SelfDefinition.Org

Practical Memory Training

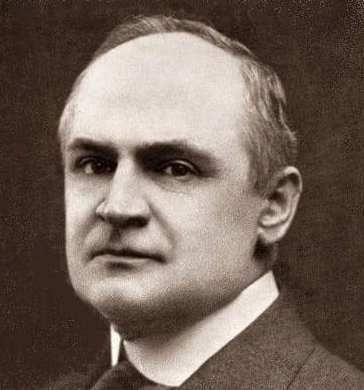

'Theron Q. Dumont'William Walker Atkinson

(1916)

Lesson 25 Efficient Recollection

[Pages 237 and 238 are missing in the scan. Page 239 continues...]

... We may recall an idea, and recognize its relation to other ideas, but at the same time may not be able to recall the book, or place, from and in which we first perceived the idea or thought. Full identification covers all the other factors and may be considered as a full recollection.

I have pointed out that remembrance may be considered as involuntary recollection, awakened by some subconscious process, or perhaps by some association with something just perceived. In such cases we did not try to recall the idea—did not even desire to do so. Many remembrances may come to us unasked, and alas! too often, undesired and undesirable. Recollection, on the other hand, is purely voluntary, and comes as a link in a chain of memory processes set into operation by an act of the will. Sometimes the idea is recalled immediately, or shortly after we have called for it, by an act or demand of will. At other times, it does not appear for some time afterward, and perhaps after we have given up all hope of recalling it. Every one knows how these half-forgotten ideas will flash into the consciousness, after having been "given up."

Psychologists who are familiar with the operation of the subconscious planes of the mind know that the latter often will bring to light impressions of this kind, in response to a firm, confident command to it to perform this work. Strange as it may appear, the mental command "Here! memory, find this thing for me—and bring to me as quickly as possible!" will act in the direction of setting into operation the subconscious machinery of reproduction of impressions. In many cases, in a few minutes the thing will flash into consciousness. In such cases, it is well to turn the mind to something else, giving up the conscious search, and trusting entirely to the subconscious to do the work for you. Of course, the words of the command have no magic in them, and are merely used for the purpose of giving the voluntary command properly. Try this experiment on yourself, and see how soon it will begin to work out successfully.

While the succeeding lessons of this course will have much to say regarding the application of the principle of recollection to various forms of memory reproduction—in which the principal points will be brought out in various ways—there are, nevertheless, a few general rules and details which should be touched upon at this point. I now call your attention to the same.

In the first place, there is much in the mental attitude you assume toward your memory. If you doubt and distrust it, your subconsciousness will be apt to take up this idea and make it come true in practice. If, on the contrary, you assume an attitude of trust and confidence in your powers of recollection, your subconsciousness will take up the idea as true, and tend to make it come true. This is not "faith cure," or any thing of that kind, but is based on true psychological principles. There is more in the great psychological Law of Suggestion, in these matters, than the average man has any idea of. Do not lose time trying to explain this thing—some other time will be as well—but put the principle into practice, and notice how well it works out for you.

Again, in trying to recall an idea, or impression, if you cannot get it at once, and easily, try to find the "loose end" of association, and recall it in this way. Try to remember something that you heard or saw at the same time or place, and you will often find your "loose end" without more trouble. Or, else think of something else that resembles it in some way, or else is very different from it. Try to find it by any of the different phases of association of which you have been told in these lessons. The thing surely has a number of associations in your mind—try the most likely ones. Try to recall it by eye-memory, and ear-memory, in turn. If you have mastered the principle of association, you will generally manage to get hold of some associative "loose end." In this connection, it may be well for you to try to recall the memory of the last time you recalled the thing in memory—this often will bring the thing into consciousness, for you will have set up some form of associated time impression which will help you out.

And, in this last connection, whenever you recall a thing in this way, remember what particular "loose end" helped you out. The same thing will probably act the same way the next time, and by remembering the helper you have created a strong associated element for future use. And, again, also try to send a recalled impression back to the memory, when you are through with it, with a strong, fresh perception, and with as many good strong- logical associations as possible, for this will help you to recall it later on. Remember, also, the principle that impressions deepen and grow stronger by each recollection—each re-perception gives strength and depth to the original impression. Finally, in recalling an old impression, endeavor to recognize and identify it as fully as possible, for by so doing you give it stronger associate value, both as concerns itself and also the things so associated with it.

Another useful point in this connection, is this: if you cannot recall a thing, do the next best thing and try to recall some component part, phase, or aspect of it—this often brings to consciousness the missing parts, by the operation of the law of association. For instance, if you are trying to remember a scene in London, and cannot bring it clearly into mind, try the experiment of recalling to mental vision of some other London scene as close to the wanted one as possible. In a moment or two, the association is apt to bring you the desired recollection.

If you cannot remember the features or name of one member of a family, try to recall the appearance or name of some relation or friend of his, and you will often set up the chain of association in this way. Again, if you forget a name, try the experiment of running over the letters of the alphabet, slowly, and when you reach the right letter, the rest of the name will be apt to "pop out" in consciousness. If the name originally was merely heard, repeat the letters aloud; whereas if you originally have seen it in print, or writing, run over the alphabet in this way—the one arouses ear-memory, and the other eye-memory. If you have forgotten a locality or direction, try to travel over the original route in your memory, and you will soon get the missing place or direction.

Along the same lines, you will find it an aid to recollection, if you will place yourself, in imagination and memory, back in the same place and time in which you received the original impression. This will often set up associative memories which will give you what you want. Again, when you cannot recollect a thing, search for it in the class of memory associations in which it should have been placed. In such cases, you will find that, even though you have failed to give the thing its proper associates, nevertheless, it will have picked up certain of such associations, unconsciously and automatically.

The subconscious mind has a little trick of this kind, and often forms a set of associations for a thing even though we do not consciously seek to create them. In such cases, the association is made automatically, with some thing subconsciously remembered, although not consciously recollected. There is a twilight region of the consciousness in which work of this kind is often performed. So it is a pretty safe rule to look for associative links where they should be found even though you have not consciously placed them there. A good nut-shell rule covering the above various suggestions regarding the "helping out" of your power of recollection, is this: Reverse the process of Association—think of as many things bearing some possible relation to the thing you wish to recall, and try to get hold of the "loose end" in this way. In association you seek to "entangle" a thing in as many associations as possible; while in the case of a forgotten thing, you should seek to disentangle it from some of a number of possible or probable associations. Like a misplaced book on the shelves of a library you may often find the missing thing "somewhere around" the place where it ought to be.

If you can only resurrect some train of thought, or chain of associated ideas, in which the missing thing has ever appeared—the thing is as good as found, for all you will have to do is to pull on the "loose end" so furnished, and the thing will sooner or later appear.

At the last, then, "forgetting" is seen to be not the actual disappearance of the thing itself—for it is there in the subconsciousness, all safe and sound—but rather a loss of the "loose end" of the chain of which it forms a part. Every thing in the memory forms a part of many chains of association—the more associations you have given it, consciously or unconsciously, the more chains is it connected with. Or, putting it another way, the greater number of cross-indexes of association you have given it, the greater number of possible index cards on which you will find it printed, and the greater your chances of finding it.

I have told you all of these things about association, under that classification of the subject. But I am telling you them again, so that you may apply the REVERSE process, in case of a thing apparently lost to recollection. Just as you may associate a thing in order that it may be easily remembered and recalled, so you may hunt for things with which it may be, or should be associated, in hopes of finding one with "which the connection and association really has been made, consciously or unconsciously. Do you get the idea? Look for it in the places of possible or probable association, rather than conducting a blind haphazard hunt, or else giving it up in despair. Every thing has its right place, and this lost (?) thing may be in the right place, even though have not consciously put it there. The "little brownies of the mind," as Stevenson called them, may have done some good work for you, while you slept.