SelfDefinition.Org

Practical Memory Training

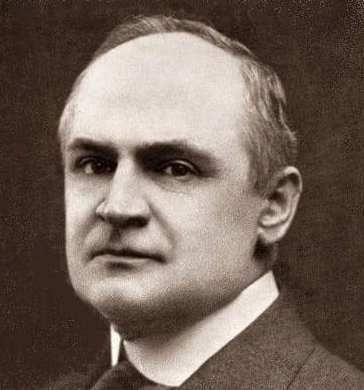

'Theron Q. Dumont'William Walker Atkinson

(1916)

Lesson 22 Efficient Association

Principle of Association

As I have repeatedly informed you, this great second principle of memory—the Principle of Association—plays a most important part in the process of recollection and remembrance. It is second only to the Principle of Attention. As the best psychologists have discovered, voluntary recollection is possible only when the memorized thing is connected with, linked to, or associated with other memorized things. The greater the number of such associations, the greater the probability of its recollection when required.

[James] Beattie [1] well sums up the matter when he says: "The more relations or likenesses that we find or can establish between objects, the more easily will the view of one lead us to recollect the rest."

[1. (1735-1803)

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/

[Neil] Arnott [2] says: "The ignorant man charges his hundred hooks of knowledge with single objects, while the informed man makes each hook support a long chain to which thousands of kindred and useful things are attached."

[2. Neil Arnott, MD, Elements of Physics, or Natural Philosophy (pub. about 1835) , Google Books Extract here: screencap.]

Others have advised that each idea be "entangled" by threads of association to many other related ideas, so that the recollection of one will bring to light the rest, if they are needed.

In the earlier lessons of Association, I have described the association of contiguity in time and space. Our present consideration is that of contiguity in consciousness, by relations of likeness, etc. For the reason that we have seen, we should endeavor to associate the thing to be remembered, with as many related and similar things as possible. Or, if you prefer this illustration, it may be said that we should endeavor to view them from as many angles—as many view-points—as possible. The more we know about a thing, the more easily is that thing recalled in memory.

Many elaborate schemes and systems of artificial association have been devised, and while each of them probably contains some ideas of merit the most of them are too cumbersome, artificial and strained to be of much practical use.

For instance, some of these systems teach long chains of words, each associated with the one preceding, and the one following it; the idea being that by memorizing these chains of words, one may travel along this course and recall the desired word. For instance, in some of these systems the following artificial and strained associations were taught—the examples are actually given in these systems, as amusing as they may seem to the student of rational memory training. Here are the examples—study them carefully, O, student; and see what you have escaped:

Example I. "Chimney—smoke—wood—tree—leaf."

Example II. "Pillow—feather—quill—pen—ink."

Example III. "Apple—windfall—windstorm—wrap well—Apfel."

The first two are so far fetched as to need no comment—surely one could connect Chimney and Leaf, or join Pillow and Ink, without this chain. As for the third, which is supposed to furnish an easy way to teach the English person the German word for Apple—this in the words of our American cousins, "is the limit." Does not Apple, itself, suggest Apfel, much more readily than this cumbersome chain? Surely the learning of a new language has sufficient terrors, without adding strange and frightful ones in the form of such a "system!"

Imagine trying to memorize a list of names or articles in this way! Such methods remind me of an attempt to reach London from Paris, by traveling eastward through Europe, Asia, the Pacific Ocean, through America, the Atlantic Ocean, Ireland, England, and thus at last reaching London, Hurrah! This may be a delightful trip if one has the time and money—but for ordinary purposes, I prefer the usual trip across the Strait of Dover, with its little railway journey at each end. Imagine trying to reach a point directly across the street, by deliberately turning your back upon it, and then traveling around the world in the opposite direction from it, with the idea of approaching it from the rear! These systems are equally as ridiculous, to my mind.

Before leaving the subject, I ask you to consider a few lines from a satire on these cumbersome systems of memory, which appeared in the magazines a few years ago. In the story, a man tries to remember the name of his sweetheart in this way, as per the "system" he has studied. Listen to him: "Girl—dress—dressmaker—sewing—thread—spool—cotton—cotton-mill—spinner—bobbin—bob—Rob—Robert—Roberta!" Roberta was the girl's name. Eureka!

The story, however, goes on to say that in time the young man fell in love with another girl, whose name he remembered as follows: "Girl—dress—dress maker—sewing—thread—needle—pins—Pinafore—Josephlne!" And thus he remembered his beloved Josephine.

The sequel is unhappy, however, He gets his associative chains twisted, and proceeds to address Josephine as "Roberta." Tableau! I do not think that you require any instruction of this kind, dear students. You may easily invent chains of this sort, to amuse yourselves, if you wish—but not for the purpose of memory training, I beg of you.

There are, however, a number of forms of artificial association, some of which may be applied at times, as "pegs" upon which to hang little bits of memorized things. I shall mention these in their proper place. At present, however, I think it better to proceed to a consideration of the best and most scientific methods of real, logical methods of efficient association. These methods are based on actual psychological principles, and are as real as the mind itself. They follow Nature's own laws, and are in the line of all real acquisition of knowledge by the use of the memory. An observance of these laws strengthens the mind and memory, instead of weakening them as do many of the extremely artificial systems, such as those I have just mentioned.

These methods of efficient association may be grouped into three general classes as follows:

- I. Analysis.

- II. Comparison.

- III. Synthesis

I shall now ask you to follow me in the consideration of these three great classes of association in memory. I shall point out the practical methods of application, of course, as we proceed. But you must know why you are doing a thing, as well as being told how to do it, if you wish to become reaIly efficient and proficient in the subject.

Analysis

ANALYSIS. Analysis may be defined as the process by means of which anything is resolved into its original parts, usually including the examination of such constituent parts. It is the dissection of a thing; the taking apart of its component parts; the setting aside of its properties, qualities and attributes. In short, it results in the examination of a thing's parts, and the perception of the thing as composed of these parts—rather than the perception of the thing as a solid whole.

It is axiomatic that we can know a thing more fully if we have analyzed it into its parts or qualities. And, it is equally axiomatic that the better we know a thing, the better do we remember it. Therefore, it is seen that by analyzing a subject, or object, which we wish to remember, we are taking the best steps toward impressing it upon the memory.

And, I need scarcely again remind you that by associating it in memory with its many component parts or qualities, we are making it easy for us to recollect it by means of the many associative "loose ends" of memory. In short, we are indexing and cross-indexing it very thoroughly in this way, so that we may find it catalogued in memory under many headings.

One of the leading principles of many modern "memory systems," is that known as "Interrogative Analysis." To listen to the glowing descriptions of this principle by some of the teachers, you might imagine that they had discovered this principle. But, as all students of the subject know, or should know, the principle is as old as the science of teaching, and its value has always been recognized by the best minds of the race. It was the keynote of the teaching method of Socrates, who was born 468 B.C.

Socrates taught philosophy by asking questions of his pupils, and thus drawing out their knowledge on the subject, and at the same time opening the way to the creation of more knowledge by stimulating the mind to activity in the direction of fitting out the idea of things which were outlined by his questions. It is noteworthy that the pupils of Socrates were also renowned for their excellent memories—just what might have been expected, when we remember the laws of association by analysis.

Interrogative Analysis

There have been many ingenious plans of interrogative analysis arranged by teachers, but many of them are too cumbersome for efficiency The best results are obtained by the more simple rules and methods. In its simplest form, interrogative analysis may be illustrated by the simple analysis of a verse, or Biblical quotation, which one may wish to remember. This process proceeds as follows using the familiar opening lines of [Sir Walter] Scott's "Lady of the Lake" as an example:

"The stag at eve had drunk his fill,

* Mispelling of Glenartney.

Where danced the moon, on Monan's rill;

And deep his midnight lair had made,

In lone Gletartney's hazel shade."

The interrogative analysis would proceed as follows:

Q. Who is the actor? A. The stag!

Q. When did he act? A. At eve!

Q. What did he do? A. (a) Drank, and (b) made his lair!

Q. Where did he do these things? A- (a) he drank from Monan's rill, and (b) made his lair in the shade of Gletartney!

Q. How, or in what manner? A- (a) he drank his fill, i.e., drank deeply and fully; and (b) he made his lair deep, for his night's rest.

This may be analyzed still further, if desired, as follows:

Q. Describe Monan's rill! A. Its waves were in motion, and the moon was reflected from its dancing waves!

Q. Describe the scene in Gletartney's shade! A. It was a lone, quiet, secluded place, and with deep shadows falling from its hazel trees, beneath the light of the moon!

From another angle, the analysis may he made as follows:

Q. What idea does each line convey? A. (1) The stag drinking his fill at eve; (2) the secne of his drinking—Monan's rill, with the moon dancing on its waves; (3) the deep midnight lair, made by the stag, following the draught at the rill; and (4) the scene in the lone shade of the hazel trees of Gletartney!

The mind can readily picture each of these ideas.

Try the experiment of first merely reading these lines aloud, and then reciting them slowly, with the above analysis in mind. You will find that the first recitation merely "scratched the surface" of your memory, whereas the second made a comparatively deep impression. In fact, it is extremely probable that you have impressed the lines themselves upon your memory, by simply making the above analysis, and mental picture. At any rate, you will remember the picture, clearly, and for a long time, from having merely made it once in this exercise. Try the principle on other verses which may occur to you—the following from Ella Wheeler Wilcox, for example;

"Laugh, and the world laughs with you;

Weep, and you weep alone!

For this sad old earth

Is in need of mirth—

It has troubles enough of its own."

In the same way, the favorite method of Biblical verse analysis has proved of the greatest assistance to many clergymen and priests have followed ft. Apply this method to the following quotation:

"For God so lived the world, that he gave his only begotten son, that whosoever believeth in him shall have everlasting life."

Q. Who? A. God!

Q. What? A. He loved!

Q. He loved what? A. He loved the world!

Q. How much did he love the world? A. So much that he gave his son!

Q. What son? A. His only begotten son!

Q. For what purpose did he give his only begotten son? A. That whosoever believeth in him shall have everlasting life!

Q. Who should have everlasting life? A. Whosoever that believeth in him!

Q. What kind of life? A. Everlasting life!

Q. Why shall whosoever that believeth in Him have everlasting life? A. Because God gave his only begotten son for that purpose!

Q. Why did God so give Him? A. Because he so loved the world!

Now re-read the verse in the light of the analysis, and see how much clearer it is in the memory and understanding, than before.

I know of no better, simpler system of applying the above principles of interrogative analysis, than the familiar set of questions to be so applied, as follows:

The Seven Questions

(1) Who?

(2) Which?

(3) What?

(4) When?

(5) Where?

(6) Why?

(7) How?

The two first questions bring out and establish the identity of the person or thing; the third brings out the action to or by the person or thing; the fourth and fifth, the place and time, the sixth the reason or purpose, and the seventh the manner of the action.

This apparently simple code of questions will bring out a wealth of detail regarding any event, person, or things, and will serve to fix it in the memory as a more clearly understood thing. Each question is the key to a host of associative impressions. I again remind you that the use of a pencil in noting down the information that you draw forth from yourself in this manner, will aid you materially in this work.

Higher Analysis (Gurdjieff's list)

HIGHER ANALYSIS. There have been designed a number of tables, or systems of higher or fuller analysis than the Seven Questions, all operating on the same principle. The following is the one which I have adapted, and used in my personal class work here in Paris. It answers the purpose better than any other form I ever have employed: [1]

[1. Part of this list appears in Chapter 9 of Views from the Real World, compiled by students of Gurdjieff. /gurdjieff/real-world/ch-09-constitution-and-how-to-think.htm ]

(1) Name of Person or Thing?

(2) When did it exist?

(3) Where did (or does) it exist?

(4) What caused it to exist?

(5) What is its history?

(6) What are its leading characteristics?

(7) What is its use and purpose?

(8) What are its effects, or results?

(9) What does it prove or demonstrate?

(10) What is its probable end or future?

(11) What does it most resemble?

(12) What are its opposites?

(13) What do I know about it, generally, in the way of associated ideas?

(14) What is my general opinion regarding it?

(15) What degree of interest has it for me?

(16) What are my feelings regarding it—degree of like or dislike?

This system will bring out of your mind a surprising volume of information, and will also serve to impress the thing firmly and clearly upon your memory by hundreds of associative links. Prove this by applying it in earnest, and you will perceive the principle and realize its possibilities.