, said:

To practice the Tao

Is like defending the forbidden Royal Palace under invasion.

Guard it closely with your life,

And fight for it with all your mightl

Behold, if the freezing cold

Has not yet penetrated to the core of your bones,

How can it be possible for you

To smell the fresh fragrance of the blooming plum blossom?

"We sentient beings all have the Fundamental Consciousness, or the so-called Eighth Consciousness, which is comparable to the king of all consciousnesses. This king is surrounded by the Seventh, the Sixth, and all the other five consciousnesses – seeing, hearing, smelling, tasting, and touching. These are the five outer thieves. The Sixth Consciousness is the mind, the inner thief. The Seventh clings to the cognizant faculty of the Chief, or Eighth, Consciousness as its own great ego. Under its leadership the Sixth and the other five consciousnesses attach themselves to colors, sounds, touches, etc.; and thus the Chief Consciousness is entwined tightly by them and has no chance to turn its head around.

"The Hua Tou we are working on now is like a sharp sword with which we may slaughter all these harassing thieves and thus transform the Eighth Consciousness into the Wisdom of the Great Mirror, the Seventh Consciousness into the Wisdom of Equality, the Sixth into the Wisdom of Observation, and the five senses into the Wisdom of Performance. But the most important thing is to transform the Sixth and the Seventh Consciousnesses first, because it is these two faculties that take the lead and impose their influence on the rest. Their function is to distinguish, to differentiate, to conceptualize, and to fabricate. Now the poems and stanzas that you have composed, and the light and the Void, etc., that you have perceived, were all the fabrications of these two consciousnesses. You should forget all these things, and stick to your Hua Tou. Also you should know that there is another pitfall into which a Zen practitioner may easily fall, that is to meditate idly and make his mind deadly dull in utter torpidity. This is the worst error of all. Now let me tell you a koan:

"The Master who first established the Shih Tan Monastery, studied Zen under many different Masters, traveling from one place to another. He was a very industrious person, working on his Zen all the time. One night he stayed in an inn and heard a girl, who was a bean cake maker, singing the following song in an adjacent room while she was making bean cakes:

Oh, Chang is the bean cake,

And Lee is also the bean cake. [Endnote 2-6]

At night when you lay your head down upon your pillow,

A thousand thoughts may arise in your mind;

But when you awake in the morning,

You still continue to make the bean cakes.

"The Zen Master was absorbed in meditation when the girl sang this song. Upon hearing it, he suddenly awoke to Realization. From this story we know that Zen practice need not necessarily be carried out in the temples or meditation halls. Anywhere and everywhere one can reach Enlightenment if he can concentrate his mind on the work without being sidetracked by other things."

The Last Day of the Second Period, January 23

The Master addressed the attendant disciples as follows: "This is the last day of our two periods of Seven Days' Meditation. I congratulate you all on being able to complete the task. Today I shall investigate your Zen work and see whether you have gained any realization or improvement. You should stand up and, in plain and honest words, announce your understandings and experiences to all. Now, anyone who has become Enlightened, please stand up and say something!"

A long time passed, and no one stood up. The Master said nothing, and walked out of the Zen Hall.