SelfDefinition.Org

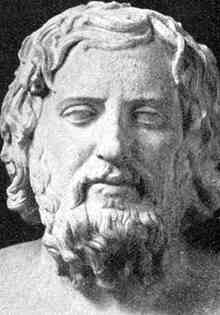

Hiero a.k.a Tyrannicus

by Xenophon

(430-354 BC)

Part 1

(1) Simonides the poet came once upon a time to Hiero the tyrant. After both had found leisure, Simonides said,

"Would you be willing, Hiero, to explain what you probably know better than I?"

"And just what sort are they," said Hiero, "which I myself would know better than so wise a man as you?"

(2) "I know for my part," he said, "that you have been a private man and are now a tyrant. It is likely, then, that since you have experienced both, you also know better than I how the tyrannical and the private life differ in human joys and pains."

(3) "Then why don't you remind me of the things in private life," said Hiero, "since, at present at least, you are still a private man? For in this way I think I would best be able to show you the difference in each."

(4) So Simonides spoke in this way: "Well then, Hiero, I seem to have observed that private men feel pleasure and distress at sights through the eyes; at sounds through the ears, at smells through the nose, at foods and drinks through the mouth, and as to sex through what, of course, we all know.

(5) "As to what is cold and hot, hard and soft, light and heavy, when we distinguish between them, we seem to me to be pleased and pained by them with our entire body. And we seem to me to enjoy and be pained by what is good and bad sometimes through the soul alone, and at other times through the soul and through the body.

(6) "That we are pleased by sleep I imagine I'm aware but how, by what, and when—of this I believe I am somehow more ignorant," he said. "And perhaps it is not to be wondered that things in waking give us clearer perceptions than do things in sleep."

(7) Now to this Hiero replied: "Then I for one, Simonides," he said, "would certainly be unable to say how the tyrant can perceive anything other than these things you yourself have mentioned. So that up to this point at least I do not know whether the tyrannical life differs in any respect from the private life."

(8) Simonides spoke. "But in this way it does differ," he said, "[the tyrant's] pleasure is multiplied many times over through each of these means, and he has the painful things for less.

"That is not so, Simonides," Hiero said. "Know well tyrants have much fewer pleasures than private men who live on modest means, and they have far more and greater pains."

(9) "What you say is incredible," said Simonides. "For if this were the case, why would many desire to be tyrant, and what's more many who are reputed to be most able men? And why would all be jealous of the tyrants?"

(10) "By Zeus," said Hiero, "because they speculate about it, although they are inexperienced in the deeds of both lives. I will try to teach you that I speak the truth, beginning with sight; for I seem to recall you also began speaking there.

(11) "In the first place, when I reason on it, I find that tyrants are at a disadvantage in the spectacles which impress us through vision. For one thing, there are different things in different countries worth seeing. Private men go to each of these places, and to whatever cities they please, for the sake of spectacles. And they go to the common festivals, where the things which human beings hold most worth seeing are brought together.

(12) "But tyrants have little share in viewing these, for it is not safe for them to go where they are not going to be stronger than those who will be present. Nor is what they possess at home secure enough for them to entrust it to others and go abroad. For there is the fear that they will at the same time be deprived of their rule and become powerless to take vengeance on those who have committed the injustice.

(13) "Perhaps, then, you may say, 'But after all [sights] of this kind come to them, even when they remain at home.' By Zeus, yes, Simonides, but only few of many; and these, being of such a kind, are sold to tyrants at such a price that those who display anything at all expect to leave, receiving from the tyrant in a moment an amount multiplied many times over what they acquire from all human beings besides in their entire lifetime."

(14) And Simonides said, "But if you are worse off with respect to spectacles, you at least gain the advantage through hearing; since you never lack praise, the sweetest sound. For all who are in your presence praise everything you say and everything you do. You in turn are out of the range of abuse, the harshest of things to hear; for no one is willing to accuse a tyrant to his face."

(15) Hiero spoke. "What pleasure," he said, "do you think a tyrant gets from those who say nothing bad, when he knows clearly every thought these silent men have is bad for him? Or what pleasure do you think he gets from those who praise him, when he suspects them of bestowing their praise for the sake of flattery?"

(16) And Simonides said, "By Zeus, this I certainly grant you, Hiero: the sweetest praise comes from those who are free in the highest degree. But, you see, you still would not persuade any human being that you do not get much more pleasure from that which nourishes us humans."

(17) "I know, at least, Simonides," he said, "that the majority judge we drink and eat with more pleasure than private men, believing they themselves would dine more pleasantly on the dish served to us than the one served to them; for what surpasses the ordinary causes the pleasures.

(18) "For this reason all human beings save tyrants anticipate feasts with delight. For [tyrants'] tables are always prepared for them in such abundance that they admit no possibility of increase at feasts. So, First in this pleasure of hope [tyrants] are worse off than private men."

(19) "Next," he said, "I know well that you too have experience of this, that the more someone is served with an amount beyond what is sufficient, the more quickly he is struck with satiety of eating. So in the duration of pleasure too, one who is served many dishes fares worse than those who live in a moderate way."

(20) "But, by Zeus," Simonides said, "for as long as the soul is attracted, is the time that those who are nourished by richer dishes have much more pleasure than those served cheaper fare."

(21) "Then do you think, Simonides," said Hiero, "that the man who gets the most pleasure from each act also has the most love for it?"

"Certainly," he said.

"Well, then, do you see tyrants going to their fare with any more pleasure than private men to theirs?"

"No, by Zeus," he said, "I certainly do not, but, as it would seem to many, even more sourly."

(22) "For why else," said Hiero, "do you see so many contrived dishes served to tyrants: sharp, bitter, sour, and the like?"

"Gertainly," Simonides said, "and they seem to me very unnatural for human beings."

(23) "Do you think these foods," said Hiero, "anything else but objects of desire to a soft and sick soul? Since I myself know well, and presumably you know too, that those who eat with pleasure need none of these sophistries."

(24) "Well, and what is more," said Simonides, "as for these expensive scents you anoint yourself with, I suppose those near you enjoy them more than you yourselves do; just as a man who has eaten does not himself perceive graceless odors as much as those near him."

(25) "Moreover," said Hiero, "so with respect to food, the one who always has all kinds takes none of it with longing. But the one who lacks something takes his fill with delight whenever it comes to sight before him."

(26) "It is probable that the enjoyment of sex," said Simonides, "comes dangerously close to producing desires for tyranny. For there it is possible for you to have intercourse with the fairest you see."

(27) "But now," said Hiero, "you have mentioned the very thing—know well—in which, if at all, we are at a greater disadvantage than private men. For as regards marriage, first there is marriage with those superior in wealth and power, which I presume is held to be the noblest, and to confer a certain pleasurable distinction on the bridegroom. Secondly, there is marriage with equals. But marriage with those who are lower is considered very dishonorable and useless.

(28) "Well then, unless the tyrant marries a foreign woman, necessity compels him to marry an inferior, so that what would content him is not readily accessible to him. Furthermore, it is attentions from the proudest women which give the most pleasure, whereas attentions from slaves, even when they are available, do not content at all, and rather occasion fits of terrible anger and pain if anything is neglected.

[Content advisory: Here the conversation turns to sex with boys. Such were the Greeks. If this bothers the reader, please skip to the next chapter. The topic is not repeated.]

(29) "But in the pleasures of sex with boys the tyrant comes off still much worse than in those with women for begetting offspring. For I presume we all know these pleasures of sex give much greater enjoyment when accompanied with love.

(30) "But love in turn is least of all willing to arise in the tyrant, for love takes pleasure in longing not for what is at hand, but for what is hoped for. Then, just as a man without experience of thirst would not enjoy drinking, so too the man without experience of love is without experience of the sweetest pleasures of sex." So Hiero spoke.

(31) Simonides laughed at this and said, "What do you mean, Hiero? So you deny that love of boys arises naturally in a tyrant? How could you, in that case, love Dailochus, the one they call the fairest?"

(32) "By Zeus, Simonides," he said, "it is not because I particularly desire to get what seems available in him, but to win what is very ill-suited for a tyrant.

(33) "Because I love Dailochus for that very thing which nature perhaps compels a human being to want from the fair, and it is this I love to win; but I desire very deeply to win it with love, and from one who is willing; and I think I desire less to take it from him by force than to do myself an injury.

(34) "I believe myself that to take from an unwilling enemy is the most pleasant of all things, but I think the favors are most pleasant from willing boys.

(35) "For instance, the glances of one who loves back are pleasant; the questions are pleasant and pleasant the answers; but fights and quarrels are the most sexually provocative.

(36) "It certainly seems to me," he said, "that pleasure taken from unwilling boys is more an act of robbery than of sex. Although the profit and vexation to his private enemy give certain pleasures to the robber, yet to take pleasure in the pain of whomever one loves, to kiss and be hated, to touch and be loathed—must this not by now be a distressing and pitiful affliction?

(37) "To the private man it is immediately a sign that the beloved grants favors from love when he renders some service, because the private man knows his beloved serves under no compulsion. But it is never possible for the tyrant to trust that he is loved.

(38) "For we know as a matter of course that those who serve through fear try by every means in their power to make themselves appear to be like friends by the services of friends.

"And what is more, plots against tyrants spring from none more than from those who pretend to love them most."