SelfDefinition.Org

The Practice of Zen

Garma C.C. Chang

Chang Chen-chi (1920-1988)

4. Zen Master Meng Shan's Story

Esta página en español: ..historia-meng-shan.htm

When I was twenty years old I already knew of this matter [Zen]. [From that time on] until I was thirty-two, I studied with some eighteen elders to learn how actually to practice Zen. Nevertheless, I received no clear-cut teaching from them. Later I studied with the elder of Wan Shan, who taught me to observe the "Wu" word. In doing so he said that one should, in the twelve periods of a day, be ever alert like a cat waiting to catch a mouse, or like a hen intent on hatching an egg, never letting up on the task. Until one is fully and thoroughly enlightened, he should keep on working uninterruptedly, like a mouse gnawing at a coffin. If one can keep practicing in such a manner, in time he will definitely discover [the Truth]. Following these instructions, I meditated and contemplated diligently day and night for eighteen days. Then, while I was drinking a cup of tea, I suddenly understood the purport of Buddha's holding up the flower and of Mahakasyapa's smile to him. [1, 2] Delight overwhelmed me. I questioned three or four elders about my experience, but they said nothing. Several of the elders told me to identify my experience with the Ocean-seal Samadhi [Endnote 2-36] and to disregard all else. Their advice led me to an easy confidence in myself.

[1. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/

[2. The story about Mahakasyapa is now regarded as an invention. The earliest written record of it is dated 1077. Ref. Stuart Lachs, Zen Master in America, note 8.]

Two years after this, in the month of July during the Fifth Year of Chin Din [1264], I contracted dysentery at Chungking in Szechuan Province. My bowels moved a hundred times a day and brought me to the brink of death. All my former understanding became useless, and the so-called Ocean-seal Samadhi did not help me in the least. I had a body, but I could not move. I possessed a mouth, but I could not speak. I lay down, just waiting for death. All the Karmas and other fearful hallucinations appeared simultaneously before me. Frightened, puzzled, and lost, I felt crushed, annihilated under pressures and miseries.

With the thought of approaching death before me, I forced myself to make a will, and so disposed of all my worldly affairs. This accomplished, I slowly pulled myself up, burned a hill censer of incense, and seated myself steadily on a high seat. There I prayed silently to the Three Precious Ones and the Gods in the Heavens, repenting before them of all the sinful deeds I had committed in life. I then made my last petition: If my life is about to end, I wish through the power of Prajna and a sober state of mind that I may reincarnate in a favorable place, wherein I may become a monk at an early age. If by chance I recover from this sickness, I will renounce the world, become a monk, and strive to bring enlightenment to young Buddhists everywhere. Having made this vow, I then took up the "Wu" word and observed it inwardly. Before long my bowels rolled and twisted a number of times, but I ignored them. After I had sat for a long while, I felt my eyelids become fixed steadfastly. Again a long period of time elapsed in which I did not feel the presence of my body at all. There was nothing but the Hua Tou continuously presenting itself in my mind. It was not until night that I rose from my seat. I had half recovered from my illness. I sat again and meditated until after midnight. By then my recovery was complete. Both my body and my mind felt comfortable and light.

In August I went to Chiang Ning and joined the priesthood. There I remained in the monastery for one year; then I started my visiting journey. On this journey, I cooked my own food. Only then did I realize that the Zen task should be worked out at one stretch. It should never be interrupted.

Later I stayed at the Yellow Dragon Monastery. When I sat in meditation the first time I became drowsy, but I alerted myself and overcame it. I felt drowsy a second time, and alerted myself again to overcome it. When the drowsiness came for the third time, I felt very, very sleepy indeed. Then I got down and prostrated myself before Buddha, trying in different ways to pass the time. I returned to my seat again. With everything arranged, I decided to surmount my drowsiness once and for all. First I slept for a short while with a pillow, then with my head on my arm. Next I dozed without lying down. For two or three nights I struggled on in this way, feeling sleepy all day and evening. My feet seemed not to be standing on the ground, but floating in the air. Then suddenly the dark clouds before my eyes opened. My whole body felt comfortable and light as if I had just had a warm bath. Meanwhile the "doubt-sensation" in my mind became more and more intensified. Without effort it automatically and incessantly appeared before me. Neither sounds, views, nor desires and cravings could penetrate my mind. It was like the clear sky of autumn or like pure snow filling a silver cup. Then I thought to myself, "This is all very well, but no one here can give me advice or resolve these things for me." Whereupon I left the monastery and went to Che Chiang.

On the way I suffered great hardships, so that my work was retarded. On arrival I stayed with Master Ku Chan of Chin Tien, and made a vow that I would attain Enlightenment or never leave the monastery. After meditation for one month I regained the work lost on the journey; but meanwhile my whole body became covered with growing boils. These I ignored, and stressed my work, even to the point of disregarding my own life. In this way I could work better and gain more improvement. Thus I learned how to work in sickness.

One day I was invited out for dinner. On my way I took up the Hua Tou and worked at it, and thereby, without realizing it, I passed my host's house. Thus I learned how to keep up my work in activity. When I reached this state, the feeling was like the moon in the water – transparent and penetrating. Impossible to disperse or obliterate by rolling surges, it was inspiring, alive, and vivid all the time.

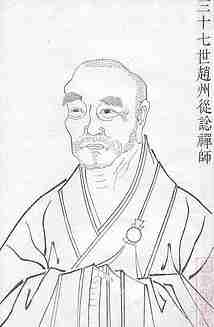

Chao Chou

On the sixth of March, while I was meditating on the "Wu" word, the Chief Monk came into the hall to burn incense. He struck the incense box, making some noise. Suddenly and abruptly I recognized myself, and caught and defeated Chao Chou. [Endnote 2-37] Whereupon I composed this stanza:

In despair I reached the dead end of the road;

I stamped upon the wave,

[But] it was only water.

Oh, that outstanding old Chao Chou,

His face is as plain as this!

In the autumn I saw Hsueh Yen at Ling An, as well as Tui Keng, Shih Keng, Hsu Chou, and other great elders. Hsu Chou advised me to consult Wan Shan, which I did. Wan Shan asked me: "Is not the saying, 'The glowing light shines serenely over the river sands,' a prosaic remark by that foolish scholar Chang?" I was just about to answer when Master Shan shouted at me, "Get out!" From that moment I was not interested in anything; I felt insipid and dull at all times, and in all activities.

Six months passed. One day in the spring of the next year I came back to the city from a journey. While climbing some stone steps I suddenly felt all the doubts and obstacles that were weighing me down melt away like thawing ice. I did not feel that I was walking the road with a physical body. Immediately, I went to see Master Shan. He asked me the same question that he had put before. In answer I just turned his bed upside down onto the ground. Thus, one by one, I understood some of the most obscure and misleading koans.

Friends, if you want to practice Zen, you must be extremely earnest and careful. If I had not caught dysentery in Chungking, I would probably have frittered my whole life away. The important thing is to meet the right teacher and to have a right view. This is why in olden times teachers were searched for in all possible ways, and their advice sought day and night. For only through this earnest approach may one clear away his doubts, and be assured of the authenticity of his Zen experience and understanding.