SelfDefinition.Org

Psychiatry, the Uncertain Science

by Richard Lemon

Saturday Evening Post August 10th, 1968

Part 4 of 4

This apparently simple procedure is thoroughly grounded in psychiatric theory, and Dr. Levy was influenced in setting it up by the teachings of many different doctors, among them Dr. Stuart Asch and Dr. Edward Joseph of the New York Psychoanalytic Institute. "These two men taught me that psychotherapy is not an intellectual exercise but a question of getting people to express feelings, often at the most basic level," Dr. Levy says. "And some of my ideas came from Ralph Kaufman, director of psychiatry at Mt. Sinai. I was with him one morning when he passed the room of a man who was suffering from severe ulcerative colitis. The man was depressed, and he saw only a lousy life ahead. He wasn't eating at all. Kaufman walked in with a cigar in his mouth and said, 'Hey, if you don't eat you're going to die.' He began to eat.

"We have found that you can get just about anybody in the state of Maine to come to this place. Within two weeks of the time we started, we were snowed. We often had to say, 'Go home and get sicker, we can't treat you now.' What we've been able to establish here is a system of priorities. At Kings County Hospital, in New York City, the time from reporting through waiting list and treatment was two and a half years. We have no waiting list.

"Yesterday we got a forty-eight-year-old woman in the emergency ward at the hospital. The cops had found her with her head in the oven. She was hysterical when they brought her here, and now they've given her tranquillisers and put her in a security room. She has a logical discouragement. Number one, she has cancer. She started radium and cobalt treatment a while ago.

"They thought they had it stopped, and then she got a return of the symptoms. Number two, her husband walked out three weeks ago without warning. She hasn't heard from him since. Three, her children are grown, and they don't get along well. They hate each other's guts, to put it bluntly. She herself has been an alcoholic, and she talks about one of the sons with hatred. I hope to get her home in two days."

Occasional programs like Portland's notwithstanding, one of psychiatry's greatest failures is its poor overall record in handling psychiatric emergencies. One death in 100 in this country is listed as suicide, but the official figures are probably much too low because of the pressures to list death as accidental in all doubtful cases. One authority says that there are probably 50,000 to 60,000 suicides a year, which would mean a death rate higher than that from auto accidents (many of which probably conceal a suicide); another study has concluded that there are about 250,000 suicide attempts in this country every year.

Yet neither doctors nor psychiatrists are adequately trained to handle these cases. Non-psychiatric interns are often assigned to the emergency wards in hospitals, and their qualifications for assessing mental disturbance are slim. One study of a New York hospital's emergency ward showed that only 144 out of 3,268 patients were referred by the admitting doctor to the psychiatric resident on duty. When 84 patients who had not been referred were studied later, 52 were found to have obvious psychiatric troubles, and 18 more showed probable psychiatric symptoms. A recent A.P.A. study concluded that psychiatrists themselves were no better qualified by training and temperament to deal with emergencies than many other professionals, and could probably learn a good deal from psychiatric nurses and experienced policemen.

Emergency facilities are also in short supply. More than half the country's general hospitals are prevented by their charters from accepting mental patients who come their way; if a man has slashed his wrists, he will simply be patched up and sent home, without psychiatric evaluation. If a patient is physically healthy but clearly disturbed, the only facility in many places is jail.

Psychiatry's record with many chronic illnesses is no better. There are an estimated four and a half million emotionally disturbed children in the country, about one percent of whom have an opportunity to get treatment. (Treatment can easily cost $10,000 a year, and there are only some 1,500 child psychiatrists.) There are about 5.5 million mentally retarded Americans, of whom only 180,000 are in institutions. It is estimated that at least 25 out of every 30 retarded people could, with proper training, lead almost independent lives, but there are not enough psychiatric workers. The National Council on Alcoholism estimates that there are six million U.S. alcoholics, but there is no consensus on the proper psychiatric approach to alcoholism (many psychiatrists recommend Alcoholics Anonymous), and alcoholics and psychiatrists have little mutual attraction.

"They've had very little success in the psychiatric division with people we've sent there,." says Lester Bellwood, an ordained minister who heads Fort Logan's alcoholism division. "One group of patients feels, 'We may be nuts, but at least we're not drunk.' Another says, 'We may be drunk, but at least we're not nuts.'" Psychiatry has done even less work with criminals, yet when 608 convicts at Sing Sing were examined, 60 percent were found to be feeble minded, mentally ill, or psychopathic.

Recently there have been a few promising attempts to find specific approaches. A hospital in Cooperstown, N.Y., has developed a computerised typewriter which has greatly improved schizophrenic children. In a quiet, pleasant voice, it gives the child a word to type. If he punches the wrong key, nothing happens. If he punches the right one, the letter is printed. The machine thus removes pressure on the child by making mistakes impossible.

Two doctors at the Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia have reported success with alcoholics by allowing the patient to drink, inviting him to talk about his life, then filming the discussion. Later the sober patient and the psychiatrist look at and discuss the film, and the sessions are said to make the patient aware of self-deluding aspects of his behaviour. LSD has also been used with some striking effects in treating alcoholics. The dose is large, the aim being to achieve a profound experience which, by temporarily changing habitual ways of responding reveals their inappropriateness and encourages relearning.

Psychiatry is even working with some criminals who are not legally "insane."

The staff of the Kansas State Reception and Diagnostic Centre examine each convicted criminal to determine how much security is required and what treatment will probably be most effective. Of the first group of criminals examined, 423 were sent to the state penitentiary; 480 were sent to an industrial reformatory with detailed recommendations for treatment; 34 went to a state hospital for mentally ill convicts; and 15 were sent to a state hospital outside the prison system.

The proliferation of experimental treatments of all kinds makes psychiatry an energetic profession, but so far it has had almost no success converting its energy into a scientific body of information. As a result, psychiatrists are now in the unique position of helping the mentally ill in many ways and disagreeing among themselves about all of them. But Dr. Paul Wilson is conducting a four-year National. Institute of Mental Health program that may be the first step in bringing order out of this confusion.

A computerized national clearing house for mental health information has been set up. There is a coordinating index to facilitate cross-checking of similar experiments, and there may possibly be patient data, so that if a man from New York has an emergency in California, a doctor there can get precise information about him. So far, some 90,000 technical and scientific documents have been programmed into the computer.

"National registration of patients is probably necessary for good research, although there will have to be very stringent safeguards," Dr. Wilson says." "We hope that accumulating a large body of information about a large number of patients will increase agreement among psychiatrists. Technically this hasn't been possible until recently. Now it's possible for many doctors to be exposed to the same patients and get the same sensory perceptions.

"Whether it's possible to get rid of the political things underneath the disagreements – that's something else."

Almost in unison the psychiatrists came to their feet across the crowded ballroom. It was the banquet of the annual convention of the American Psychiatric Association; the day had been filled with debates about "Unravelling the Phobic Defence," "Socrates and Psychotherapy," and "Information Exchange Modelled in the Time Domain," and now Guy Lombardo, who always plays at the banquet, was inaugurating the dancing with King of the Road. From the four corners of the room they came, sweeping onto the dance floor; in a moment the floor was jammed with bouncing psychiatrists - past presidents of the A.P.A., analysts from Massachusetts and Texas, family therapists from Oregon and Illinois, millieu therapists from Florida, all fox-trotting and smiling together. Every once in a while a head would go bobbing by – Dr. Whosis, originator of the multilinear discombobulation theory, or Dr. Whatis, head of the great Centerville Clinic – and then quickly disappear again into the happy throng.

The Guy Lombardo rite takes place at every annual banquet, and it is probably the only time when a large group of psychiatrists can be seen in one place, smiling. For reasons best left to psychiatrists to figure out, Guy Lombardo is just their cup of tea, and the banquet itself is the one light spot in five days of intense cerebration. The next morning they will return to "Transvestites' Women" and "The Clinical Approach to the Problem of Nothingness" and "Attitudes to Body Products." They will listen to papers and appraisals of papers. At panel sessions they will stand up and say, "I will try not to make a speech but to ask a question," and then make a speech, and they will accuse each other of trying to demonstrate masculinity. But for these few banquet hours, once a year, the psychiatrists of America seem as naturally congenial as a group of hat manufacturers.

It may be difficult for other doctors to comprehend, but there are signs that, in all essential matters, psychiatrists thrive on disagreement.

Every spring the A.P.A. holds a five-day convention which produces some 260 papers, 260 critical analyses of the paper, 25 evening panel discussions, about 50 closed-circuit TV programs, and no firm conclusions.

The performance is reminiscent of a classic experiment in which the Western Electric Co. set out to determine the proper level of lighting for maximum efficiency in a plant. The company put in brighter lights, and efficiency promptly improved. It tried still-brighter lights, and efficiency improved again. Then it put in dimmer lights, and efficiency improved some more. Finally it had an electrician simply take bulbs out and put them back in again, and efficiency still improved.

The inescapable conclusion was that the workers did better when the company made them feel important, no matter how it gave them the feeling. If each bulb had been put in by a different man, and if each man had been a psychiatrist, and if all the psychiatrists had then got together to present their findings, the result would have been an approximation of an A.P.A. convention today.

"Not all of this information is intended to add to our knowledge," Dr. Paul Wilson says. "There's also the publish-or-perish problem. As a result, if a psychiatrist wants to know something today, he's faced with wading through an increasing amount of information he doesn't want to know."

Despite the burgeoning of experiments, there have been few attempts to measure the success of psychiatric treatments, and most of them have been discouraging.

In 1959 Dr. Hans J. Eysenck tabulated 19 reports, covering 7,000 cases between 1927 and 1951, and found an overall rate of cure or improvement of only 64 percent. Comparing that to a spontaneous recovery rate of 66 percent, he concluded that "recovery rates with psychotherapy are little if any better than what could be anticipated from spontaneous and perhaps inherent recovery mechanisms."

No one has yet proposed waiting-line therapy, but about as many people get well while waiting to get into a mental hospital as are cured by being admitted and treated. During World War II, 153 "incurable" patients fled a French psychiatric hospital that was in the line of advance of the Germans. After the war a special investigating commission found that 57 percent of them had re-established themselves in communities, apparently recovered.

There have also been few attempts to find out what characteristics, if any, successful psychiatrists have in common, but several such studies have been striking. In 1954 Dr. John Whitehorn and Barbara Betz studied the doctors of 48 schizophrenic patients who had had a 75 percent improvement rate, and the doctors of another 52 patients who had had only a 27 percent improvement rate. They found that the successful psychiatrists had expressed their personal attitudes quite readily, and had set limits on the amount of obnoxious behaviour they would tolerate. The less successful psychiatrists had been passive or had pointed out patients' mistakes in a detached, instructional way. The successful doctors scored best on aptitude tests for lawyers and worst on mathematics tests, while the less successful ones scored exactly the opposite. The authors concluded that flexible, positive psychiatrists were most successful with schizophrenic patients.

These studies however, exist in a scientific limbo, neither accepted nor rebutted by the profession at large. Only one out of five U.S. psychiatrists does any formal research (as opposed to experimental treatment), and he spends only an average of two hours a week at it. Of the four billion dollars spent every year on mental illness only five percent is spent on research.

"It's frightening how few studies have been done on what works and what doesn't," Dr. Wilson says. "Medicine a hundred and fifty years ago was busy with epilepsy, pleurisy, pneumonia and dropsy, which are only descriptions of symptoms. Psychiatry is still at this level. In medicine you can read one good textbook and be ahead of the wisest man of fifty years ago, but each psychiatrist has to start at zero and work his way up. This mental-health clearing house program is to enable each generation of psychiatrists to start at least half a step ahead of the previous one."

Psychiatry's lack of either a body of knowledge or a consistent theoretical framework has also given it a language some psychiatrists consider confusing and only pseudoscientific. Schizophrenia is often defined as characterized by disordered thinking, withdrawal from reality, delusions, inappropriate emotional responses and disturbed conduct, but, Dr. Wilson says "A person in San Francisco who says 'schizophrenia' means something very different from what somebody in New York means." Similarly all mental disorders are basically divided between the neuroses, which entail little loss of contact with reality and the psychoses, which result in severely abnormal thinking or action, but there is no agreement about whether the difference is one of degree or of kind.

Dr. Karl Menninger's impatient, midwestern voice has repeatedly been raised against the pretentious, meaningless jargon and name-calling which has so long pervaded psychiatry, and which, he believes, tends to discourage relatives, doctors, and the patient himself.

"What a doctor says about a patient may determine his fate," Dr. Menninger has said. "I've seen patients ruined for life by a few words the doctor said. Words are that important. At least three presidents of the A.P.A. have publicly deplored the use of 'neurosis' and 'psychosis' as misleading. 'Neurotic' means he's not as sensible as I am, and 'psychotic' means he's even worse than my brother-in-law."

"The thing that's encouraging to me is that this problem is more apparent than real." Dr. Wilson says. "Dr. Bernard Glueck of the Institute of Living says that if you ask doctors the same questions about the same patients, they'll check the same answers. But if you ask, 'What's he got?' you'll get fifty different answers." Working on this principle, the Institute now uses a computer form for all its nursing notes. The nurse records observations of the patient in 17 areas, in each of which she is offered up to 34 simple descriptive phrases (Appearance: "fussy, fastidious,", "dramatic, theatrical," etc.), with space for additional written comments. The report is then transcribed onto an IBM card and printed in narrative form. The nurses say that they can now tell the doctors things they knew but never had time to write out.

Despite all their internal disagreements, however, psychiatrists tend to be clannish, because it is not easy for psychiatrists to enjoy themselves in the world at large. Many laymen assume that they have a kind of X-ray vision which enables them to read people's minds, and the psychiatrist is frequently regarded with vaguely suspicious awe.

"When I first practiced in Los Angeles," says Dr. Greenson, "I went to Twentieth Century Fox to have lunch with a good friend of mine, Peter Lorre, whom I had known from Vienna. Wallace Beery was with us. Wallace Beery looked at me and then looked away and ate and ate and ate, and finally he said, 'Doc, what am I thinking?'

"Today, some people still think of you that way. It's a tremendous advantage at poker. They attribute to me all sorts of magical powers. They think, 'Oh, he can't be bluffing – he knows what I've got.'"

At the same time, psychiatrists today also suffer from those whom Dr, Greenson calls "the psychiatry worshippers." "It's a new religion to some" he says. "It's a curious way of shirking your responsibilities, as though explaining something excuses it." Dr, Lawrence Kubie once went fishing on a remote island in Canada to get away from it all, and his Indian guide asked his business. Dr Kubie said he was a psychiatrist and asked whether the man knew what that was "Oh yes," the guide said, I consulted one in Toronto last week," The next day the guide's brother asked to go along with Dr, Kubie because he had a few problems he wanted to talk over.

I think that's why we're very clannish as a group, because we're more comfortable with each other," says Mrs. Morton Golden, whose husband is a psychoanalyst in Brooklyn Heights. "My husband and I do maintain a few old friendships outside psychiatry, but on the whole, no. If we go to a party, and we're the only analytical people there we spend the whole evening answering questions."

"All you have to do is go to a dinner party and sit beside somebody who's in analysis and you never heard so many bad dreams," Dr. Robert Campbell says. "Nowadays at dinner parties I'm a proctologist, because nobody will talk about their hemorrhoids."

Nonetheless, psychiatrists have brought some of their problems on themselves. Psychoanalysts have a reputation for being incredibly self-absorbed (Dr. Greenson has written that a surprising number of analysts suffer from stage fright, and may be most comfortable in a chair behind their couch), and many psychiatrists concede that the profession attracts a number of people who are anxious about their own emotional problems.

Psychiatrists often seem to encourage the very myths that they deplore.

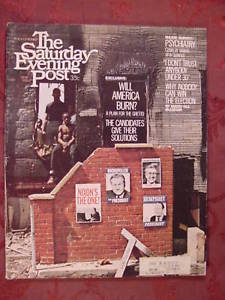

During the last presidential campaign, Fact magazine wrote every member of the A.P.A., asking for an assessment of Senator Barry Goldwater. The A.P.A. denounced the questionnaire, but 1,846 members, or 11 percent, answered it, diagnosing the senator as everything from "paranoid schizophrenic" to "warped." Goldwater was assessed as harbouring a subconscious hatred of his Jewish father; as, having "a mysterious air about him," which might show emotional disorder; as apparently hating and fearing his wife; and as possibly haying had a rigid toilet-training period. A great number of the respondents were listed only as "Name Withheld,." and although the A.P.A. and the A.M.A. accused Fact of yellow journalism, the A.P.A. said little about the charge that 11 percent of its members had practiced yellow psychiatry. Goldwater sued the magazine and won, [1] and most psychiatrists would like to forget the whole episode.

[1. DJT receives such "analysis" and should do the same.]

This segregation of most psychiatrists from most of society is extreme and, to community psychiatrists, alarming. There are 22,680 psychiatrists practicing in the U.S. today. More than half of them work in the 15 largest cities; more than half work or live in the states of California, Massachusetts, Illinois, Pennsylvania and New York, which alone has 21 percent. Psychiatrists tend to vacation during the same month (August), and in the same places (Truro, Massachusetts, Fire Island, N.Y., Rockport, Maine, and Woodstock, Vermont.) Two thirds of U.S, psychiatrists have some private practice, and private psychiatrists report that their typical patient has a college degree. They prefer females, age 20 to 40, and people who are intelligent, attractive, youthful and verbal. (One study of treatment given to poor city dwellers showed that patient and doctor tended to reject each other, and few patients stayed in treatment long.) To insure their patients' privacy, most psychiatrists work alone, without even the company of a nurse.

"What I disliked most about doing only private practice was the loneliness," says Fort Logan's Dr. Kraft. "You see very little of your colleagues. You have little chance to share your experiences. I was in an office with five psychiatrists and it was almost eerie. You'd see their cars when you came in the morning, and again when you went home at night, but you never saw each other "

But despite the community psychiatry movement, there are few inducements to bring psychiatrists into broader work, The typical hospital salary for a psychiatrist is $18,000 a year. (Private psychiatrists get $30 to $40 all hour, or about $40,000 a year.) Psychiatrists speak of the "deadening effect" of working with large numbers of patients, and many of those who do work in hospitals seek a stimulating balance front private practice on the side.

The length of psychiatric training is also an isolating factor. The average U.S. psychiatrist is 46 years old and has been in practice only a dozen years. To become a member of the A.P.A. a psychiatrist must complete eight years of postgraduate training. Yet, like all medical students, future psychiatrists take some 500 hours of anatomy, and only 20 to 180 hours of pathology and psychiatry.

Many psychiatrists of all schools believe that this training must somehow be streamlined if the profession is ever to meet the demands made on it. Dr. Kubic has proposed training lay analysts whose patients would be required to receive periodic examinations by a doctor, and Dr. Greenson has predicted that "we will get to the point where if you want to be an analyst, you won't have to be a doctor." Dr. Rocco Motto, head of the Reiss-Davis children's clinic in Los Angeles. has said, "I don't know the answer, but I don't think it's necessary for a man who will treat children to be trained as an adult psychiatrist first." The George Peabody College for Teachers in Nashville, Tennessee., has found that teachers with one year of special training, working under a psychiatrist's supervision, can deal effectively with emotionally disturbed children. Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, Maryland, is training housewives to become therapists.

The average U.S. psychiatrist works a 44-hour week, plus five hours of unpaid lecturing and counselling, and the work is more straining than is generally recognized. Doctors stand high on the list of suicide-prone professions, and psychiatrists are the most suicide-prone of all doctors. A British psychiatrist has observed that "The explanation may lie in, the choosing of the specialty rather than in meeting its demands, for some who take up psychiatry do so for morbid reasons." But Dr. Walter Freeman has blamed the high suicide rate on "the prevalent notion that only by undergoing a personal psychoanalysis can a physician become a real success in the field of psychiatry," and he suggests that "thorough insight into one's own personality cannot be endured by all who would essay it."

Certainly confidence is recognized as a major contributor to all human effectiveness, and the confidence of psychiatrists is subject to heavy strains. In one startling survey 70 percent of the psychiatrists queried believed their treatment method to be the best – but only 25 percent were fully satisfied with the particular theory on which the treatment was based.

Furthermore, mental illness can be contagious, and the psychiatrist is especially vulnerable. Mrs Pullen, of Idaho's State Hospital North, has a favourite story about a girl patient who one day put her blouse on backward. "Why did you do it up in the back?" Mrs. Pullen asked. "Because," the girl said. "that's where the buttons are." Much of a psychiatrist's time is spent trying to see the buttons from the patient's point of view.

The most cruel challenge of all to a pyschiatrist's confidence is the human mind itself, which sometimes seems deliberately constructed to confound all rules. The Boston State Hospital is conducting a promising experiment in which observers live for a month with 16 families, half of' which have been diagnosed as schizophrenic, and half of which appear normal. The observer spends two and a half hours a day tape-recording information about the family's life, and everything the subjects say is taken down, with their permission, by bugs in each room. So far the study has confirmed earlier findings that schizophrenic families tend toward confused ways of communicating and toward "masking" – doing something not for the apparent reason but for a hidden purpose. But every time the project director has thought he found some new trait in the schizophrenic families, it has cropped up in a "normal" family too.

The psychiatrist, in fact, starts out with only a loose idea of what mental illness is. Freud called the ability to work and love the best indicators of health, and wrote that "as soon as a person begins to question the meaning of life, he is sick."

Many psychiatrists say that a person becomes ill when his unconscious processes dominate his conscious ones, or when the past dominates the present, and the capacity for enjoyment is often cited as an indicator of health. In one unscientific but suggestive study, 14 senior members of the Menninger Foundation wrote descriptions of 80 people whom they considered mentally healthy, and five common denominators emerged. The people judged healthy had a wide variety of sources of gratification, they were flexible under stress, they recognized and accepted their limitations and assets, they treated others as individuals, and they were productive and active.

Similarly, psychiatrists can identify but not explain some factors that affect health. Nationality is one of them. Alcoholism is twice as common among the Irish as among other national groups. Jews are above average in drug addiction and neurosis, and nobody has any real idea why. Heredity is a factor. The rate of schizophrenia among the children of schizophrenics is 16 times the rate for the general population, and children of schizophrenics tend to develop it even when separated from their parents at birth. Once again, no one knows why. There is no evidence that the rate of mental illness is any higher than in the past, but the times are a factor in the form illness takes.

Today there is less bizarre behaviour and paranoia, but more young people have behavioural disorders, and there is more depression in middle and old age.

Generalized stresses also affect mental illness. The Los Angeles County General Hospital gets 10,000 psychiatric admissions a year, almost all on an emergency basis. "A lot of these people have been mentally ill for years, and then some external event stirs them up," says Dr. John Ray, assistant director in the department of psychiatry "The thing that really brought them out in force was the assassination of President Kennedy."

Loneliness and solitude are also generally mentally destructive; the mind may need sensation the way the body needs food. In sensory-deprivation tests volunteers wearing thick suits, helmets and gloves are suspended in air or water in a lightless, soundless room. They can't see, hear, feel, or smell, and under these non-conditions most people experience hallucinations in a few hours. "Much of the trouble on earth is caused by people," Dr. Braceland has said, "but much of the trouble in space will come from not having them."

Confidence and belief are the most dramatic factors that affect mental health. A test question that follows an impossible question will not be answered as well as if it follows an easy one. Patients psychologically resistant to medicine do not get as much benefit from it as those with a positive attitude toward it. A number of people die every year after taking plainly non-lethal doses of poison, a number are cured by placebos with no medical value, and there are reports of addiction to just about everything, including bicarbonate of soda. Belief can even determine what one sees. In one remarkable study, subjects were fitted with eyeglasses which turned everything upside down. After a few days the world began to turn right side up again for these people, and eventually everything looked normal. Then the glasses were taken off, and everything went upside down again. A second period of adjustment was needed before the world came right side up again.

Confronted by the machinations of this awesome instrument, the human mind, psychiatry today reveals a curiously split personality: It is working to break down the old barriers between illness and health, and between the patient and the community, yet many of its practitioners remain firmly segregated from society.

The great question about psychiatry today is whether it will continue to grope its way out of isolation and toward a new role in society. Most psychiatrists seem to think it will, and, in the only real show of unity the profession has ever mustered, they have begun to establish community psychiatry as a bold, new tradition.

On the other hand, as Dr. Charles Meredith, chief of the Colorado State Hospital in Pueblo, has said, "If it's traditional, then we usually begin to question it."

[ end ]