SelfDefinition.Org

The Zen Teaching of Huang Po

On the Transmission of Mind

The Chung-Ling Record & The Wan-Ling Record

Translated by John Blofeld

Translator's Introduction

Esta página en español: ../introduccion-blofeld.htm

About the Text

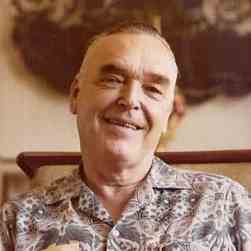

John Blofeld (1913-1987) Wikipedia Alchetron.Com

The present volume is a complete translation of the Huang Po Ch'uan Hsin Fa Yao, a ninth-century Chinese Buddhist text, much of which now appears in English for the first time. It contains a concise account of the sublime teachings of a great Master of the Dhyāna Sect, to which, in accordance with current Western practice, I shall henceforth refer by its Japanese name of Zen. Zen is often regarded as a uniquely Far Eastern development of Buddhism, but Zen followers claim that their Doctrine stems directly from Gautama Buddha himself. This text, which is one of the principle Zen works, follows closely the teachings proclaimed in the Diamond Sūtra or Jewel of Transcendental Wisdom, which has been ably translated by Arnold Price and published by the Buddhist Society, London. It is also close in spirit to The Sūtra of Wei Lang (Hui Nêng), another of the Buddhist Society's publications. But I have been deeply struck by the astonishing similarity to our text in spirit and terminology of the not-so-Far Eastern, eighth-century Tibetan Book of the Great Liberation, edited by Evans-Wentz and published by the Oxford University Press. In my opinion, these four books are among the most brilliant expositions of the highest Wisdom which have so far appeared in our language; and, of them all, the present text and the Tibetan Book of the Great Liberation present the Doctrine in a form best suited to the needs of Western readers.

The Place of this Text in Buddhism

Zen is a branch of the great Mahāyāna School prevailing in China and the more northerly countries of Eastern Asia, so its teachings are not accepted as orthodox Buddhism by followers of Hīnayāna or the Southern School. However, Western scholars are no longer unanimous in regarding Hīnayāna as being the sole guardian of the truths proclaimed by Buddhism's illustrious Founder, despite the early date of Hīnayāna's principal texts. The division into two schools took place some two thousand years ago in Northern India, since when Mahāyānists have accepted the teachings of the sister school as PART of the true Doctrine; though the latter, with less tolerance, repudiates whatever doctrines are specifically Mahāyāna. Zen, which appeared in the open much later, submits that, while all Buddhist sects present the truth in varying degrees, Zen alone preserves the very highest teachings of all – teachings based on a mysterious transmission of Mind which took place between Gautama Buddha and MahāKāsyapa, the only one of his disciples capable of receiving this transmission. Opinions as to the truth of this story naturally vary, but Masters like Huang Po obviously speak from some deep inner experience. He and his followers were concerned solely with a direct perception of truth and cannot have been even faintly interested in arguments about the historical orthodoxy of their beliefs. The great mystics of the world, such as Plotinus and Ekhart, who have plumbed the depths of consciousness and come face to face with the Inner Light, the all-pervading Silence, are so close to being unanimous concerning their experience of Reality that I, personally, am left in no doubt as to the truth of their accounts. Huang Po, in his more nearly everyday language, is clearly describing the same experience as theirs, and I assume that Gautama Buddha's mystical Enlightenment beneath the Bo Tree did not differ from theirs, unless PERHAPS in intensity and in its utter completeness. Could one suppose otherwise, one would have to accept several forms of absolute truth! Or else one would be driven to believe that some or all of these Masters were lost in clouds of self-deception. So, however slender the evidence for Zen's claim to have been founded by Gautama Buddha himself, I do not for one moment doubt that Huang Po was expressing in his own way the same experience of Eternal Truth which Gautama Buddha and others, Buddhist and non-Buddhist, have expressed in theirs. Moreover, since first embarking on the translation of this text, I have been astonished by its very close similarity to the teaching contained in the Tibetan Book of the Great Liberation which is attributed to the Lotus-Born Padma Sambhava. Since both are approximately of the same date, I suppose they COULD have derived from the same literary or oral source, but it seems much more probable that the two texts embody two different people's intimate perceptions of eternal truth. However, there are many who regard things otherwise and, in any case, it is proper for me to give some account of the traditional origin of Zen and of the modern theories concerning it.

The Origin, Growth and Expansion of Zen (Dhyāna) Buddhism

Traditional Origin

Gautama Buddha is said to have modified the exposition of his Doctrine to suit the different capacities of his various disciples and of those others who listened to his discourses. Once, at the end of a sermon, he picked a flower and held it up for the assembled monks to see. MahāKāsyapa, who alone understood the profound meaning of this gesture, responded with a smile. Later the Buddha called this disciple to him in private and mystically transmitted to him the wordless doctrine, or "with Mind transmitted Mind". MahāKāsyapa, in his turn, mystically transmitted the Doctrine to Ānanda, who thus became second in the line of twenty-eight Indian Patriarchs. The last of these was Bodhidharma, who travelled to China in the sixth century A.D. Here he became the First of the Chinese Patriarchs, who continued the transmission down to Hui Nêng (Wei Lang), the Sixth and last. Divisions within the sect followed and no more Patriarchs were created.

Theories Concerning the Origin and Development of the Sect

Buddhism, officially introduced into China in A.D. 61, probably reached the coast of Shantung as early as the first or second century B.C. Hīnayāna did not survive there for long, but Mahāyāna flourished exceedingly; various sects of Indian origin were developed and new sects created. One of the latest sects to appear was Zen, which rapidly attained great influence. Though an Indian origin was claimed for it, many people have doubted the truth of this; and some have gone so far as to doubt the existence of Bodhidharma himself. If, as I prefer to think, there was really such a person, he probably came to China from South India by way of Canton and visited the rulers of two Chinese states – for China was then divided, as so often in her long history.

Professor Daisetz Suzuki accepts the existence of Bodhidharma, but suggests that his teachings were derived from the La kāvatāra Sūtra, which appears to contain the germs of the wordless doctrine. Dr. Hu Shih [1] accepts neither the historical reality of Bodhidharma nor the authenticity of the earlier Zen works, regarding even the famous Sūtra of Hui Nêng (Wei Lang), the Sixth Patriarch, as a forgery of later date. To support his contentions, he adduces several eighth-century manuscripts discovered fairly recently in the Tun Huang caves, which differ both in name and substance from the traditionally accepted works of the Zen Masters. Dr. Hu Shih even describes Zen as a Chinese revolt against Buddhism – regarded as an alien doctrine from India.

[1. en.wikipedia.org/

I do not see that Zen sets itself up in opposition to other forms of Buddhism, including those whose Indian origin is more certain; for all sects regard Dhyāna-practice as an important means towards Enlightenment, i.e. the practice of turning the mind towards and striving to pierce the veils of sensory perception and conceptual thought in order to arrive at an intuitive perception of reality. Zen does, however, emphasize this to the exclusion or near-exclusion of much else, and it also differs from most other sects in regarding Enlightenment as a process which finally occurs in less time than it takes to blink an eye. Thus it is a form of Buddhism suited to those who prefer inward contemplation to the study of scriptures or to the performance of good works. Yet Zen is not unique in giving special emphasis to one particular aspect of the whole doctrine – if no one did that, there would be no sects. Moreover, Right Meditation (SAMMĀSAMĀDHI) forms the final step of the Noble Eightfold Path, which is accepted as the very foundation of Buddhism by Mahāyānists and Hīnayānists alike – and dhyāna-practice is aimed precisely at accomplishing that.

Hence, though there is very little evidence to prove or disprove the Indian origin of Zen, it does not seem to me especially unlikely that Bodhidharma did in fact arrive in China, bringing with him a doctrine of great antiquity inherited from his own teachers, a doctrine which infers that the seven preceding steps of the Noble Eightfold Path are to be regarded as preparation for the Eighth. And, if the Eighth is not held to be the outcome of the other Seven, it is difficult to understand why terms like "Path" and "steps" were employed.

The late Venerable T'ai Hsü, exemplifying a proper Buddhist attitude of broad tolerance, once described the various sects as so many beads strung on a single rosary. Mahāyāna Buddhists are encouraged to think for themselves and are free to choose whichever path best suits their individual requirements; the sectarian bitterness of the West is unknown in China. As the Chinese, though seldom puritanical, have generally been an abstemious people, sects chiefly emphasizing the strict observance of moral precepts – as does Hīnayāna – have seldom appealed to them, which may be one of the main reasons why the Southern School of Buddhism failed to take permanent root in China. Furthermore, Chinese intellectuals have since ancient times inclined to mild scepticism; to these people, Zen's austere "simplicity" and virtual lack of ritualism must have made a strong appeal. In another way, too, the ground in China had been well prepared for Zen. On the one hand, centuries of Confucianism had predisposed scholars against the fine-spun metaphysical speculation in which Indian Buddhists have indulged with so much enthusiasm; on the other, the teaching of Lao Tzû, Chuang Tzû, the Taoist sages, had to a great extent anticipated Zen quietism and prepared the Chinese mind for the reception of a doctrine in many ways strikingly similar to their own. (For somewhat similar reasons, Zen has begun to appeal to those people in the West who are torn between the modern tradition of scepticism and the need for a profound doctrine which will give meaning to their existence.)

So it may be that the historical authenticity of Zen is of relatively little importance, except to a limited number of scholars. It will certainly not seem of much importance to those who see in the teachings of the Zen Masters a brilliant reflection of some valid inner realization of Truth. Zen has long flourished in China and Japan and is now beginning to develop in the West, because those who have put its teachings to a prolonged practical test have discovered that they satisfy certain deep spiritual needs.

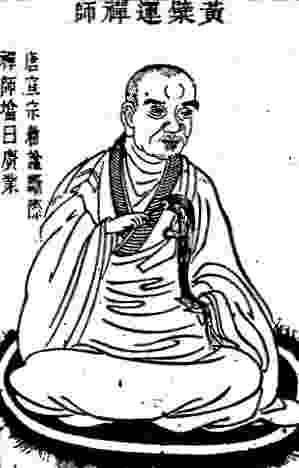

The Zen Master Huang Po

When Hui Nêng (Wei Lang), the Sixth Patriarch, received the transmission from Mind to Mind, the Zen Sect had already split into two branches. The Northern Branch, which taught that the process of Enlightenment is gradual, flourished for a while under imperial patronage, but did not long survive. Meanwhile, the Southern Branch, with its doctrine of Sudden Enlightenment, continued to expand and, later, to subdivide. The most important of the Sixth Patriarch's successors was Ma Tsu (Tao I) who died in A.D. 788. Huang Po, variously regarded as one or two generations junior to him, seems to have died as late as 850, after transmitting the Wordless Doctrine to I Hsüan, the founder of the great Lin Chi (Rinzai) Sect which still continues in China and flourishes widely in Japan. So Huang Po is in some sense regarded as the founder of this great Branch. Like all Chinese monks, he had several names, being known in his lifetime as Master Hsi Yün and as Master T'uan Chi; his posthumous name is taken from that of Mount Huang Po where he resided for many years. In Japan he is generally known as Obaku, which is the Japanese way of pronouncing the Chinese characters for Huang Po.

The Doctrine of Zen

Zen is already a familiar doctrine to many Western people, thanks to the comprehensive and illuminating works of Dr. Daisetz Tairo Suzuki, and to books by Western scholars, such as Mr. Christmas Humphreys' delightful Zen Buddhism. At first sight Zen works must seem so paradoxical as to bewilder the reader. On one page we are told that everything is indivisibly one Mind, on another that the moon is very much a moon and a tree indubitably a tree. Yet it is clear that this is not paradox for the sake of entertainment, for there are several million people who regard Zen as the most serious thing in life.

All Buddhists take Gautama Buddha's Enlightenment as their starting point and endeavour to attain to that transcendental knowledge that will bring them face to face with Reality, thereby delivering them from rebirth into the space-time realm forever. Zen followers go further. They are not content to pursue Enlightenment through aeons of varied existences inevitably bound up with pain and ignorance, approaching with infinite slowness the Supreme Experience which Christian mystics have described as "union with the Godhead". They believe in the possibility of attaining Full Enlightenment both here and now through determined efforts to rise beyond conceptual thought and to grasp that Intuitive Knowledge which is the central fact of Enlightenment. Furthermore, they insist that the experience is both sudden and complete. While the striving may require years, the reward manifests itself in a flash. But to attain this reward, the practice of virtue and dispassion is insufficient. It is necessary to rise above such relative concepts as good and evil, sought and found, Enlightened and unenlightened, and all the rest.

To make this point clearer, let us consider some Christian ideas of God. God is regarded as the First Principle, uncaused and unbegat, which logically implies perfection; such a being cannot be discovered through the relativity of time and space. Then comes the concept "God is good" which, as Christian mystics have pointed out, detracts from His perfection; for to be good implies not being evil – a limitation which inevitably destroys the unity and wholeness inseparable from perfection. This, of course, is not intended to imply that "God is evil", or that "God is both good and evil". To a mystic, He is none of these things, for He transcends them all. Again, the idea of God as the creator of the universe suggests a dualism, a distinction between creator and created. This, if valid, places God on a lower level than perfection, for there can be neither unity nor wholeness where A excludes B or B excludes A.

Zen followers (who have much in common with mystics of other faiths) do not use the term "God", being wary of its dualistic and anthropomorphic implications. They prefer to talk of "the Absolute" or "the One Mind", for which they employ many synonyms according to the aspect to be emphasized in relation to something finite. Thus, the word "Buddha" is used as a synonym for the Absolute as well as in the sense of Gautama, the Enlightened One, for it is held that the two are identical. A Buddha's Enlightenment denotes an intuitive realization of his unity with the Absolute from which, after the death of his body, nothing remains to divide him even in appearance. Of the Absolute nothing whatever can be postulated; to say that it exists excludes non-existence; to say that it does not exist excludes existence. Furthermore, Zen followers hold that the Absolute, or union with the Absolute, is not something to be attained; one does not ENTER Nirvāna, for entrance to a place one has never left is impossible. The experience commonly called "entering Nirvāna" is, in fact, an intuitive realization of that Self-nature which is the true Nature of all things. The Absolute, or Reality, is regarded as having for sentient beings two aspects. The only aspect perceptible to the unenlightened is the one in which individual phenomena have a separate though purely transitory existence within the limits of space-time. The other aspect is spaceless and timeless; moreover all opposites, all distinctions and "entities" of every kind, are here seen to be One. Yet neither is this second aspect, alone, the highest fruit of Enlightenment, as many contemplatives suppose; it is only when both aspects are perceived and reconciled that the beholder may be regarded as truly Enlightened. Yet, from that moment, he ceases to be the beholder, for he is conscious of no division between beholding and beheld. This leads to further paradoxes, unless the use of words is abandoned altogether. It is incorrect to employ such mystical terminology as "I dwell in the Absolute", "The Absolute dwells in me", or "I am penetrated by the Absolute", etc.; for, when space is transcended, the concepts of whole and part are no longer valid; the part is the whole – I AM the Absolute, except that I am no longer "I". What I behold then is my real Self, which is the true nature of all things; see-er and seen are one and the same, yet there is no seeing, just as the eye cannot behold itself.

The single aim of the true Zen follower is so to train his mind that all thought-processes based on the dualism inseparable from "ordinary" life are transcended, their place being taken by that Intuitive Knowledge which, for the first time, reveals to a man what he really is. If All is One, then knowledge of a being's true self-nature – his original Self – is equally a knowledge of all-nature, the nature of everything in the universe. Those who have actually achieved this tremendous experience, whether as Christians, Buddhists or members of other faiths, are agreed as to the impossibility of communicating it in words. They may employ words to point the way to others, but, until the latter have achieved the experience for themselves, they can have but the merest glimmer of the truth – a poor intellectual concept of something lying infinitely beyond the highest point ever reached by the human intellect.

It will now be clear that Zen Masters do not employ paradoxes from a love of cheap mystification, though they do occasionally make humorous use of them when humour seems needed. Usually, it is the utter impossibility of describing the Supreme Experience which explains the paradoxical nature of their speech. To affirm or deny is to limit; to limit is to shut out the light of truth; but, as words of some sort must be used in order to set disciples on to the right path, there naturally arises a series of paradoxes – sometimes of paradox within paradox within paradox.

It should perhaps be added that Huang Po's frequent criticisms of those Buddhists who follow the more conventional path, cultivating knowledge, good works and a compassionate heart through successive stages of existence, are not intended to call into question the value to humanity of such excellent practices. As a Buddhist, Huang Po must certainly have regarded these things as necessary for our proper conduct in daily life; indeed, we are told by P'ei Hsiu that his way of life was exalted; but he was concerned lest concepts such as virtue should lead people into dualism, and lest they should hold Enlightenment to be a gradual process attainable by other means than intuitive insight.

Huang Po's Use of the term "The One Mind"

The text indicates that Huang Po was not entirely satisfied with his choice of the word "Mind" to symbolize the inexpressible Reality beyond the reach of conceptual thought, for he more than once explains that the One Mind is not really MIND at all. But he had to use some term or other, and "Mind" had often been used by his predecessors. As Mind conveys intangibility, it no doubt seemed to him a good choice, especially as the use of this term helps to make it clear that the part of a man usually regarded as an individual entity inhabiting his body is, in fact, not his property at all, but common to him and to everybody and everything else. (It must be remembered that, in Chinese, "hsin" means not only "mind", but "heart" and, in some senses at least, "spirit" or "soul" – in short, the so-called REAL man, the inhabitant of the body-house.) If we prefer to substitute the word "Absolute", which Huang Po occasionally uses himself, we must take care not to read into the text any preconceived notions as to the nature of the Absolute. And, of course, "the One Mind" is no less misleading, unless we abandon all preconceived ideas, as Huang Po intended.

In an earlier translation of the first part of this book, I ventured to substitute "Universal Mind" for "the One Mind", hoping that the meaning would be clearer. However, various critics objected to this, and I have come to see that my term is liable to a different sort of misunderstanding; it is therefore no improvement on "the One Mind", which at least has the merit of being a literal translation.

Dhyāna-Practice

The book tells us very little about the practice of what, for want of a better translation, is often called meditation or contemplation. Unfortunately both these words are misleading as they imply some object of meditation or of contemplation; and, if objectlessness be stipulated, then they may well be taken to lead to a blank or sleeplike trance, which is not at all the goal of Zen. Huang Po seems to have assumed that his audience knew something about this practice – as most keen Buddhists do, of course. He gives few instructions as to how to "meditate", but he does tell us what to avoid. If, conceiving of the phenomenal world as illusion, we try to shut it out, we make a false distinction between the "real" and the "unreal". So we must not shut anything out, but try to reach the point where all distinctions are seen to be void, where nothing is seen as desirable or undesirable, existing or not existing. Yet this does not mean that we should make our minds blank, for then we should be no better than blocks of wood or lumps of stone; moreover, if we remained in this state, we should not be able to deal with the circumstances of daily life or be capable of observing the Zen precept: "When hungry, eat." Rather, we must cultivate dispassion, realizing that none of the attractive or unattractive attributes of things have any absolute existence.

Enlightenment, when it comes, will come in a flash. There can be no gradual, no partial, Enlightenment. The highly trained and zealous adept may be said to have prepared himself for Enlightenment, but by no means can he be regarded as partially Enlightened – just as a drop of water may get hotter and hotter and then, suddenly, boil; at no stage is it partly boiling, and, until the very moment of boiling, no qualitative change has occurred. In effect, however, we may go through three stages – two of non-Enlightenment and one of Enlightenment. To the great majority of people, the moon is the moon and the trees are trees. The next stage (not really higher than the first) is to perceive that moon and trees are not at all what they seem to be, since "all is the One Mind". When this stage is achieved, we have the concept of a vast uniformity in which all distinctions are void; and, to some adepts, this concept may come as an actual perception, as "real" to them as were the moon and the trees before. It is said that, when Enlightenment really comes, the moon is again very much the moon and the trees exactly trees; but with a difference, for the Enlightened man is capable of perceiving both unity and multiplicity without the least contradiction between them!

Huang Po's Attitude Towards Other Schools and Sects of Buddhism

As this book is likely to be read by many Buddhists who belong to the Theravādin (Hīnayāna School) or to Mahāyāna sects other than Zen, some explanation is needed here to forestall possible misunderstandings. A casual glance at our text or at some other Zen works might well give the impression that non-Zen Buddhism is treated too lightly. It should be remembered that Huang Po was talking principally to people who were already firm and serious-minded Buddhists. He tells us himself that nothing written down should be understood out of its context or without regard to the circumstances under which the recorded sermon was given. I feel that had he been speaking to non-Buddhists, his references to the "Three Vehicles" would have been couched in different language. A careful study of this work has persuaded me that Huang Po felt no desire to belittle the virtuel of those Buddhists who disagreed with his methods, but he did feel strongly that the Zen method is productive of the fastest results. He was much concerned to show that scripture-study and the performance of good works cannot lead to Enlightenment, unless the concept-forming processes of the finite mind are brought, properly, under control. As for good works and right living, we learn from P'ei Hsiu and others that his own way of life was exalted, but he had constantly to combat the notion that good works in themselves can bring us nearer to Enlightenment. Moreover, when the time has come for a Buddhist to discipline his mind so as to rise above duality, he enters a stage where the notions of both good and evil must be transcended like any other form of dualism. The Master was aware that many of the Buddhists he was preaching to had probably fallen into the all-too-common error of performing good works with a conscious desire to store up merit for themselves – a desire which is a form of attachment as inimical to Enlightenment as any other form of attachment. (The translator knows of several "sincere" Buddhists who lead lives very far from noble and who indulge sometimes in actions destructive of the happiness of others, but who firmly believe that their regular offerings to the Sangha and their periodic attendance at temple services will build up enough good karma to cancel out the results of their folly and their uncharitableness to others!)

As to the study of Sūtras and written works of all kinds on Buddhism, Huang Po must surely have assumed that most of the people who had taken the trouble to come to his mountain retreat for instruction were already fully conversant with Buddhist doctrine, and that what they lacked was the knowledge of mind-control. It is clear from his own words that he realized the necessity of books and teachings of various kinds for people less advanced. Unless a man is first attracted to Mysticism by the written doctrines delivered by the Lord Buddha or by other great teachers, he is most unlikely to see the necessity for mind-control, the central object of Huang Po's own teaching. Hence the Doctrine of Words must inevitably precede the Wordless Doctrine, except in certain rare cases. I am convinced that Huang Po had no intention of belittling the "Three Vehicles"; but that, since he was talking to an audience already steeped in those teachings, he wished to emphasize that mind-control (Sammāsamādhi) is the highest teaching of all; and that without it all other practices are in vain for those who aim at gaining the mystical intuition which leads to that ineffable experience called Nirvāna.

Buddhists of other sects have often been far less charitable than Huang Po towards those sects with which – usually through ignorance – they have disagreed.. Thus the Pure Land Sect or Amidism is often held up to scorn and labelled "unBuddhist", the "antithesis of Buddhism" and so on. This is partly because many Amidists misunderstand the teaching of their own sect, but what religion or sect would not deserve our scorn if its merits were to be judged by the popular beliefs of the general body of its followers? In fact, as I have stated in the commentary to the text, Amidism in its pure form is excellent Buddhism, for Amida Buddha symbolizes the Dharmakāya (the Buddha in the aspect of oneness with the Absolute), and entrance to the Pure Land symbolizes intuitive understanding of our own oneness with realty. Furthermore, Professor Suzuki has somewhere made the point that more Amidists achieve satori (a sudden flash of Enlightenment) than Zen adepts, because their single-minded concentration while reciting the formula "Nāmo Amida Buddha" is an excellent form of mind-control, achievable even by simple people who have no idea of the true significance of "Amida" and "Pure Land".

Another sect which comes in for much obloquy [censure], especially from Western Buddhist writers, is that commonly known in English as Lamaism. To those who suppose that Lamaism has nothing to offer besides concessions to the superstitions of uneducated Tibetans (more than equalled by the ignorant superstitions found in more "advanced countries"), the Oxford Tibetan Series so ably edited by Dr. Evans-Wentz provides unanswerable proof to the contrary. Huang Po's seemingly discourteous references to other sects are justified by the urgency and sincerity of his single-minded desire to emphasize the necessity for mind-control. The discourtesy exhibited by many sectarian writers would seem to have less justification.

The Division into Sermons, Dialogues and Anecdotes

The sermons alone present the doctrine in its entirety; the dialogues and anecdotes, while offering little that is new in the way of subject-matter, greatly amplify our understanding of what has gone before. This division is quite usual with Zen works. Zen Masters hold that an individual's full understanding of Zen is often precipitated by the hearing of a single phrase exactly calculated to destroy his particular demon of ignorance; so they have always favoured the brief paradoxical dialogue as a means of instruction, finding it of great value in giving a sudden jolt to a pupil's mind which may propel him towards or over the brink of Enlightenment.

Many of the dialogues recorded here took place in public assembly. We must not suppose that the erudite and accomplished P'ei Hsiu asked all the questions himself; for some of them indicate a mediocrity of understanding unworthy of that great scholar.

The Author of the Chinese Version

P'ei Hsiu was a scholar-official of great learning, whose calligraphy is still esteemed and even used as a model by students. His enthusiasm for knowledge was immense. It is recorded of him that, in the intervals between his official appointments, he would sometimes shut himself up with his books for more than a year at a time. So great was his devotion to Huang Po that he presented him with his own son as a novice, and it is known that this young man lived to become a Zen Master of standing.

The Translation

The present translation of Part I differs slightly from one I made several years ago, which was published under the title of The Huang Po Doctrine of Universal Mind; while Part II is now published for the first time. Words tacitly implied in the original or added for the sake of good English have not been confined in brackets, so to some extent the translation is interpretive, but the sense is strictly that of the original, unless errors have occurred in my understanding of it. These probable errors, for which I now apologize, are due to the extreme terseness of the Chinese text and to the multiplicity of meanings attached to certain Chinese characters. Thus "hsin" may mean "Mind" or "mind" or "thought", of which the last is, according to Huang Po, a major obstacle in the way of our understanding the first. Similarly, "fa" (dharma) may mean the Doctrine, a single aspect of the Doctrine, a principle, a law, method, idea, thing, or entity of any sort whatever. Moreover, the text is highly colloquial in places and, here and there, employs a sort of T'ang Dynasty slang, the meaning of which has to be guessed from the context. When I have referred obscure passages to Chinese scholars, I have been given such a wide variety of different explanations that I have not known which to choose. In spite of all this, I believe that my rendering is on the whole faithful and that, at least, I have nowhere departed from the spirit of the teaching. The division into numbered paragraphs is my own.

I am indebted to Mr. Ting Fu Pao's Chinese Buddhist Dictionary, to the Dictionary of Buddhist Terms compiled by Soothill and Hodous, to several Chinese monks and laymen, and most of all to my wife who helped greatly in the preparation of the typescript. It is a Chinese custom to offer the merit accruing from the publication of a Buddhist work to somebody else, and this I gladly offer to my wife, Meifang. I fear, however, that Huang Po would have laughed in my face and perhaps delivered one of his famous blows if I had spoken to him of "gaining merit" in this way!

JOHN BLOFELD (CHU CH'AN)

The Bamboo Studio, Bangkok

October, 7357.