SelfDefinition.Org

Practical Memory Training

'Theron Q. Dumont'William Walker Atkinson

(1916)

Lesson 12 The Law of Association

[Pages 106 and 107 are missing in the scan.]

[Lesson 12 picks up on page 108 ...]

... the "stream of thought," cannot flow. From this recognized principle has grown that great principle of memory, i.e., that the greater the number of associated impressions attached to an idea, the greater the probability of the recollection of that idea. Theoretically, if there were in your mind an idea absolutely detached from, and unassociated with other ideas, then that idea would be forever lost to you, for no matter how strong the impression, you would never be able to pull a "loose end" of associated ideas and thus bring to consciousness the lost idea. Consequently, all efforts in the direction of memory training or culture must take into consideration this great principle of the mind—association.

In order that you may fully grasp the paramount importance of this principle of association of ideas, I ask that you take a general glance at the processes of thought, and thus perceive the ever present principle at work. The uninstructed person is accustomed to the idea that his thoughts come and go without regard to law or order, and by mere "chance." But, here as everywhere else in Nature, we learn to realize that there is no such thing as chance and that everything is under the rule of law and order. The most idle, fleeting thought comes wholly because of previous associated thoughts or ideas—without these preceding ideas it would not have come, and could not have come. The law of the order and sequence of ideas is as regular and invariable as is the law of gravitation, the rise and fall of the tides, the rotation of the planets. Though we may not always be able to trace the associated ideas, we know that they must be there.

By this it is not meant that there is always a conscious precedent to an idea or thought. Rather, the greater part of the mental preceding ideas are below the plane of consciousness. But, as a rule, we can always find in consciousness a trace of the preceding current of thought which brought into consciousness the particular idea before us at the time. The recognition of this great law of psychology has brought that science into line with that of physics. We now realize that the mind, no less than the physical world, is under the influence of Law—that a universal law pervades everything, and that if we discover the natural principles we may take advantage of them and set them to work in our service.

Novelists, and dramatists, have taken advantage of this law of the mind, and have made their characters act in accordance therewith, the explanation being accepted by all readers or hearers as quite in accord with human experience. For instance, an old judge picks up a letter bearing the faint odor of mignonette, whereupon his memory carries him back in imagination to the scenes of the past, in which a certain fair lady played an important part. The missing link is supplied by the fact that the lady always used this particular kind of perfume. Or, again, the sound of a few bars of an old song, or other piece of music, will bring up thoughts and recollections of other scenes, persons, and incidents. Often a long train of thought is started in this way.

Poe makes one of his characters very expert in deducing the ideas in the mind of a person, by tracing up the train of association from a preceding remark, sight or sound. It is an interesting experiment for one to stop at some particular point in a long train of thought, and then, step by step, work his way backward along the line of thought. One, usually, is greatly surprised to discover what a far cry it is from the first idea to the last. Recognizing this principle, it is at once perceived how much broader is the thought of a person whose ideas have a wealth of associated ideas, as compared with one whose ideas have but few links of associated thought. As startling as it may appear, it is a fact that in this difference in degree of association of ideas, is found the secret of the difference between an educated man (in the true sense of the term) and an ignorant one.

The phenomena accompanying the manifestation of the psychological law of Suggestion [1] (of which so much is heard in these days) are due largely to the operation of the principle of association of ideas.

[1. See on this site: The Law of Suggestion (1902) by James H. Loryea, a.k.a. "Santanelli" ]

That is to say, it is found that a person generally associates certain facts with other facts and instinctively expects to find the second following the first. If a hypnotic subject is made to believe that a piece of wood is a piece of heated iron, his excited imagination will naturally cause him to feel the sensation of heat when the counterfeit hot iron is applied to his flesh. The idea of burnt flesh is associated with the idea of hot iron, in his mind, and he acts accordingly.

In the same way, the impostor assumes the garb of a preacher, or Quaker, knowing that people usually associate honesty and fair dealings with that garb.

Many a shallow individual has gone through life with a reputation for being wise, simply because he had the facial expression and appearance of a thoughtful person—the only chance of discovery being that he would talk too much and thus discover to others his ignorance. The quack and charlatan have as their stock in trade a grave, profound expression, and a habit of saying as little as possible on any subject of real importance—a few sweetened words, platitudes, and generalities, accompanied by a "thus saith the Lord!" expression, is generally sufficient to create and maintain the impression of great learning among the uninformed and ignorant. All students of suggestion realize the great suggestive effect of associated ideas; and alas! the rascals are quick to avail themselves of this knowledge of psychology.

There are a number of laws, and minor principles, connected with the general law or principle of the association of ideas. The student will do well to familiarize himself with the same, for by so doing he will be laying the basis of an intelligent application of the power in the perception and filing away of his memory records in the great subconscious storehouse. I invite your attention to these laws and principles, in the following classification and analysis:

THE TWO GREAT CLASSES OF ASSOCIATION.

There are two great classes of association of ideas, viz: (1) association of contiguity; and (2) association of similarity. In the first class, that of association of contiguity, we find the ideas or impressions linked or connected with each other by reason of relation in time, space, etc. For instance, we remember an action as associated with the one which immediately preceded it, or followed it in time; or a thing as associated with the things adjoining it in space. Each impression is found to be one of a chain of this kind. We are able to reach one link by getting hold of another link in its associated chain. In the second class, that of association of similarity, the link is not that of sequence, but of resemblance to other things. In this class we find things of a kind gathered together in classes, subclasses, etc. We shall see this distinction more clearly as we proceed.

CONTIGUITY. The association of contiguity is more familiar to us than that of similarity—it is the more elementary form of association, and one that is manifested by the simplest and most uneducated mind. There are three forms of association of contiguity, as follows: (a) contiguity in time; (b) contiguity in space; and (c) contiguity in consciousness. Let us now consider these three forms.

CONTIGUITY IN TIME. In this form of association by contiguity, the impressions or ideas are linked in the order of their sequence in time. That is to say, our memories store them up in the same order in which they were originally ...

[Page 113 is missing in the scan. Page 114 continues...]

Many verses may be memorized and repeated in this way, but it is much more difficult to begin in the middle, or any other place than the beginning. If one wishes to remember a list of things to be bought at the shop, he will find it easier to make a regular list of them in his memory like the letters in the alphabet. By repeating this list, mentally, several times the memory of the first will recall the others until the end is reached. Children and servants instinctively recognize this principle, and apply it in remembering messages and orders given them. This form of association is like a string of beads—memory will pull one bead after another from the string.

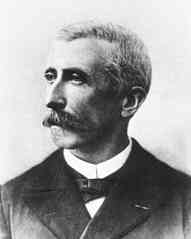

Théodule-Armand Ribot (1839-1916)

Psychology informs us that there is a very good reason for this ease in remembering things in regular sequence. It is not a matter of simple happening or chance, but rather the result of an established law of the mind. This law may be understood by reference to the following words of Ribot: [2] "When we read or hear a sentence, for example, at the commencement of the fifth word something of the fourth word still remains. The end of the fourth word impinges on the beginning of the fifth." Instead of a series of actually separated minute pictures, our mental moving-picture film is found to be rather a series of minute pictures, not actually separated from each other, but rather blending into each other and forming a part of that which went before, and that which comes afterward.

[2. Théodule-Armand Ribot

en.wikipedia.org/

Halleck points out this fact, by his illustration of the ignorant person on the witness stand, who must tell his story in his own way, or else he is unable to express himself. He says of the man: "If, between two given events, he bought a barrel of flour on trust at a red grocery, one of his children was teething, or he blew his nose, he must relate the events in the order in which they occurred. Having never learned to think logically, he really has no other way of getting from the one event to the other, except by using everything that happened as a stepping stone wherewith to cross the intervening stream. Deny him the right of using a certain stone, and he stands puzzled in mid-stream." [3]

[3. Ruben Post Halleck, Psychology and Psychic Culture, (1895) page 122, very large file: PDF, 373 pages, 21.5 Megs, at iapsop.com Also at

babel.

Every reader will recall some person who, always tells his stories in this way, with a plentiful sprinkling of "sez I," "sez he," and, many a side-trip into inconsequential by-paths of the tale. Listening to such a tale, told by such a person, we feel inclined to bid him, in the words of the slang of our American cousins, to "cut it out" of his mental film roll. An unscissored film results in a story long drawn out, stale and full of uninteresting details. Such cases serve to illustrate the psychological principle, however, and thus have their place and value.