SelfDefinition.Org

Practical Memory Training

'Theron Q. Dumont'William Walker Atkinson

(1916)

Lesson 10 The Subconscious Realms

The recent discovery, by modern psychology, of the great field of subconscious mental activity, has attracted the attention of both science and philosophy. It has been the missing link which now serves to weld together the hitherto loose ends of many facts regarding human personality and the powers of man. One of the principal points emphasized by this new understanding of the mind, is that man is much greater than he has thought himself—that the little conscious area that he has called the Self is but a tiny point on the great body of Self—that man has many powers and energies, available for his use and awaiting his call upon them. Some of the greatest minds of the day have expressed themselves forcibly regarding this great subject. It becomes the duty of every thinking, progressive man, striving toward increased efficiency, to acquaint himself with these new ideas, and to place himself in the new current of human thought.

Dr. Schofield, the eminent English scientist, has expressed this idea in the following beautiful words: "Our conscious mind, as compared with the unconscious mind, has been likened to the visible spectrum of the sun's rays, as compared to the invisible part which stretches indefinitely on either side. We know now that the chief part of heat comes from the ultra-red [infra-red] rays that show no light; and the main part of the chemical changes in the vegetable world are the results of the ultra-violet rays at the other end of the spectrum, which are equally invisible to the eye, and are recognized only by their potent effects. Indeed, as these visible rays extend indefinitely on both sides of the visible spectrum, so we may say that the mind includes not only the visible or conscious part, and what we have called the subconscious, that which lies below the red line, but also the supra-conscious mind that lies at the other end—all those regions of higher soul and spirit life, of which we are at times, vaguely conscious, but which always exist, and link us on to eternal verities, on the one side, as surely as the subconscious mind links us to the body on the other."

This quotation naturally leads to the well-known statement of Sir Oliver Lodge, the celebrated scientific authority, of international fame and standing, in which he tells the world of thinkers to: "Imagine an iceberg glorying in its crisp solidity and sparkling pinnacles, resenting attention paid to its submerged self, or supporting region, or to the saline liquid out of which it arose, and into which in due course it will some day return. Or, reversing the metaphor, we may liken our present state of mind to that of the hull of a ship submerged in a dim ocean among strange monsters, propelled in a blind manner through space; proud, perhaps, of accumulating many barnacles of decoration; only recognizing ...

[Page 91 is missing from the scan. Continuing with page 92 ...

...tion, or missing idea, flashes into consciousness like lightning from a clear sky.

In some cases of this kind, eminent persons have stated that the answer came so unexpectedly that it almost seemed as if it had been superimposed upon the mind by some high authority. It is no wonder that the ancients believed that each man of genius has "genii" who supplied him with ideas in this wonderful manner. But modern science now knows that it is the man's own mind which does the work, though the work is performed on planes below the levels of consciousness. Further investigation reveals the fact that so far from this being the exception, it is a most common fact. Really, it is deemed probable that at least eighty per cent of the mental work is performed on the subconscious planes of the mind; and this includes some of the highest processes of reasoning.

That the above related mental phenomena belong to the same category of mental activity as do the phenomena of memory, is evidenced by the very familiar incident of one being unable to remember a certain fact, and then, after having been "given up," the missing idea will suddenly burst into consciousness, often bringing with it a train of associated ideas. Moreover, who of us is not familiar with the uncomfortable sensation of something which ought to be remembered—something to be done, said, or thought of. Conscious effort seems to bring no results in such cases, at times, and we are apt to give the thing up in disgust, and to turn our consciousness to something else, when, all of a sudden, apropos of nothing whatsoever, the missing thought will flash into our conscious field, and all will be well. There is often a sense of mental and physical relief when this is accomplished, as if the brain has accomplished a bit of hard work.

In the same way, we often perform the primary work of a line of thought, in our conscious mind, and then lay the matter aside, either from weariness or else to attend to other work. After a time, sometimes quite a long time, we turn our attention again to the matter, and lo! we find that the subconscious mind has been at work on it, and that the intermediate steps have been taken, the result being that we have merely to add the finishing touches and polishing up work. Can any one question the fact that the subconscious work was as truly mental activity as was the conscious?

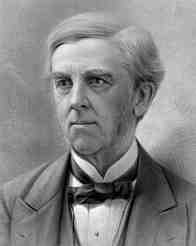

Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr. (1809-1894)

Oliver Wendell Holmes, the celebrated American writer, has well told us that: "There are thoughts that never emerge into consciousness which yet make their influence felt among the perceptive mental currents, just as the unseen planets sway the movements of the known ones. I was told of a business man in Boston who had given up thinking of an important question as too much for him. But he continued so uneasy in his brain that he feared he was threatened with palsy. After some hours the natural solution of the question came to him, worked out, as he believed, in that troubled interval."

I think it very probable that the sense of having done wrong, and the feeling of regret that comes to us became of our having "left undone the things that we ought to have, and done those things which we ought not to have done," [1] which we generally ascribe to "conscience" is really a phase of subconscious activity. That is to say, I do not deny the fact of "conscience"—for all have experienced its reproaches—but I believe that it has its seat and field of work in the great subconscious region of the mind.

[1. Book of Common Prayer.]

Very few of us realize how much we are dependent upon the work of the subconscious-memory activities, in our ordinary work of thinking, deliberation, and consideration of a subject. Analyzing the processes of this mental work, we see that we first consider one idea or fact, and then, without any conscious effort on our part, an idea closely associated to the first one comes into our mind—from where? Then flows a steady stream of thought, fact following fact, idea treading close upon the heels of ideas. Where have these facts and ideas been stored? In the subconscious memory of course. What processes keep them flowing, when once started by the conscious attention? The subconscious processes, of course? Do you not see how closely the subject of memory and subconsciousness are related, and how important both of them are in the processes of thought?

There is under way in the most of us a constant process of subconscious mental digestion and assimilation, of which we are quite unaware until time and circumstances bring into consciousness the work thereof. We have certain views and opinions regarding certain things. We listen to opposing views, ideas, and opinions, and they seem to make no conscious impression upon us. But, at some time we feel called upon to express our opinions on the said subjects, and, strange to say we find ourselves holding an entirely new view, often contrary to the former one. Though we were unaware of it, our subconscious mind took in the new ideas and arguments, views and opinions, and digested them carefully, assimilating the result in subconscious judgment, and surprising us with the compacted result when we start to fix our attention on the subject. We are apt to say that our "feelings on the subject have changed," but it is more than a matter of "feeling"—it is a matter of changed opinion and judgment, thought arrived at subconsciously.

Even the old psychologists freely admitted that our feelings and emotion operate below the plane of consciousness, but they were loath to admit that any processes of logical thought were so performed. But modern psychology draws no such distinction. It recognizes the great work performed on subconscious planes in all mental operations, and all forms of mental activity whether those of feeling, those of willing, or those of thinking. Modern psychology recognizes the presence and power of subconscious feeling, subconscious will, and subconscious thought—in fact, it claims that the greater part of each and all of these three great classes of mental action is performed below the plane of the ordinary consciousness.

Some authorities who have given great thought to the subject, claim that the subconscious mind (as they call it) will reason with absolute logical sequence and accuracy from any premise strongly impressed upon it as a fact, and will bring the process to an absolutely logical conclusion if allowed to work without interference from the conscious mind. That is to say, the subconscious faculties will apply the strict rules of logical operations, to any premise so presented to them, under the proper conditions. The answer may not be true, but it will be technically correct, according to the laws of logic, providing the premise is assumed as correct. A false premise can produce only a false conclusion, of course. I mention this, in passing, merely for general information. I do not insist upon its correctness; in fact I think that the matter is still open to discussion, though the evidence, so far, seems to support the view advanced.

In imaginative work, the subconscious plays an unquestioned part. The representative faculties of imagination draw upon the subconscious mentality for their material, and their combination of memories into new groups. Many great writers freely acknowledge their indebtedness to the subconscious work of their mentality. R. L. Stevenson, tells us that these faculties:

"... do one-half of my work for me when I am fast-asleep, and in all human likelihood do the rest for me as well, when I am wide awake and foolishly suppose that I am doing it for myself. I had long been wanting to write a book on man's double being. For two days I went about racking my brains for a plot of any sort, and on the second night I dreamed the scene of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde at the window; and a scene, afterward split in two, in which Hyde, pursued, took the powder and underwent the change in the presence of his pursuer."

Many writers, composers, and inventors, have received inspiration in their dreams, which they afterward put into material form with great effect. In the dream state, of course, the ordinary consciousness is entirely stilled by sleep, leaving the subconscious faculties full play if they choose to work out problems for their owner. In the same way, persons have arisen in their sleep, and have written wonderful poems, stories, legal opinions; worked out problems in milhematics; composed music, etc., all without any conscious realization of what they were doing. These are extreme cases, of course, but they serve to illustrate the activities of these wonderful planes of the human mind—the great subconscious mentality.