SelfDefinition.Org

The Zen Teaching of Huang Po

On the Transmission of Mind

The Chung-Ling Record & The Wan-Ling Record

Translated by John Blofeld

Wan Ling Record The Anecdotes

Esta página en español: ../b2-wan-ling-anecdotas.htm

Paragraphs 27 – 37 (of 56)

27

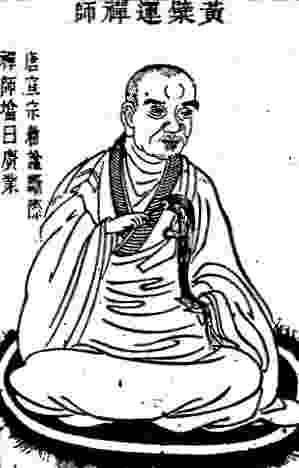

27. Our Master came originally from Fukien, but took his vows upon Mount Huang Po in this prefecture while he was still very young. [27a] In the centre of his forehead was a small lump shaped like a pearl. His voice was soft and agreeable, his character unassuming and placid.

Some years after his ordination, while journeying to Mount T'ien T'ai, he fell in with a monk with whom he soon came to feel like an old acquaintance; so they continued their journey together. Finding the way barred by a mountain stream in flood, our Master lent upon his staff and halted, at which his friend entreated him to proceed.

"You go first," said our Master. So the former floated his big straw rain-hat on the torrent and easily made his way to the other side. [27b]

"I," sighed the Master, "have allowed such a fellow to accompany me! I ought to have slain him with a blow of my staff!" [27c]

28

28. Once a certain monk, on taking leave of Master Kuei Tsung, was asked where he intended to go.

"I intend to visit all the places where the five kinds of Zen are taught," he replied.

"Oh," exclaimed Kuei Tsung. "Other places may have five kinds; here we have only the one kind."

But when the monk enquired what it was, he received a sudden blow. "I see, I see!" he shouted excitedly.

"Speak, speak!" roared Kuei Tsung. So the monk got ready to say something further, but just at that moment he received another blow.

Afterwards, this same monk arrived at our Master's monastery and, being asked by Huang Po where he had come from, explained that he had recently left Kuei Tsung.

"And what instructions did you receive from him?" enquired our Master, whereupon the monk related the above story.

During the next assembly, our Master took this anecdote for his text and said: "Master Ma [28a] really excels the Eighty-Four Deeply Enlightened Ones! The questions people ask are all of them no better than stinking muck saturating the ground. There is only Kuei Tsung who is worth something." [28b]

29

29. Our Master once attended an assembly at the Bureau of the Imperial Salt Commissioners at which the Emperor T'ai Chung was also present as a śramanera. [29a] The śramanera noticed our Master enter the hall of worship and make a triple prostration to the Buddha, whereupon he asked: "If we are to seek nothing from the Buddha, Dharma or Sangha, what does Your Reverence seek by such prostrations?"

"Though I seek not from the Buddha," replied our Master, "or from the Dharma, or from the Sangha, it is my custom to show respect in this way."

"But what purpose does it serve?" insisted the śramanera, whereupon he suddenly received a slap.

"Oh," he exclaimed. "How uncouth you are!"

"What is this?" cried the Master. "Imagine making a distinction between refined and uncouth!" So saying, he administered another slap, causing the śramanera to betake himself elsewhere! [29b]

30

30. During his travels, our Master paid a visit to Nan Ch'üan (his senior). One day at dinner-time, he took his bowl and seated himself opposite Nan Ch'üan's high chair. Noticing him there, Nan Ch'üan stepped down to receive him and asked: "How long has Your Reverence been following the Way?"

"Since before the era of Bhisma Rāja," came the reply. [30a]

"Indeed?" exclaimed Nan Ch'üan. "It seems that Master Ma [30b] has a worthy grandson [30c] here." Our Master then walked quietly away.

A few days later, when our Master was going out, Nan Ch'üan remarked: "You are a huge man, so why wear a hat of such ridiculous size?"

"Ah, well," replied our Master. "It contains vast numbers of chiliocosms."

"Well, what of me?' enquired Nan Ch'üan, but the Master put on his hat and walked off. [30d]

31

31. Another day, our Master was seated in the tea-room when Nan Ch'üan came down and asked him: "What is meant by "A clear insight into the Buddha-Nature results from the study of Dhyāna (mind control) and prajñ ā (wisdom)"?"

Our Master replied: "It means that, from morning till night, we should never rely on a single thing."

"But isn't that just Your Reverence's own concept of its meaning?

"How could I be so presumptuous?"

"Well, Your Reverence, some people might pay out cash for rice-water, but whom could you ask to give anything for a pair of home-made straw sandals like that?"

At this our Master remained silent.

Later, Wei Shan mentioned the incident to Yang Shan, enquiring if our Master's silence betokened defeat.

"Oh no!" answered Yang. "Surely you know that Huang Po has a tiger's cunning?"

"Indeed there's no limit to your profundity," exclaimed the other. [31]

32

32. Once our Master requested a short leave of absence and Nan Shan asked where he was going.

"I'm just off to gather some vegetables."

"What are you going to cut them with?"

Our Master held up his knife, whereupon Nan Shan remarked: "Well, that's all right for a guest but not for a host."

Our Master showed his appreciation with a triple prostration. [32]

33

33. One day, five new arrivals presented themselves to our Master in a group. One of them, instead of making the customary prostration, remained standing and greeted him somewhat casually with a motion of his clasped hands.

"And do you know how to be a good hunting-dog?" enquired our Master.

"I must follow the antelope's scent."

"Suppose it leaves no scent, what will you follow then?"

"Then I'd follow its hoof-marks."

"And if there were no hoof-marks, what then?"

"I could still follow the animal's tracks."

"But what if there were not even tracks? How would you follow it then?"

"In that case," said the newcomer, "it would surely be a dead antelope."

Our Master said nothing more at the time but, on the following morning after his sermon, he asked: "Will yesterday's antelope-hunting monk now step forward." The monk complied and our Master enquired: "Yesterday, my Reverend friend, you were left without anything to say. How was that?"

Finding that the other returned no answer, he continued: "Ah, you may call yourself a real monk, but you are just an amateur novice." [33]

34

34. Once, when our Master had just dismissed the first of the daily assemblies at the K'ai Yuan Monastery near Hung Chou, I [34a] happened to enter its precincts. Presently I noticed a wall-painting and, by questioning the monk in charge of the monastery's administration, learnt that it portrayed a certain famous monk.

"Indeed?" I said. "Yes, I can see his likeness before me, but where is the man himself?" My question was received in silence. [34b]

So I remarked: "But surely there ARE Zen monks here in this temple, aren't there?"

"Yes," replied the monastery administrator, "THERE IS ONE. [34c]

After that, I requested an audience with the Master and repeated to him my recent conversation.

"P'ei Hsiu!" cried the Master.

"Sir!" I answered respectfully.

"Where are YOU? "

Realizing that no reply was possible to such a question, I hastened to ask our Master to re-enter the hall and continue his sermon.

35

35. [35a] When the Master had taken his place in the assembly hall, he began:

"You people are just like drunkards. I don't know how you manage to keep on your feet in such a sodden condition. Why, everyone will die of laughing at you. It all seems so EASY, SO why do we have to live to see a day like this? Can't you understand that in the whole Empire of T'ang [35b] there are NO 'teachers skilled in Zen'?"

At this point, one of the monks present asked: "How can you say that? At this very moment, as all can see, we are sitting face to face with one who has appeared in the world [35c] to be a teacher of monks and a leader of men!"

"Please note that I did not say there is no ZEN," answered our Master. "I merely pointed out that there are no TEACHERS! "

Later, Wei Shan reported this conversation to Yang Shan and asked what it implied.

Said Yang Shan: "That swan is able to extract the pure milk from the adulterated mixture. It is very clear that he [35d] is not just an ordinary duck!"

"Ah," responded the other. "Yes, the point he made was very subtle." [35e]

36

36. One day I brought a statue of the Buddha and, kneeling respectfully before our Master, begged him to bestow upon me a sacred honorific.

"P'ei Hsiu!" he cried.

"Yes, Master?"

"How is it that you still concern yourself with names?"

All I could do was to prostrate myself in silence.

And there was another time when I offered our Master a poem I had written. He took it in his hands, but soon sat down and pushed it away. "Do you understand?" he asked.

"No, Master."

"But WHY don't you understand? Think a little! If things could be expressed like this with ink and paper, what would be the purpose of a sect like ours?"

My poem ran as follows:

When his Master bequeathed him Mind-Intuition,

He of great height with a pearl on his forehead

Dwelt for ten years by the river in Szech'uan.

Now, like a chalice borne by the waters,

He has come to rest on the banks of the Chang.

A thousand disciples follow behind him

With dragon-mien glorious, bearing the fragrance

Of flowers from afar. These are aspirant Buddhas,

Yet desiring to serve him humbly as pupils.

Who knows upon which the Transmission will fall?

Our Master later replied with another poem:

Mind is a mighty ocean, a sea which knows no bounds.

Words are but scarlet lotus to cure the lesser ills.

Though there be times of leisure when my hands both lie at rest,

"Tis not to welcome idlers that I raise them to my breast! [36]

37

37. Our Master said: Those who desire progress along the Way must first cast out the dross acquired through heterogeneous learning. Above all, they must avoid seeking for anything objective or permitting themselves any sort of attachment. Having listened to the profoundest doctrines, they must behave as though a light breeze had caressed their ears, a gust had passed away in the blink of an eye. By no means may they attempt to follow such doctrines. To act in accordance with these injunctions is to achieve profundity. The motionless contemplation of the Tathāgatas implies the Zen-mindedness of one who has left the round of birth and death forever. From the days when Bodhidharma first transmitted naught but the One Mind, there has been no other valid Dharma. Pointing to the identity of Mind and the Buddha, [37a] he demonstrated how the highest forms of Enlightenment could be transcended. Assuredly he left no other thought but this. If you wish to enter by the gate of our sect, this must be your only Dharma.

If you expect to gain anything from teachers of other doctrines, what is your purpose in coming here? So it is said that if you have the merest intention to indulge in conceptual thinking, behold, your very intention will place you in the clutch of demons. Similarly, a conscious lack of such intention, or even a consciousness that you do NOT have NO such intention, will be sufficient to deliver you into the demons' power. But they will not be demons from outside; they will be the self-creations of your own mind. The only reality is that "Bodhisattva" whose existence is totally un-manifested even in a spiritual sense – the Trackless One. If ever you should allow yourselves to believe in the more than purely transitory existence of phenomena, you will have fallen into a grave error known as the heretical belief in eternal life; but if, on the contrary, you take the intrinsic voidness of phenomena to imply mere emptiness, then you will have fallen into another error, the heresy of total extinction. [37b]

Thus, "the Triple World is only Mind; the myriad phenomena are only consciousness" is the sort of thing taught to people who previously maintained even falser views and suffered from even graver errors of perception. [37c] Similarly, the doctrine that the Dharmakāyā [37d] is something attained only after reaching full Enlightenment was merely intended as a means of converting the Theravādin saints from graver errors. Finding these mistaken views prevalent, Gautama Buddha refuted two sorts of misunderstanding – the notions that Enlightenment will lead to the perception of a universal substance, composed of particles which some hold to be gross and others subtle. [37e]

How is it possible that Gautama Buddha, who denied all such views as those I have mentioned, could have originated the present conceptions of Enlightenment? But, as these doctrines are still commonly taught, people become involved in the duality of longing for "light" and eschewing "darkness". In their anxiety to SEEK Enlightenment on the one hand and to ESCAPE from the passions and ignorance of corporeal existence on the other, they conceive of an Enlightened Buddha and unenlightened sentient beings as separate entities. Continued indulgence in such dualistic concepts as these will lead to your rebirth among the six orders of beings, life after life, aeon upon aeon, forever and forever! And why is it thus? Because of falsifying the doctrine that the original source of the Buddhas is that self-existent Nature. Let me assure you again that the Buddha dwells not in light, nor sentient beings in darkness, for the Truth allows no such distinctions. The Buddha is not mighty, nor sentient beings feeble, for the Truth allows no such distinctions. The Buddha is not Enlightened, nor sentient beings ignorant, for the Truth allows no such distinctions. It is all because you take it upon yourself to talk of EXPLAINING Zen!

As soon as the mouth is opened, evils spring forth. People either neglect the root and speak of the branches, or neglect the reality of the "illusory" world and speak only of Enlightenment. Or else they chatter of cosmic activities leading to transformations, while neglecting the Substance from which they spring – indeed, there is NEVER any profit in discussion.

Once more, ALL phenomena are basically without existence, though you cannot now say that they are NONEXISTENT. Karma having arisen does not thereby exist; karma destroyed does not thereby cease to exist. Even its root does not exist, for that root is no root. Moreover, Mind is not Mind, for whatever that term connotes is far from the reality it symbolizes. Form, too, is not really form. So if I now state that there are no phenomena and no Original Mind, you will begin to understand something of the intuitive Dharma silently conveyed to Mind with Mind. Since phenomena and no-phenomena are one, there is neither phenomena nor no-phenomena, and the only possible transmission is to Mind with Mind.

When a sudden flash of thought occurs in your mind and you recognize it for a dream or an illusion, then you can enter into the state reached by the Buddhas of the past – not that the Buddhas of the past really exist, or that the Buddhas of the future have not yet come into existence. Above all, have no longing to become a future Buddha; your sole concern should be, as thought succeeds thought, to avoid clinging to any of them. Nor may you entertain the least ambition to be a Buddha here and now. Even if a Buddha arises, do not think of him as "Enlightened" or "deluded", "good" or "evil". Hasten to rid yourself of any desire to cling to him. Cut him off in the twinkling of an eye! On no account seek to hold him fast, for a thousand locks could not stay him, nor a hundred thousand feet of rope bind him. This being so, valiantly strive to banish and annihilate him.

I will now make luminously clear how to set about being rid of that Buddha. Consider the sunlight. You may say it is near, yet if you follow it from world to world you will never catch it in your hands. Then you may describe it as far away and, lo, you will see it just before your eyes. Follow it and, behold, it escapes you; run from it and it follows you close. You can neither possess it nor have done with it. From this example you can understand how it is with the true Nature of all things and, henceforth, there will be no need to grieve or to worry about such things.

Now, beware of going on to say that my recommendation to cut off the Buddha was profane, or that my comparing him to the sunshine was pious, as though I had wavered from the one extreme to the other! Followers of the other sects would then agree with you, but our Zen Sect will not admit either the profanity of the first nor the pious quality of the second. Nor do we regard the first as Buddha-like, or the second as something to be expected only from ignorant sentient beings. [37f]

Thus all the visible universe is the Buddha; so are all sounds; hold fast to one principle and all the others are Identical. On seeing one thing, you see ALL. On perceiving any individual's mind, you are perceiving ALL Mind. Obtain a glimpse of one way and ALL ways are embraced in your vision, for there is nowhere at all which is devoid of the Way. When your glance falls upon a grain of dust, what you see is identical with all the vast world-systems with their great rivers and mighty hills. To gaze upon a drop of water is to behold the nature of all the waters of the universe. Moreover, in thus contemplating the totality of phenomena, you are contemplating the totality of Mind. All these phenomena are intrinsically void and yet this Mind with which they are identical is no mere nothingness. By this I mean that it does exist, but in a way too marvellous for us to comprehend. It is an existence which is no existence, a non-existence which is nevertheless existence. So this true Void does in some marvellous way "exist". [37g]

According to what has been said, we can encompass all the vast world-systems, though numberless as grains of sand, with our One Mind. Then, why talk of "inside" and "outside"? Honey having the invariable characteristic of sweetness, it follows that all honey is sweet. To speak of this honey as sweet and that honey as bitter would be nonsensical! How COULD it be so? Hence we say that the Void has no inside and outside. There is only the spontaneously existing Bhūtatathatā (Absolute). And, for this same reason, we say it has no centre. There is only the spontaneously existing Bhūtatathatā.

Thus, sentient beings ARE the Buddha. The Buddha is one with them. Both consist entirely of the one "substance". The phenomenal universe and Nirvāna, activity and motionless placidity – ALL are of the one "substance". So also are the worlds and with the state that transcends worlds. Yes, the beings passing through the six stages of existence, those who have undergone the four kinds of birth, all the vast world-systems with their mountains and river, the Bodhi-Nature and illusion – ALL of them are thus. By saying that they are all of one substance, we mean that their names and forms, their existence and nonexistence, are void. The great world-systems, uncountable as Gang ā 's sands, are in truth comprised in the one boundless void. Then where CAN there be Buddhas who deliver or sentient beings to be delivered? When the true nature of all things that "exist" is an identical Thusness, how CAN SUCH distinctions have any reality?

If you suppose that phenomena arise of themselves, you will fall into the heresy of regarding things as having a spontaneous existence of their own. On the other hand, if you accept the doctrine of AN ĀTMAN, the concept "AN ĀTMAN" may land you among the Theravādins. [37h]

You people seek to measure all within the void, foot by foot and inch by inch, I repeat to you that all phenomena are devoid of distinctions of form. Intrinsically they belong to that perfect tranquillity which lies beyond the transitory sphere of form-producing activities, so all of them are coexistent with space and one with reality. Since no bodies possess real form, we speak of phenomena as void; and, since Mind is formless, we speak of the nature of all things as void. Both are formless and both are termed void. Moreover, none of the numerous doctrines has any existence outside your original Mind. All this talk of Bodhi, Nirvāna, the Absolute, the Buddha-Nature, Mahāyāna, Theravada, Bodhisattvas and so on is like taking autumn leaves for gold. To use the symbol of the closed fist: when it is opened, all beings – both gods and men – will perceive there is not a single thing inside. Therefore is it written:

There's never been a single thing;

Then where's defiling dust to cling? [37i]

If "there's never been a single thing", past, present and future are meaningless. So those who seek the Way must enter it with the suddenness of a knife-thrust. Full understanding of this must come before they can enter. Hence, though Bodhidharma traversed many countries on his way from India to China, he encountered only one man, the Venerable Ko, to whom he could silently transmit the Mind-Seal, the Seal of your own REAL Mind. Phenomena are the Seal of Mind, just as the latter is the Seal of phenomena. Whatever Mind is, so also are phenomena – both are equally real and partake equally of the Dharma-Nature, which hangs in the void. He who receives an intuition of this truth has become a Buddha and attained to the Dharma. Let me repeat that Enlightenment cannot be bodily grasped (attained perceived, etc .), for the body is formless; nor mentally grasped (etc.), for the mind is formless; nor grasped (etc.), through its essential nature, since that nature is the Original Source of all things, the real Nature of all things, permanent Reality, of Buddha! How can you use the Buddha to grasp the Buddha, formlessness to grasp formlessness, mind to grasp mind, void to grasp void, the Way to grasp the Way? In reality, there is nothing to be grasped (perceived, attained, conceived, etc.) – even not-grasping cannot be grasped. So it is said: "There is NOTHING to be grasped." We simply teach you how to understand your original Mind.

Moreover, when the moment of understanding comes, do not think in terms of understanding, not understanding or not not-understanding, for none of these is something to be grasped. This Dharma of Thusness when "grasped" is "grasped", but he who "grasps" it is no more conscious of having done so than someone ignorant of it is conscious of his failure. Ah, this Dharma of Thusness – until now so few people have come to understand it that it is written: "In this world, how few are they who lose their egos!" As for those people who seek to grasp it through the application of some particular principle or by creating a special environment, or through some scripture, or doctrine, or age, or time, or name, or word, or through their six senses – how do they differ from wooden dolls? But if, unexpectedly, one man were to appear, one who formed no concept based on any name or form, I assure you that this man might be sought through world after world, always in vain! His uniqueness would assure him of succeeding to the Patriarch's place and earn for him the name of Śākya-muni's true spiritual son: the conflicting aggregates of his ego-self would have vanished, and he would indeed be the One! Therefore is it written: "When the King attains to Buddhahood, the princes accordingly leave their home to become monks. Hard is the meaning of this saying! It is to teach you to refrain from seeking Buddhahood, since any SEARCH is doomed to failure. Some madman shrieking on the mountain-top, on hearing the echo far below, may go to seek it in the valley. But, oh, how vain his search! Once in the valley, he shrieks again and straightway climbs to search among the peaks – why, he may spend a thousand rebirths or ten thousand aeons searching for the source of those sounds by following their echoes! How vainly will he breast the troubled waters of life and death! Far better that you make NO sound, for then will there be no echo – and thus it is with the dwellers in Nirvāna! No listening, no knowing, no sound, no track, no trace – make yourselves thus and you will be scarcely less than neighbours of Bodhidharma!

Continued next page: Wan Ling Anecdotes (cont)

Footnotes

Numbered by paragraph.

[27a] It was from this mountain that the Venerable Hsi Yün received the name by which he has been most commonly known until today.

[27b] Using it as a raft.

[27c] This anecdote seems to mean that the other monk was displaying one of the supranormal powers which Dhyāna-practice brings in its train but which should properly be regarded as mere by-products never to be used except in case of dire necessity. Huang Po was clearly disgusted with his companion for showing off.

[28a] Another name for Kuei Tsung.

[28b] Those familiar with Dr. Suzuki's books on Zen will not misinterpret Kuei Tsung's blows as being due to unnecessary crudeness or violence, nor Huang Po's strong language as being gratuitously rude. It seems that blows and strong language delivered at the right moment may induce SATORI, a flash of Enlightenment. The younger monk was in search of methods of withdrawal from the world by means of deep contemplation, and Kuei Tsung's first blow was intended as an antidote, for it implied: "The hand of bone and muscle which now causes you pain is as truly the Absolute as the mystic fervour you experience during contemplation." The second blow illustrated the folly of trying to express a sudden understanding of truth in words.

[29a] Here, probably, meaning a layman who had taken ten precepts instead of the normal five.

[29b] This story is, to anyone familiar with the customs of Eastern courts, hair-raising. That Huang Po should have dared to slap the Divine Emperor, the Son of Heaven, indicates both the immensity of the Master's personal prestige and the utter fearlessness which results logically from an unshakeable conviction that sams ā ric life is but a dream. The Emperor's willingness to accept the blow without retaliation indicates the depth of his admiration for the Master. It must be remembered that Huang Po, as one of several Masters belonging to a relatively small sect, with no temporal authority whatever, cannot be compared to a Western pope or archbishop who, under certain circumstances, might be able to strike a reigning emperor with impunity by reason of his authority as a Prince of the Church.

[30a] This implies that he had been upon the Way since many aeons before the present world cycle began – an allusion to the eternity in which we all share by reason of our identity with the One Mind.

[30b] Nan Ch'üan himself.

[30c] Spiritual descendant.

[30d] Just as the first part of the anecdote implies coexistence with eternity, so the second demonstrates coextensiveness with the Void. When the Master walks away, he implies that he has had the better of the argument. As will be seen, he acknowledges defeat with a triple prostration. Japanese commentators incline to the view that Huang Po's famous hat was too big even for him; but the Chinese, rightly I think, take it that the hat was much too small – which, of course, adds to the point of the story. The words of the text are "TAI KO HSIEH-TZÛ TA LI" – "wear one tiny-sized hat"; but the word TA, meaning "size" or "sized" also commonly means "big". Hence the error, which is more understandable inasmuch as HSIEH-TZÛ – "tiny" – is a highly colloquial Chinese term which probably means something quite different in Japanese. See beneath:

[31] Nan Ch'üan had made use of a term which was anathema to Huang Po – "concept". His silence was deeply significant; it implied that the Master NEVER indulged in concepts; and, perhaps, further, that "Your Reverence's" in the sense of "your" was also a term without validity. But it took a man of Yang Shan's calibre to penetrate through to his meaning.

[32] I find this anecdote hard to understand. Even the Zen Master Jên Wên, who experienced little difficulty in answering my other questions, remained silent over this one. So I am forced to venture my own guess, which is that the operative sentence means "Well, by all means use it, but don't let it use you", implying THAT ONLY CAUTIOUS AND TEMPORARY USE SHOULD BE MADE OF ANY EXTERNAL MEANS TO ENLIGHTENMENT. This, whether a good interpretation or not, is at any rate one of Huang Po's most firmly held opinions.

[33] Huang Po's opening remark implies that he was ready to accord the newcomer the equality tacitly demanded by his casual manner of greeting, PROVIDED he showed himself worthy. It was not until the other had displayed his ignorance of Zen that the Master decided upon a reproof in public. The antelope, of course, symbolizes the One Mind which, being utterly devoid of attributes, "leaves no tracks". A dead antelope would imply a state of extinction.

[34a] P'ei Hsiu.

[34b] Silence indicating that the man was neither anywhere nor nowhere; the first, because his real "Self" was no special entity; the second, because his ephemeral "self" undoubtedly occupied a point in space.

[34c] This profound reply has a double meaning – "one" in the sense of Huang Po, and "One"!

[35a] A continuation of [anecdote] 34.

[35b] China.

[35c] A phrase normally used of Buddhas.

[35d] Huang Po.

[35e] The implications of this anecdote are manifold. Huang Po's final remark implies among other things the impossibility of TEACHING Zen, which can only be properly apprehended through intuitive understanding arising from within ourselves. Another implication, harking back to the silence of the monastery administrator, is that the existence of INDIVIDUALS, Zen Masters or otherwise, is of a purely transitory order. Absorption in Zen leads to an experience of unity in which "one" and "other" are no longer valid. The One is neither a Zen Master nor anything else.

[36] Huang Po's poem implies that the Transmission can fall only upon one who has received intuitive experience leading to a direct perception of the One Mind. Mere intellectual brilliance will avail nothing. Hence, to those who idle away their time in metaphysical or intellectual discussions, the Master will make no sign.

[37a] Absolute.

[37b] Since we are compounded, in truth, wholely of eternal Mind, the notion of a permanent individual soul and that of total extinction are equally false.

[37c] In Huang Po's time there was a sect called the Wei Shih Tsung which held that, though nothing exists outside consciousness, the latter is in some sense a substance and therefore "real".

[37d] The body of the Absolute.

[37e] These views, which the Buddha is said to have refuted, would seem to be similar to the new scientific theory that the stuff of the universe is mind-stuff. This theory bears a certain superficial resemblance to Huang Po's doctrine; yet, though it is doubtless an advance on the materialistic conception of the last century, it stops far short of the truth as understood in Zen.

[37f] The whole of this passage is a warning against one of the most difficult types of dualism for a Buddhist to avoid – the dualism involved in conceiving of the Buddha or Nirvāna as separate from ourselves and saṁsāra. An attempt to blot out the Buddha is no more impious than the attempt to murder a stone image, since both are impervious to such designs.

[37g] This passage emphasizes the perfect identity of Nirvāna's matchless calm with the restless flux of the phenomenal universe.

[37h] The doctrine of ANĀTMAN has always been the centre of Buddhist controversy. There is no doubt that Gautama Buddha made it one of the central points of his teaching, but the interpretations of it are various. The Theravādins interpret it not only as "no self", but also as "no Self", thereby denying man both an ego and all participation in something of the nature of Universal Spirit or the One Mind. The Mahāyānists accept the interpretation of "egolessness", holding that the real "Self" is none other than that indescribable "non-entity", the One Mind; something far less of an "entity" than the ĀTMAN of the Brahmins. Coomaraswamy, for example, interprets the famous precept "Take the self as your only refuge" not by the Theravādin "Place no reliance upon intermediaries", but by "Take only the Self as your refuge", the "Self" meaning the same as the One Mind. If the Theravādins are right with their "No ego AND no Self", what is it that reincarnates and finally enters Nirvāna? And why do they take such pains to store up merit for future lives? For if the temporarily adhering aggregates of personality are not held together either by an ego-soul or by a Universal Self or the One Mind, whatever enters Nirvāna when those aggregates have finally dispersed can be of no interest to the man who devotes successive lives to attaining that goal. It is also difficult to understand how Buddhism could have swept like a flame across Asia if, at the time of its vast expansion, it had only the cold comfort of the present Theravādin interpretation of AN ĀTMAN to offer those in search of a religion by which to live. Zen adepts, like their fellow Mahāyānists, take ANĀTMAN to imply "no entity to be termed an ego, naught but the One Mind, which comprises all things and gives them their only reality."

[37i] It is recorded in the Sūtra of Hui Nêng,* or Wei Lang, that a certain monk likened Mind to a mirror which must be cleansed of the defilements of delusion and passion, thereby involving himself in a duality between the transitory and the real. The two lines just quoted are from Hui Nêng's reply, in which the duality is confuted. * See /zen/hui-neng/

Continued next page: Wan Ling Anecdotes (cont)