SelfDefinition.Org

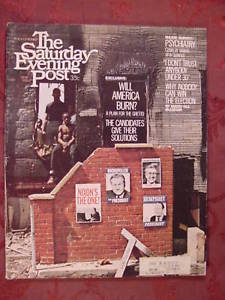

Psychiatry, the Uncertain Science

by Richard Lemon

Saturday Evening Post August 10th, 1968

Part 2 of 4

Few doctors have had any training in psychiatry, and many are sceptical about its effectiveness.

"You have to treat doctors as gingerly as you treat a patient," says Mrs. Morton Golden, who administers her psychiatrist husband's seminar series for doctors in Brooklyn Heights, N.Y. "The young doctors are too busy getting going to come to us, and it also seems to take about twenty years for the doctor to realize that there are patients he's not having success dealing with. When you first approach a general practitioner, you're dealing with a layman."

Community psychiatry has even had its frustrations with psychiatrists. In a study of psychiatric agencies several years ago, Dr. John Curning and Dr. Claire Rudolph found that the agencies with the best-trained workers concentrated almost completely on mildly disturbed patients, and saw only a small percentage of severely disturbed people. Similarly, the agencies with the least-trained workers treated the most people and most of the severely disturbed. There are fewer members of the A.P.A. working in public hospitals today than there were when the organization had only 4,000 members.

"At least half psychiatry's energy today is going to people for whom treatment is essentially palliative," says San Mateo's Dr. Joseph Downing.

"This means people who probably wouldn't be much different if they weren't treated at all. One of our big problems is the dog-in-the-manger attitude of most professionals, that even though they're overworked and can't do a job, nobody else can do it because they're not professionals."

Finally, of course, many of the places where the most ill are treated are unsuited to community psychiatry, which was a major reason for the creation of the community mental-health centre concept in the first place.

The average U.S. mental hospital has 1,440 beds, compared to the non-psychiatric hospital average of 139. Some 452,000 Americans are being treated in 284 state and County mental hospitals, most of which are at least 45 years old; about 40 percent of these patients have been hospitalised for more than 10 years, and almost 30 percent of them are over 65 years old. The country's 259 private mental hospitals have 80,000 patients and five times as many staff members per patient as the public hospitals, and the average stay in them is two months. Many of these private hospitals, like Menninger's, in Topeka, Kansas, and the Institute of Living, in Hartford, Connecticut, have supplied the profession's leaders, but many of the more conservative, less community-oriented voices in the profession also come from such hospitals. Today, still, there are 13 states with no private mental hospitals at all.

The most community-oriented of all hospitals are probably the 1,005 general hospitals that have psychiatric units. General hospitals today actually treat more mental patients than do the state and county hospitals, and more of them have applied to become community mental-health centres than any other class of hospital. Nonetheless, even the general hospitals are a long way from the minimum standards laid down by the National Institute of Mental Health. Only a third of them have any social workers (the average mental-health centre has seven), and only a third offer any form of part-time hospitalisation.

One vivid example of how far psychiatry has come in recent years, and of how far it still has to go, is an old, remote, unglamorous hospital in Orofino, Idaho, which serves the entire northern half of the state.

In the summer of' 1939 a young premed student from California went up to Orofino's State Hospital North to work as an attendant. "It was a dumping ground," he recalled recently. "The big therapy was to push big blocks with carpeting on them, back and forth, to polish the floor. The place was staffed by bughousers – a floating population, like circus roustabouts – who worked in mental institutions. You've read the horrors about patients getting beaten up? – Well, the simple fact was, it worked. The other patients complain that they can't sleep because some guy is yelling, so you went in and beat him up for five minutes. You got a dry towel, never a wet one, and knotted it and beat him. If anybody came along later, there were no marks – maybe a skin rash, nothing else. There was one male nurse who was a sadist. He went in and beat up a patient badly with a towel. I went in and complained to the doctor. I remember he was sitting in the dark, listening to Jack Benny. Nothing ever happened."

Ten years later, after a series of newspaper exposes about State Hospital North, the legislature appropriated money for two new buildings, but by 1956 conditions had still not improved much. That year, a psychiatrist named Dr. Myrick W. Pullen Jr., who was in private practice in Salt Lake City, heard from his father, a doctor in Boise, that State Hospital North was looking for a superintendent, so he went up to take a look.

"The needs just stood out all over," he recalls. "And I knew I could run a place better than that." With no fancier mandate than that, Dr. Pullen became superintendent. "It was fantastic," he says. "The patients were working twelve hours a day, seven days a week. A lot of people were being held here just because they were good workers. People would say, 'You can't let Charlie go home for Christmas. Who'd collect the garbage?' Lock 'em up, keep 'em quiet, and work 'em was the treatment plan, by and large."

Dr. Pullen is a quiet, unprepossessing father of six who favours pale sports jackets and keeps a Methodist hymnal on the upright piano in his parlour. He does not write papers, and he is not known to the leaders of his profession. Nonetheless, thanks to Dr. Pullen, northern Idaho has a very different hospital today. State Hospital North now has 278 patients instead of 435, and 108 of those were admitted before Dr. Pullen arrived. New patients generally get out in a little over a month, and can start trial home visits within two weeks. A family-care program places patients without relatives in a sponsor's home, and discharged patients are provided medicine at cost. Two thirds of the wards are open, and there are two sunny and cheerful self-management wards. There is a well-equipped new laboratory; a room with a see-through mirror and tape recorder, for group therapy; a lively recreational therapy shop.

Two thousand feet up in the mountains, 17 miles from the hospital grounds, patients and staff members are building four A-frame houses as a self-sustaining camp for the hospital's most needy cases, its long-time patients. "We have some of the recreational advantages the rest of the country is crying for, and it would be nice to use them," says Bernard Sargent, the young public health specialist who supervised the camp's founding. "If we can give these chronic patients a group identity, and set up a retreat that is realistic, not escapist, we may help some of them."

State Hospital North is still not a model hospital. Orofino is set dramatically alongside the Clearwater River at the bottom of a deep, narrow, inaccessible valley, and it is hard to get psychiatrists and doctors to work there. Dr. and Mrs. Pullen have had two weeks vacation in 10 years, and Dr. Pullen uses his spare time travelling to professional meetings, to keep informed. "Many patients who come here could be treated in their communities," Mrs. Pullen says, "but there are no facilities.

State Hospital North also carries the burden of its past. The old men's ward has a large sitting area furnished with a semicircle of chairs. Every day, 43 old men in overalls sit there, crying, muttering, gesturing to themselves, sucking toothless gums, and their meaningless jabber creates a susurrating noise like the fluttering of hundreds of moths. Some are incontinent, but they are always cleaned up right away. One old man sings over and over again, "I'm gonna quit, I'm gonna quit, I'm gonna quit."

"These are a lot easier to take care of than most patients," says the old men's nurse, a short, energetic woman. "They're not nearly so demanding. They're all capable of feeding themselves. I like these little old men – there's something about them. This little guy is paretic. He's had syphilis of the central nervous system. He thinks he's God's gift to women. He has a girlfriend – he sits out with her and holds hands. This little guy who's singing, every once in a while I go tell him to be quiet or he'll wake the baby. I got a bunch of characters in here. It's more fun than a barrel of monkeys."

Speaking of a patient in the old women's ward across the hall, Mrs, Pullen says, "I sat, down next to Pearl the other day and said, 'Pearl, how long have you been here?' and she said, 'Thirty-four years.'"

Psychiatry has dramatically improved the way it treats its patients, in the years since Pearl went in, but Pearl is still there. Such patients are no longer considered hopeless, but their hope now lies not in humane treatment but in intensive therapy. The hard problem still facing the profession is this problem of therapy: what specifically to do to help the mentally ill shake off their invisible chains and thus, as Freud put it, return them to the common unhappiness.

Of all the choices presented to psychiatrists in treating the mentally ill, one of the most basic is whether to deal with the patient individually or as a social being, in his surroundings – roughly, a choice between the classic medical approach and what is called the "problem of living" model. With its move out of isolation, psychiatry has also moved away from the medical model toward the social one.

One of the ripe paradoxes of this paradoxical profession is that, in the teeth of this shift, psychiatry's most important single treatment is still psychoanalysis, which is medically oriented, resolutely individual, and has changed hardly at all for 50 years.

Psychoanalysis is by all odds the most complex, cumbersome, limited and time-consuming psychiatric treatment ever devised. Psychoanalytic treatment takes three or four years to complete, the patient must visit his analyst three to five times every week, and full treatment may cost as much as $30,000. But analysis has had little success with the severely disturbed, and many analysts use it on only a few of their patients.

The few studies that have been made indicate that analysis, even with its selected clientele, succeeds only two thirds of the time, a rate not distinguishable from spontaneous recovery rates after no treatment at all. Analysis has therefore come under heavy attack from those who want to treat mental illness on a large scale or within a brief amount of time.

Freud is the only practitioner in the history of medicine, Dr. Garfield Tourney has written, to introduce a treatment which has "proved to be lengthier and lengthier, more expensive and applicable to fewer patients, with dubious results."

"Analytical training slowed me down for five years," Dr. David Vail, chief of Minnesota's mental-health program says. "It's not only of little use in the world of everyday reality – it can actually cripple a psychiatrist's ability to deal with everyday reality. It's like trying to survey ground for a highway by using a microscope."

Yet for all its limitations, analysis is still a powerful force in psychiatry. Half the heads of psychiatric divisions of medical schools are analytically trained. They tend to be the intellectuals of the profession and, often, the leaders of its organizations. Leading analysts in New York are finding themselves with unfilled appointment periods, but its general popularity with patients is still high. (One 10-block section of Manhattan is so crowded with analysts that it is known as "The Mental Block," and its Beverly Hills equivalent is called "Couch Canyon.") Most important, whatever its therapeutic value, it is probably the best technique yet devised for revealing the hidden mind. "Saying that Freud is out," Dr. Kubie says impatiently, "is like saying Newton is out because Einstein came along."

Of all psychiatric procedures, the technique of psychoanalysis is at once the most scientific and the most artistic. Analysis is the only psychiatric therapy with clearly established ground rules, and although there are many dissident schools, the majority of analysts still consider Freud's rules sacrosanct.

At the same time, the application of those rules demands an ability to react spontaneously to the patient's material, much as the creative artist reacts to contact with the variables of life. The analyst must constantly decide whether to speak or keep silent, whether to suggest interpretations to the patient or wait for him to come to his own conclusions, and whether what the patient says is true or evasive, trivial or significant. To do that, the analyst tries to share the patient's feelings, then pull back to examine the feelings objectively in the light of analytic theory, clinical experience and his knowledge of the patient. For his part the patient is asked to alternate between free association and rational discussion, between total subjectivity and objective efforts to understand.

Analysis is thus not a straight-line process, with the patient tossing out whatever comes into his head and the analyst explaining what it means, but a constant shuttling back and forth by both doctor and patient between expression and interpretation. The treatment part of this process is altogether indirect. "I wouldn't even speak of treating a case in psychoanalysis," Dr. Robert Waelder has said. "We study a case in psychoanalysis." Nevertheless, many analysts believe that their most successful colleagues are those with a strong desire to help people, and the cornerstone of analysis is the belief that study and understanding eventually lead to recovery.

Each patient's mind presents a new continent for exploration, but it is a peculiarly tricky continent filled with mirages. The patient, a resident of this continent, is befuddled by these mirages: He puts on a bathing suit to go up a mountain because it appears to him as the ocean; he runs from flower's because they look like snakes; he becomes paralysed looking at an apple tree because it calls to his mind a forbidden grape arbour from his youth. Yet his conscious mind isn't aware of these misconceptions, so he can explain his actions only by saying that he finds mountain air warm or the smell of flowers overpowering or apples fearful. At first the analyst is as lost as the patient, and only through slow and careful tracking down of leads can he come to understand what lies behind the mirages and thus lead the patient to the same knowledge.

It is no use to tell the patient a flower is not dangerous, because the patient already knows that. It is no use to tell him he sees a flower as a snake, because he will not be able to believe it. It is necessary first for the analyst to discover that flowers do appear to part of the patient's mind as snakes, then to find out what there is about flowers that causes them to appear as snakes that made them frightening in the first place and, finally, to lead the patient to the same discoveries.

The ground rules for this difficult exploration were evolved by Freud from his own observations that certain basic formations are common to all men's minds. The part of the brain containing the unconscious instinctive drive Freud called the id. The largely conscious part of the brain Freud called the ego; its function is to mediate between the instinctive drives and the demands of reality. The third major – and largely unconscious – part of the brain Freud called the superego; this he described as a kind of policeman, or conscience, in which "the parental influence is prolonged."

The ego pushes back any drives from the id which reality or the person's superego can not tolerate and this process of repression is what creates neuroses. It was Freud's belief that man is driven primarily by his love, or sexual, instinct and by an aggressive, destructive, death instinct and that all neuroses are created by a clash between the sexual instinct and the ego during childhood. The basis of psychoanalytic treatment is that what has in this way been rendered unconscious must be made conscious again, and when this has happened, the neurosis will disappear

The existence of the unconscious is clearly established. Experiments have shown that if a man spends a few minutes in an unfamiliar room, and then is asked to list as many of the furnishings as he can, he will average 20 to 30 items, but if he is then hypnotized, he will be able to list as many as 200. Most people find this hidden mind fearful and even shameful. Carl Jung spoke of the widespread "panic fear of the discoveries that might be made in the realm of the unconscious," and Freud himself once told Jung that he had made his sexual theories into dogma as a bulwark against a possible "outburst of the black flood of occultism." [1] Even today most laymen are far happier with the idea that there may be a chemical cause for mental illness. "People would prefer a physical diagnosis," says Dr. Robert Buckley of Los Angeles. "Even a brain tumour."

[1. See review, Andrew Blackman, Feb. 2008: "The Undiscovered Self" by Carl Jung, at andrewblackman.net ]

A great limitation of psychoanalysis is that a confrontation with the unconscious mind is not always feasible – or even desirable. The physical symptoms of hysteria are often a last-ditch effort to ward off an unbearable mental showdown, and patients have been cured of hysterical paralysis and committed suicide the night of their recovery.

Freud discovered that if a patient simply let his mind roam and then reported the associations that emerged patterns would be revealed which could be discovered in no other way. Free association is thus a means by which the unconscious speaks – dreams are another – and the patient free associates for most of the analytic hour.

The major tool of the analyst is interpretation of these associations, but even interpretation must await confrontation: The analyst cannot suggest what a fear may mean until the patient has admitted having it. Then, if the interpretation is correct, it will produce fresh material, new recollections and further interpretation.

The barriers put up by the patient's ego to prevent this uncovering are called resistances. A resistance may be conscious or unconscious; in general, it is anything that blocks free association or insight. Resistance is present at every step, and is always the first thing to be analysed, although most analysts let minor resistances go by the board to avoid turning exploration into prosecution.

Resistance is often artful and hard to detect, but it can also betray itself in some familiar ways. A patient who talks at length about trivial things is probably avoiding something, and so is one who talks constantly about either the past or the present. Figures of speech like "honestly" and "really and truly" suggest their opposites, and a patient who talks blandly but squirms and wiggles is probably not telling the whole story. Clenched hands and locked ankles are figurative signs that something is being held back.

Dr. Ralph Greenson tells of one patient, a highly intelligent professor, who always reported his dreams by starting in the middle and jumping around. It turned out that the man also began reading books in the middle, had always done homework from the middle or end, and studied walking or lying down. The professor's father had been a famous teacher and had groomed the son to follow in his steps. The professor had felt great love for his father, mixed with deep hostility and jealousy and a fear of being swallowed up by his dominating parent. His love had been expressed in following the, father's career; the need to rebel had been expressed in his odd ways of going about it.

The most crucial and curious phenomenon of analysis is known as transference. In transference a person in the present – the analyst – is reacted to as though he were a person from the patient's past, usually father, mother, sister or brother. By unconsciously reviving this past figure the patient re-experiences during treatment the significant but repressed events of his past. Transference occurs because an ill person tends to re-experience emotions instead of remembering them, and the psychiatrist encourages the development of a transference so that the patient will be able to look at this mirror version of old relationships.

The subtle and much misunderstood process by which the patient recovers hidden childhood emotions is called reconstruction. "We are misled if we believe that we are, except in rare instances, able to find the 'events' of the afternoon on the staircase when the seduction happened," Dr. Ernst Kris has written. "We are dealing with the whole period in which the seduction played a role." Analysis does not so much attempt to recapture the feelings and reactions of this period as to reconstruct a facsimile of them, but even a taste of old feelings can produce extreme regression: patients may shout, curse and weep, and psychotic reactions sometimes occur.

The last stage of analysis is called "working-through," and it is the slow process of removing resistances which have not been affected by insight. Much of working-through takes place outside the office.

The most subtle aspect of psychoanalysis is probably the relationship between the analyst and the patient. During this delicate relationship, the analyst's notorious couch serves as a specific tool to expedite free association. The act of lying down is infantilising; it makes the patient's thinking looser and more pictorial. (It is hard to give one's mind free rein while staring a doctor in the face, and the sense of isolation on the couch, with the doctor out of sight, creates a strain which brings feelings to the fore.) For his part, the analyst listens to the uncensored flow of thoughts with what is often called "free-floating attention." He uses his own reactions as a major guide, and many psychoanalysts believe that their own unconscious insights are more important to them than their intelligence.

"If things get boring, and I get sleepy," says one New York City analyst, "it's an indication that I have to make an intervention. He's probably muddying the waters to hide something."

At the same time, the analyst absents himself as an individual from the proceedings is much as possible. His blankness lets the unreality of the patient's reactions be demonstrated; if his own personality becomes involved, he injects a complicating element into the transference. "The doctor should be opaque to his patients," Freud wrote, "and, like a mirror, should show them nothing but what is shown to him."

The specifics of successful analytic cases are as varied as individual personalities, but they share a common quality – a painful, seemingly interminable peeling away of emotional coverings.

In New York, a depressed, masochistic mother of two began analysis because of the realization that she seemed to need to make herself feel unhappy and badly used. She had greatly admired her two younger brothers, who she felt were her parents' favourites and who frequently showed off for her intellectually and artistically, and during the first year of analysis she gained psychological insight into her resultant feelings of deprivation. But the insight left her in times of stress, and the analyst felt that her treatment was going around in circles. Then he noticed that, during analysis, the woman went through an odd and unvarying ritual. She would relate a dream or incident, then lapse into a dreamy silence and wait, her head slightly turned and her mouth open, in anticipation of an interpretation. If he gave one, she would say it was marvellous, a brilliant deduction, and comment on her own stupidity. Then she would say she felt depressed. He would interpret her depression, and the routine would begin again.

The analyst decided to concentrate his interpretations not on what she said but on her state and behaviour. For the first time his observations were not met with cheers. The woman complained that he was making her feel uncomfortable, accused him of losing interest in her, and said treatment wasn't getting anywhere, He suggested that she was angry because he had interfered with the dreamy state in which, both in treatment and outside it, she experienced a kind of passive sexual excitement.

The next day the woman reported a nightmare involving a male figure, from her childhood, and the details led the analyst to ask whether she had ever had a childhood experience with an exhibitionist. She suddenly recalled a forgotten incident, which she had been too ashamed to tell anybody about, of mutual fondling with a young man when she was eight. The analyst suggested that her state during this incident was the same dreamy one in which she had admired the exhibitions of her brothers and now of the analyst, and that her subsequent depressions duplicated the shame she had felt after the fondling. The woman thereafter improved considerably, with only occasional spells of depression, and the analyst decided to end treatment.

Three months before the anlysis was to end, the woman had a third child. Her mother came to help her for a month, then left to visit one of the patient's brothers. The woman took up an old habit of compulsive eating, gained a lot of weight, and then went on a crash diet. At that point a snowstorm prevented her from keeping two successive appointments.

When she next came in her appearance was unkempt, she spoke stuporously and moved haltingly and clumsily. She was depressed and full of complaints about household drudgeries. The analyst said she looked less like an overworked housewife than a neglected child, and the woman started to cry. Then she reported a recent dream in which she was locked out of her parents' house. The analyst suggested that she looked and acted the way she must have at 19 months when her mother gave birth to her brother and thus "left" the patient for her brother, as she had left after the recent birth of the patient's third child.

He suggested that the crash diet repeated a childhood hunger strike, and that the snowstorm that kept her from the analyst had made her aware that still another relationship was about to be broken off, and that she would once again be replaced, by another patient. She was re-experiencing the same envious, hurt reaction to being locked out that she had known as a child. The woman became brighter, and confessed that she had recently been preoccupied with thoughts that maybe, when she left, the analyst would treat her brother, who had been considering analysis. The insight was worked through, her depression vanished, and treatment was ended. The essential factor, the analyst concluded, was not the recollection of childhood events but the reconstruction of the childhood emotions.

Analysis is the most difficult of all therapies to evaluate, but many of its current troubles seem due to factors which have nothing to do with the treatment itself. "The three men who have caused the greatest blows to man's esteem are Copernicus, Darwin and Freud," Dr. Greenson has remarked, and analysts from Freud on down have believed, that the field has often been attacked because it probes an area which most people would like left alone. In addition, analysis attempts to reconstruct the personality, which, sounds as alarming to most people as a proposal to redesign the flag, Evangelical patients may also have hurt the profession. "I think analysis has suffered more from its friends than its enemies," Dr. Greenson says, "because many of its so-called friends are insufficiently analysed patients."

The vogue of analysis among creative people, especially actors, has also created a mistaken impression that it is a kind of pacifier for the temperamental. "All artists are disposed toward neurosis, or their creativity is a substitute for neurosis – you see both," Dr. Greenson says. "But actors are, I would say, among the least rewarding of patients. People who get too much acclaim tend to develop narcissism, and there's a premium on being infantile in the movies. It's pretty rough to try to get somebody to have a sense of reality when he's getting a million, a million and a half bucks per picture."

Finally, analysts themselves tend to be quarrelsome and prone to dogmatism, and they often put their worst foot forward. The size of their judgments often seems in inverse proportion to the amount of the evidence. Many analysts, including Freud, have made large judgments about famous people they have not met, and it is not uncommon for analysts to dismiss their critics as emotionally unbalanced. Yet many analysts also like to compile reams of minutiae about their patients, from which they are able to deduce almost nothing. One recent analytical paper was entitled, "The Effect of a Change in the Analyst's Visage Upon Transference," and dealt with the effect on his patients when an analyst came back from vacation sporting a beard. The paper concluded that there wasn't any important effect, although one patient briefly wanted to call the whole thing off.

The most serious charge against analysts – and it has been made by some leaders of the profession – is that they have been unwilling to try to modify a cumbersome procedure. Dr. Leo Rangell, a past president of the American Psychoanalytic Association, has spoken of the "definite and discernible period of decline" of the specialty, and he blames it in part on analysts' haphazard approach to research and their lack of "creative, imaginative, or free thinking." At one convention Dr. Robert Waelder was asked whether analysis could be shortened. "It still takes nine months to have a baby," he answered, and the audience of analysts burst into applause.

"I am amazed at Bob Waelder for hauling out that old chestnut," Dr. Karl Menninger told the audience. "I think it's a ridiculous metaphor. There's a presumptuousness about it that assumes that in some divine way we analysts are presiding over a process as immutable as reproduction." Dr. Menninger got no applause.

While analysts study the mind to produce insight, psychotherapists generally manipulate and direct in order to change behaviour, and individual psychotherapy follows no rigid pattern. Treatment may be given twice a week or twice a month, and it may last anywhere from ten or 15 visits to several years. The patient generally sits facing the therapist, partly because severely ill patients need to maintain relations with another person and couldn't stand the isolation of the couch, and partly because free association is too slow for a limited schedule.

Talk about the past is apt to be discouraged, and the therapist focuses the discussion on the most sensitive areas, interpreting as much as possible. Some drug use is often essential, and advice and counselling are fundamental to treatment. Where the analyst encourages transference, the psychotherapist discourages or manipulates it. Where the analyst is blank, the psychotherapist's opinions and reactions are an open part of treatment. Where the analyst interprets resistances, the psychotherapist evades them, or overcomes them, or strengthens them to keep the patient from slipping into a psychotic state.

There are a number of specific schools with rules of their own. In the Adlerian school, the psychotherapist tries to find out what the patient's "life-style" is and what function his disorder serves. In transactional therapy, the doctor intentionally assumes attitudes or roles toward the patient in order to manipulate, for therapeutic effect, the "transaction" taking place between him and the patient. In nondirective therapy he neither manipulates nor interprets, but offers acceptance and a climate of understanding to liberate the patient's emotions and latent capacities.

The wildest therapy of all is probably that of Dr. James L. McCartney, an A.P.A. member for more than 30 years. Dr. McCartney has written that a female patient needs to work out her libidinal drives if she is to reach maturity, and so he has personally obliged over a hundred female patients with sex play, ranging all the way from lap-sitting to sexual intercourse.

The various forms of individual psychotherapy, taken together, probably form the largest category of treatment today, and even many analysts are using shorter therapies on most of their patients. The patients of one leading New York analyst, on a typical 11-hour day, included a newly remarried woman suffering from guilt about her divorce, an unfaithful wife suffering guilt and anxiety, a college girl, a college boy, a foreign student, an old woman suffering from depression, a homosexual boy with cancer, and a businessman with a tendency toward alcoholism. Only the unfaithful wife and the college girl were receiving formal analysis. The rest were getting counselling or psychotherapy.

A patient's treatment is often limited as much by his own expectations as by the therapist's conviction, and one of the deciding factors may be the patient's attitude toward drugs and self-examination. "In one Bronx clinic, psychiatrists treating poor people find that they want to get a pill from a doctor," Dr. Campbell says. "Here in Greenwich Village we get a lot of hippies and beats, and they know more psychiatric theory than my residents do. They'll take a pill only if the effects are incidental. If it starts making them feel better, they want to stop, because they aren't getting any insight."

In almost every respect, treatment with psychotherapeutic drugs is unlike treatment by either analysis or psychotherapy. Mind drugs work rapidly, sometimes almost instantly. Their effectiveness is clear and measurable, but they give no insight, and there is little knowledge about how they work. Drugs have proved ineffective against hysteria, and they are very rarely given during formal analysis. Nevertheless, 82 percent of this country's psychiatrists say that they use drugs, and the true percentage may actually be even higher since psychiatrists may unconsciously play down their reliance on drugs. (One survey showed that 92 percent of all analysts use drugs at least occasionally when treating schizophrenia.) Pure drug treatment, without accompanying therapy, is relatively rare, but there are few therapies today in which drugs do not play an important part.