SelfDefinition.Org

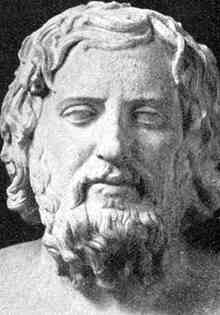

Hiero a.k.a Tyrannicus

by Xenophon

(430-354 BC)

Part 7

(1) When he heard these things from [Hiero], Simonides spoke. "Honor," he said "seems to be something great; and human beings undergo all toil and endure all danger striving for it.

(2) "You too, apparently, although tyranny has as many difficulties as you say, nevertheless rush into it headlong in order that you may be honored, and in order that all—all who are present—may serve you in all your commands without excuses, admire you, rise from their seats, give way in the streets, and always honor you both in speeches and deeds. For these are of course the kinds of things that subjects do for tyrants and for anyone else they happen to honor at the moment.

(3) "I myself think, Hiero, that a real man differs from the other animals in this striving for honor. Since, after all, all animals alike seem to take pleasure in food, drink, sleep, and sex. But ambition does not arise naturally either in the irrational animals or in all human beings. Those in whom love of honor and praise arises by nature differ the most from, and who are also believed to be no longer human beings merely, but real men.

(4) "Accordingly, it seems to me that you probably endure all these things you bear in the tyranny because you are honored above all other human beings. For no human pleasure seems to come closer to what is divine than the joy connected with honors."

(5) To this Hiero said, "But, Simonides, even the honors of the tyrants appear to me of a kind similar to that which I demonstrated their sexual pleasures to be.

(6) "For services from those who do not love in return we did not think to be favors, anymore than sex which is forced appears pleasant. In the same way, services from those under fear are not honors.

(7) "For must we say that those who are forced to rise from their chairs stand up to honor those who are treating them unjustly, or that those who give way in the streets to the stronger yield to honor those who are treating them unjustly?

(8) "And further, the many offer gifts to those they hate, and what is more, particularly when they fear they may suffer some harm from them. But this, I think, would probably be considered deeds of slavery. Whereas I believe for my part that honors derive from acts the opposite of this.

(9) "For when human beings, considering a real man able to be their benefactor, and believing that they enjoy his goods, for this reason have him on their lips in praise; when each one sees him as his own private good; when they willingly give way to him in the streets and rise from their chairs out of liking and not fear; when they crown him for his public virtue and beneficence, and willingly bestow gifts on him; these men who serve him in this way, I believe, honor him truly; and the one deemed worthy of these things I believe to be honored in reality. I myself count blessed the one so honored.

(10) "For I perceive that he is not plotted against, but rather that he causes anxiety lest he suffer harm, and that he lives his life—happy, without fear, without envy, and without danger. But the tyrant, Simonides, knows well, lives night and day as one condemned by all human beings to die for his injustice."

(11) When Simonides heard all this through to the end, he said, "But why, Hiero, if being a tyrant is so wretched, and you realize this, do you not rid yourself of so great an evil, and why did no one else ever willingly let a tyranny go, who once acquired it?"

(12) "Because," he said, "in this too is tyranny most miserable, Simonides: it is not possible to be rid of it either. For how would some tyrant ever be able to repay in full the money of those he has dispossessed, or suffer in turn the chains he has loaded on them, or how supply in requital enough lives to die for those he has put to death?

(13) "Rather, if it profit any man, Simonides, to hang himself, know," he said, "that I myself find this most profits the tyrant. He alone, whether he keeps his troubles or lays them aside, gains no advantage."