SelfDefinition.Org

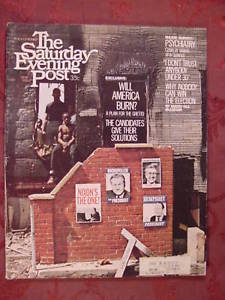

Psychiatry, the Uncertain Science

by Richard Lemon

Saturday Evening Post August 10th, 1968

Part 1 of 4

[Note: This article is included on the website because it was referenced in a lecture by Richard Rose dated Sept. 8, 1974 at the Theosophical Society in Pittsburgh. He quoted statistics that appear on this page in the paragraph noted below.]

Of all man's disorders, the most infuriating to both sufferer and observer are those that seem to have no cause, If the disorder is physical, it has at least a passable respectability. If it is something other than physical, it is irritating, unattractive and, worst, not understandable. Even the most sympathetic people will tend to feel, in some far corner of their hearts, that if the sufferer would just show a little more willpower or self-control, the trouble would go away. The sufferer himself will probably try that. If it doesn't work, he may well take to drink, or pills, or sex, or change jobs. If none of those efforts work he is likely to go to his minister, or his family doctor.

If none of them is able to help, and the disorder is still bad enough, he finally goes to a man known as a psychiatrist. What this man does, and what he is supposed to do, are subjects of great confusion among laymen, ministers, doctors and even psychiatrists themselves, but in broad terms his assignment is clear. He is supposed to ascertain the cause of a disorder that appears to have none, and then somehow get rid of it.

There are many unnecessary causes for the confusion surrounding this peculiar profession, including many laymen's mistrust and fear of psychiatrists, and many psychiatrists' reciprocal mistrust of laymen, but most of the confusion is both justified and appropriate. Psychiatry is a very young and imprecise science, and it has never found a workable definition of itself. On top of that, it has recently been expanding so rapidly that it has burst what were once regarded as its seams.

In the lecture noted at the top of this page, Richard Rose quoted statistics from the following paragraph:

Since World War II [the article is dated 1968] the number of American psychiatrists has quintupled. Since 1955 the number of Americans admitted to mental hospitals has risen four times faster than the population. But today's psychiatrists are experimenting on a scale and with a vigour unmatched in the history of mental treatment, and they have drugs that early psychiatrists only dreamed of. As a result, the average length of stay in mental hospitals has been cut in half, and there are now one fifth as many patients in those hospitals as there were in 1955. And as part and parcel of these developments, the profession of psychiatry itself has been edging out of the unnatural confinement in which it has traditionally been kept and is trying, with uneven success, to join the mainstream of American life.

It is not surprising, then, that the profession's attempts to define itself are today even less satisfactory than they used to be. Psychiatry is usually called "a medical speciality treating disorders of the mind," while psychology is "the study of the mind," and in many ways these definitions are meaningless.

To begin with, psychiatry is not really a "speciality," but a broad field, and it is no more possible to specify what sort of treatment a patient will get from a psychiatrist than it is to say what will happen when he goes to a doctor.

Furthermore, all of psychiatry will not even fit under the heading "medical." Psychiatrists are medically trained, while psychologists aren't, but some psychiatrists do not even define the disorders they treat as illnesses, and much psychiatric treatment is becoming less medically oriented all the time. Finally, some psychiatrists even object to defining the disorders they treat as "disorders of the mind." They say the disorders are emotional, or behavioural – or, as some drug therapists believe, physical.

The most basic characteristic of psychiatry is that, far from being a medical speciality, it is intrinsically uncontainable and spills over into every area of human endeavour, including philosophy, sociology, physics, chemistry, religion, government and art. This untidiness is innate, for the simple reason that all psychiatric theory must start by defining man and his nature, and psychiatry has not one but many definitions of man. Sigmund Freud's is the only doctrine that has any wide acceptance in psychiatry today, but it is also widely challenged and even more widely modified.

The Freudian psychiatrist sees man as having an unconscious, which influences and sometimes dominates his actions, and which contains a number of repressed sexual and aggressive drives. Followers of Alfred Adler see man as dominated by his aggressive instincts, and believe that he can be understood only in terms of the goals he sets himself and his movement toward them. Carl Jung declared that beneath man's individual unconscious there is a racial unconscious, and below that a universal unconscious mystically shared by all men of all time. Existential psychiatrists belittle searches for the causes of disorder, and concentrate on studying the disorder itself.

From these contradictory beginnings, psychiatry has developed a wide variety of equally contradictory ways of treating its patients. People are being treated today with as few as six treatments and for as long as 10 years. Treatment is given by psychiatrists, psychoanalysts, psychologists, social workers, psychiatric nurses, psychiatric technicians, trained housewives, general practitioners, and all combinations thereof. Patients are being treated in remote hospitals, community mental-health centres, hospitals to which they go only by day, hospitals to which they go only by night, in private offices and homes, and they are paying anywhere from nothing to $30,000 a year. They are being treated singly and in groups, as families and in groups of families, and they are being given psychoanalysis, drugs, electric shocks, hypnosis – or simply advice and reassurance.

The variety of psychiatric experience today, therefore, is enormous.

-

At a clinic in Portland, Maine, a girl pays her first visit to a psychiatrist. She is young, pretty, intelligent, has four children, and has recently been deserted by her husband. Now she is depressed, anxious and frightened of herself. "I'm afraid to spank the kids," she says. "I'm afraid that I'll hurt them. They don't seem to please me. I came close to trying suicide, but I realised I'd only be hurting myself." The psychiatrist says he is sure his clinic can help her, gives her two prescriptions, and arranges to have a social agency "homemaker" help her at home. After 40 minutes she is launched on a six-treatment program with limited goals and a very high rate of success. This clinic has treated 500 critically ill people in 14 months, and 493 of them have been able to stay out of a hospital and keep functioning at home.

-

In New York City a 24-year-old man visits a psychoanalyst. He has lost his job. He is emotionally crippled with depression, anxiety, tension, work inhibition, social and sexual inhibitions, facial tics, a peptic ulcer, fear of aeroplane travel, fear of blacking out while driving, fear of horses, fear of losing his temper and killing somebody. For three years he undergoes analysis three or four times a week. He becomes aware of various unconscious parental dominations, and frees himself of them. His ulcer disappears; he gains confidence. For five more years he makes intermittent visits to the analyst about specific problems. After eight years of treatment he speaks with quiet assurance and animation, is happily married, owns and operates a thriving export-import business.

-

In Orofino, Idaho, State Hospital North applies to the National Institute of Mental Health for funds to build a new camp in the mountains as an experiment in rehabilitating chronic patients who have grown dependent on the hospital environment. The camp will be largely self-sufficient, and the patients will be asked to exercise responsibility. If they do well, they will go to a self-management ward in the hospital, then to trial visits outside it. Among the therapeutic instruments the hospital requests are two power saws, three picks, six shovels, four wheelbarrows, six rakes, two brush hooks, a wrecking bar, four axes and two sledgehammers.

-

In Topeka, Kansas, the prestigious and private Menninger Foundation worries that its staff may not be participating enough in the community. It takes a survey and finds that 44 of its doctors are advising some 55 organisations, including the Topeka schools, Leavenworth prison, the Topeka Police Department, the Kansas Council of Churches, the Campfire Girls and the Strategic Air Command.

-

In Pueblo, Colorado, a state-hospital employee unlocks the door to a ward housing the sickest and oldest patients. In a large, bare room, a thin, birdlike old lady, who years ago murdered her husband, sits with her feet twisted awkwardly through the rungs of a chair. "They took out my eyes and gave me new eyes," she announces. "If I hadn't married that Robert, nothing would have happened." A few feet away, a large Negro sits at a table, smiling vaguely. He has one leg and wears four hats, one on top of another. A tall woman walks by. "I used to be very rich, and they tortured me," she says pleasantly. "I was terribly rich. But I'm not on the state. Thirty-five dollars a month I pay here. My daughter has the receipts." Outside, the employee says, "Five years ago those patients would have been sitting in their own vomit. Now those people are bombed. Without their medicine, they'd be taking the paint off the walls. If today's conditions pertained when they were admitted, they'd be out now."

Given the wide range of psychiatry's activities, it is useless to try to find a definition to cover them all. It is more profitable to describe psychiatry generally handles those it treats. When a person with a physical complaint goes to a doctor, he will get one of many available treatments, and the selection is made on medical grounds. The treatment meted out to a psychiatric patient today is usually determined by what's available where he lives, what he can afford, and what kind of psychiatrist or psychiatric facility he chooses. The patients come from all ranks and stations, some have obvious, immediate problems and some don't, some act crazy but many don't, some are functioning successfully in the world and some aren't.

Whatever their troubles, almost all these people come to treatment with the patient's natural expectation that he has something fairly definite wrong which a doctor can fix up, but the characteristic common to the largest number of psychiatric treatments is that they are not specific. Psychiatrists do not locate and remove mental gallstones or even diagnose and cure specific emotional infections. (The only psychiatric treatments that produce definite, predetermined results are drugs and other physical treatments, and there are strong differences about how and when they should be used.) In analysis, sudden insight sometimes brings quick improvement, but that probably takes place in fewer than five percent of analysed patients – a small minority of all psychiatric patients – and it rarely occurs unless the trouble was caused by a specific, buried, traumatic experience. Psychiatric recovery is generally a slow and invisible process.

There are seven principal ways in which psychiatrists help people today:

-

They give, or enable a patient to attain new insight into his mind and emotions.

-

They give guidance, by intervening in the patient's ineffective ways of acting.

-

They foster relearning, or different ways of reacting to stress.

-

They prescribe drugs.

-

They give other physical treatments, primarily electric shock.

-

They offer support and reassurance.

-

They offer and rest and relaxation, usually in a hospital.

In various combinations, these several ingredients constitute the five primary psychiatric treatment in use today:

Psychoanalysis is aimed at enabling the patient to achieve insight into his unconscious mind, and classical analysis strenuously avoids all other methods of psychiatric relief. It is the only major form of therapy which has clearly established ground rules, though in practice the rules have to be played by ear. The patient lies on a couch and reports his feelings through free association, while the psychiatrist relies on interpretation to bring the patient to an awareness of these feelings.

A widow in New York becomes paralysed when a gentleman caller arrives at her door. During, analysis she discovers that the paralysis sprang from feelings of guilt over suppressed sexual desire, and the paralysis disappears. She then rediscovers a buried memory: As a girl, she had been seduced by a cousin, and her aunt and uncle, who had been raising her, called her a streetwalker and threw her out of the house. Her paralysis had symbolically and literally prevented street-walking. Understanding these suppressed feelings, she loses her guilt over them.

Psychotherapy is individual treatment using techniques other than or in addition to those of analysis. Psychotherapists may use drugs; they give less insight, more guidance and support, and always play an active role. The patient usually faces the psychiatrist and treatment takes from six to 15 visits.

A college student in New York has obsessive thoughts about doing away with himself and can't get to college for fear of driving off a bridge on the way. He is a strict Catholic in love for the first time, has considerable buried aggressiveness toward his domineering mother and his church, and feels guilty about sexual desire for his girl friend. Without trying to reshape his underlying psychic structure, the psychiatrist reassures him that his feelings are not unusual, and that there is a great difference between having feelings and acting on them. He tells the boy not to fear his impulses and to express his feelings more. The boy starts expressing himself more in classes and even occasionally yelling back at his mother, and his symptoms go away.

Chemotherapy is treatment by means of drugs. Insight never plays a part; guidance and support play secondary roles. (Some psychiatrists rely primarily on drugs, and psychoanalysis is the only treatment that does not use drugs at all.)

A woman in New York has a recurring, incapacitating depression. She has spent several years in and felt it helped until the depression came back as strong as ever. The psychiatrist gave her an anti-depressant, and her depression disappears. Thereafter she is given the drug whenever she feels a deep depression coming on, and is taken off it over the course of several months. She is able successfully to resume a good job in publishing.

Milieu Therapy helps a patient to recover through manipulation of his environment in a hospital. Insight generally plays a minor role; rest, relaxation, support, relearning and guidance play major roles. Most hospitals, while trying to provide healthy surroundings, do not use milieu therapy in any formal sense.

Group Therapy is a treatment in which the patient is also a therapist to his fellow patients. Under a psychiatrist's unobtrusive supervision, a group of patients discuss their troubles and feelings, and both give and get support, reassurance, relearning and guidance. Group therapy is seldom the sole treatment given, and is most commonly used in hospitals or with outpatients.

It is a startling fact that nobody can say how well any of these treatments work. Evaluation is difficult because there are no cures in the strict sense, while improvement and recovery are matters of subjective judgment. Research comparing treatments has been very skimpy, and psychiatry today has no sizable body of statistical proof to verify the effectiveness of any of its methods.

Furthermore, psychiatrists as individuals are prickly and prone to disagreement. "There's almost nothing I can say that any of my colleagues won't disagree with," Dr. Lawrence Kubie, of Baltimore's Sheppard-Pratt Hospital, said recently, and that statement is one of the few that most of his colleagues could agree with. Psychiatrists today do not even speak a common language; leaders of various schools will refine their lingos to the point where they baffle each other. "I give you the assurance," Dr. Karl Menninger [1]has said, "that I don't understand a good deal of what my colleagues are talking about."

[1. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Karl_Menninger ]

Instead of working to break down these differences, psychiatrists of different persuasions are apt to be segregated from one another. Confidence is recognized as an essential element for therapists as well as patients, and, whether by design or inclination, psychiatrists tend to work and associate with others who share their beliefs so that informational exchanges are erratic. As a result, psychiatry in many ways today is like a large medieval country with a number of isolated fortresses. The inhabitants of one fortress may express admiration for the strength and ability of an opposing army. They may, between battles, meet and talk and even break bread. But to a great extent they are isolated and in a state that either is, or looks an awful lot like, war.

It isn't surprising that a profession in such shape should put off many who have come into contact with it. Some informed people consider it all bunk. Many more consider most of it bunk. (The psychiatrist is sometimes defined as "a Jewish doctor who can't stand the sight of blood." Another underground definition holds that psychiatry is "an unidentified technique applied to unspecified problems with unpredictable results, for which rigorous training is recommended.") But there are three factors which, as Dr. Robert J. Campbell, chief of the community mental health division at St. Vincent's Hospital in New York, has written, argue against "dumping the whole bit on the rubbish heap." One is the fact that psychiatric disagreements sometimes appear more intense than in practice they really are. The second is that all forms of psychiatry probably affect patients, whether for the better or not, and many therapies have demonstrably worked. The third, and most important, is that despite its wrangling and its lack of established methodology, psychiatry in the past decade has more in the treatment of mental illness this decade than during any decade min its history.

In short, psychiatry today is a remarkable profession: wracked by dissension, lacking established rules or practices, unsure of its proper role in society and flourishing anyway.

The profession of psychiatry today is not only radically different from what most people think it is, it is also radically different from what it was a dozen years ago and in another dozen years it will be radically different from what it is today. [article is dated 1968]

At any given time about 600,000 Americans are patients in mental hospitals, about 500,000 are attending outpatient clinics, and almost one million are visiting private psychiatrists. The country's mental hospitals, less than 10 percent of all its hospitals, house half its hospitalised patients. The American Psychiatric Association estimates that these hospitals still have only 57 percent of the number psychiatrists they should have, and 23 percent of the nurses. Two thirds of the patients in state mental hospitals are getting virtually no treatment at all. These patients, however, are mostly leftovers from psychiatry's past, people who got sick too long ago to benefit from recent advances. [2, 3, 4, 5]

[2. After "de-instititiomnalizan" some are now living with caregivers and others are sleepng on cardboard boxes on the street. See for example: Nation's psychiatric bed count falls to record low, Washington Post, 1 July 2016. "Researchers for the Treatment Advocacy Center, a national nonprofit organization, found that states' psychiatric bed total had fallen by 17 percent since 2010 – from 43,318 in 2010 to 37,559 this year." Etc.

[3. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Deinstitutionalisation ]

[4. What happened to U.S. mental health care after deinstitutionalization? Whashington Post 12 June 2013 ]

[5. From NRI-Inc.org: "Thirty-three years ago--in 1984--the NY Times listed the closure of state hospitals as a cause of homelessness and incarnation of individuals with Mental Illness." Link opens a 39 page pdf ]

Today, the man who suffers a severe mental illness has a far better chance of living outside a hospital than he would have had even a dozen years ago.

As recently as 1956 there were 335 patients in public mental hospitals for every 100,000 people in the USA. By 1962 there were 283 per 100,000, and today there are only 238. At the end of World War II there were 4,000 American psychiatrists. Today there are 22,000. Equally significant, a Joint Commission on Mental Illness, created by Congress and organised by the A.P.A. and the American Medical Association, has formally defined the goal of treatment of' major mental illness as keeping the patient out of a hospital and in his community as much as possible. Following the Commission's recommendations, Congress has appropriated $23 million for the construction and staffing of community mental-health centres, a concept which psychiatric organizations have endorsed with a unity unmatched in U.S. psychiatric history.

To qualify, an institution must plan to coordinate at least five basic, community-oriented services: (1) inpatient, or full-time hospitalisation; (2) outpatient services; (3) a day-care program of part time hospitalisation; (4) emergency services around the clock; and (5) a program for consultation with and education of local agencies and doctors. As of last April, 276 centres, covering 44 million people in 48 states and territories, had received construction and staffing grants totalling $146 million.

Yet for all its growth and its increased contacts with the community, psychiatry has really achieved only token integration. Most Americans still can't distinguish between psychiatrists and psychoanalysts, which is like thinking of all journalists as sports writers. Out of 16,000 members of the A.P.A., only 1,600 are psychoanalysts, and many of those use analysis in treating only a minority of their patients. In terms of appeal to public sympathy, mental illness itself still ranks far down – behind polio, tuberculosis, cancer, heart disease, crippled children, cerebral palsy and muscular dystrophy. Yet social attitudes often determine treatment. Dr. Menninger recently gave a succinct explanation for the strides his profession has made in recent years. "In my student days," he said, "they weren't supposed to get well."

Until very recently there was a strong tendency, in almost all psychiatry's approaches, toward treating mental patients as though they existed in a void. Since the mentally ill did not behave in normal ways, society removed them from the normal world. Once in an institution, the normal world ceased actually to be much of a factor in the patient's life, and he was treated without reference to it – if he was treated at all. If he recovered, he was replaced in the normal world and cut off from all contact with his asylum.

The Freudian model, on which most modern psychiatry is based, strengthened this isolating approach. Freud saw the adult as having an established mental system, which followed certain constant laws of its own. While he conceded the importance of current stresses in aggravating weak spots in this system, he concentrated his treatment on the weak spot itself, and never regarded the current stresses as something he could properly treat in analysis.

All the major developments in psychiatry in recent years have moved away from this approach, and they have come with the growth of the profession.

"We're a relatively new profession," says Dr. Francis Braceland, past president of the A.P.A. and current editor of its American Journal of Psychiatry. "It was only in the 'Thirties that there were any private psychiatrists. Before that, they were all behind walls."

"I was practicing here prior to World War ll," says Dr. Ralph Greenson, of Los Angeles, "and I would guess that there were only five or six psychiatrists of all kinds in all of Los Angeles. There were less than two hundred analysts in the United States. Analysis was considered shameful.

In the early days of the war, if a man broke down in combat and couldn't fly any more, he was tried for lack of moral fibre. Then, in the Eighth Air Force in England, it was found that even the most heroic men, after a certain number of missions, would get nervous convulsions and shakes and get drunk every night. With the realization that even the bravest man had a breaking point it even became fashionable to have combat fatigue."

More than half of all U.S. World War II casualties were mental, and by the end of the war millions of people had altered their concept of mental illness. Psychiatrists, seeing combat breakdowns rectified in 24 hours, had begun to re-evaluate the role of immediate stress in mental illness. A nation determined to take care of its veterans gave large amounts of money to the Veterans Hospitals. At the same time, society at large was deciding to attack all its problems, including mental illness, on a large scale. Federal expenses for mental-illness research shot from $1.5 million in 1950 (when the Federal Government spent $30 million for research on hoof-and-mouth disease) to $220 million this year.

Meanwhile English psychiatrists were getting good results with more liberal treatment of hospitalised mental patients. When locked wards were opened and the patients were given both more help and more responsibility, many stopped soiling themselves and destructiveness declined.

"One of the things we've learned is that there is a greater destructiveness in a pathological environment than in the illness itself," says Barney Stone, formerly head social worker at Colorado's Fort Logan Mental Health Centre.

"People developed asylum lunacy; they became hospital habituated. We found that if a patient got out of a hospital within one year, he had a 90 percent chance of staying out. After that first year, his chances were cut in half. After the second year, he was almost sure to be permanent."

The last and most critical factor in this dehospitalisation process was the new mind drugs of the 'Fifties, which calmed the most disordered patients and made them treatable by other means. One third to one half of all prescriptions written today are for mind drugs.

"With the drugs we have now, there should not be any more madhouses," says Dr. Sidney Cohen, who is associated with the Brentwood (California) Veterans Hospital. "We used to spend more damn money up at Brentwood repairing broken windows and stuffed toilets and broken light bulbs than I bet we spend on drugs now. Today's young psychiatrists, they just can't realize what it was like."

Today some hospitals still lock up all new patients, and most hospitals have some locked wards, but some, like Colorado's Fort Logan, do not lock any wards at any time. Furthermore, many more people than ever before are receiving psychiatric treatment while continuing to work, raise families, or otherwise partake of normal life outside a hospital – and much of this is thanks to the drugs. Just 20 years ago, a hospitalised mental patient named Lara Jefferson wrote in her diary:

"Here I sit – mad as the hatter – with nothing to do but either become madder and madder – or else recover enough of my sanity to be allowed to go back to the life which drove me mad."

If Lara Jefferson were a mental-hospital patient in certain states today, at the time of discharge she would be told to visit her local mental-health clinic, which would be advised she was leaving the hospital. She would be given a five-day supply of psychoactive drugs and a prescription for more, and if she didn't show up at the clinic with her prescription after five days, a public-health nurse would go to her home to find out why.

Even in the face of great obstacles, hospitals have managed to reduce their patient load. In 1963, when Dr. Charles Meredith became superintendent, the large and isolated Colorado State Hospital in Pueblo was revamping its program. In four years, with the help of a new state program, Dr. Meredith reduced the patient population from 4,000 to 2,100, and the average stay from 5 months to 3 months. Seventeen hundred geriatric patients have been sent home. "The whole trend has been reversed," he says, "and we have knocked five buildings down."

Incoming patients are now sent to a building designated for their part of the state, and the building's staff members know the area's judges, doctors, and social agencies. To reach people in remote areas, the hospital uses private psychiatrists who make their rounds by plane and are known as "flychiatrists." In the children's division, 16 children are living in small cottages with undergraduate psychology majors from South Colorado State College as counsellors. During the day the children and counsellors go to school and college in town, and in mid-afternoon they all return to the cottage. The experiment hopes to show that intensive therapy in a nearly normal selling can enable disturbed children to go to regular schools. "If it works," Dr. Meredith says, "the same system can be applied out in the hills, without any hospital plant at all."

Many psychiatrists are also working with doctors and ministers to enable them to take care of patients who are only mildly disturbed. A small, county-sponsored mental-health centre in Grand Rapids, Michigan, has found that the cost of actually seeing a family is 10 times greater than the cost of merely advising the family doctor, and most of the time the results are no better. Today 8 of every 10 families it deals with stay in the care of a local doctor or agency.

As a theoretical accompaniment to these changes, the profession has modified its thinking about what constitutes normality and to the point that many psychiatrists now question whether either word has any real meaning.

Psychiatrists have long noted that mental illness never seems to be total. Freud wrote that even patients with severe hallucinations later reported that "In some corner of their minds, as they express it, there was a normal person hidden who watched the hubbub of the illness go past like a disinterested spectator."

Recent experience has convinced most psychiatrists that mental health is also never total, and that the amount of health varies from time to time. One remarkable study of 175,000 people in New York City, excluding all those under 20 or over 59 and Negroes and Puerto Ricans, has suggested that the general level of illness is much higher than most people would like to think. The study found that 36.3 percent of the subjects had "mild" symptoms of mental illness, 21.8 percent had "moderate symptoms, 13.2 percent had "marked" symptoms, 7.5 percent had "severe" symptoms, and 2.7 percent were so disturbed that they were virtually incapacitated. Only 18.5 percent showed no signs of mental illness at all.

Such observations have convinced many psychiatrists that their proper study is not specific diseases like schizophrenia but the "whole" man who has developed a harmful way of reacting to his life and himself, and this view has led psychiatry to expand its area of concern. The Menninger Foundation's Division of Industrial Mental Health, under psychologist Harry Levinson, gives seminars to doctors and businessmen, and advises organizations on specific problems. In San Mateo County, California, about half the people sentenced to jail go to one of two "honour camps" run by the sheriff with the help of the county mental-health centre.

Psychiatry's rapid expansion, however, has given it some growing pains. The demand for psychiatrists is increasing even more rapidly than the supply thanks in part to the profession's efforts to convince the public that mental illness is curable and not shameful. Reducing the number of patients in a hospital moreover, often brings a cut in the hospital's funds. California's Governor Ronald Reagan, who once sent his dog to a psychologist ($245 for six sessions of therapy), cut $17 million from California's mental-health budget last year on the grounds that a reduction in the number of patients enabled the state to do without 3,700 mental-health workers.

More ominously, some hospitals have already built up a backlog of chronic patients who, in the standard phrase, "are unable to benefit from our treatment," and more custodial facilities may be needed for them. Some psychiatrists also think that the zeal for building new centres, in the words of Dr. David Vail of Minnesota, "is like hoping to cure illiteracy by building more libraries," and the community psychiatry movement has been accused of noisily overselling itself.

Whether or not this is true, many sections of the community have been slow to welcome psychiatry into their midst. The current relations between psychiatry and the clergy are generally uneasy. Fewer than 9,000 clergymen, or four percent of the country's total, have ever taken a course in clinical pastoral counselling, and the Academy of Religion and Mental Health, which was founded to bridge the gap between the two professions, estimates that fewer than seven percent of all clergymen have even an adequate knowledge of psychiatry.