SelfDefinition.Org

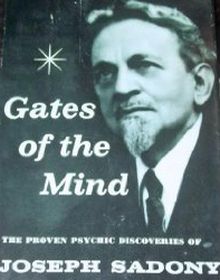

Gates of the Mind

The Proven Psychic Discoveries of

Joseph Sadony

Chapter IV

As a young man I began to visit all the various denominations of churches in the city, and to investigate all forms of religious belief and worship.

There were many questions that I wished to ask, but hesitated to state because I did not want to appear unduly inquisitive. I soon discovered, however, that if I asked these questions "mentally" (i.e., in my own mind without putting them in words), I would receive the answer in one way or another, during a conversation or discourse of the ministers or speakers.

I experimented with this for a while, without anyone knowing what I was doing. I received such strange and direct answers to my mental questions that I was led to experiment in having others ask silent questions of me.

The procedure was to start a conversation with the understanding that my questioner was only to think his questions; to talk about anything he pleased, but never to state the question he wished answered. Afterward we would compare notes; and I discovered that it was often easier to answer these unspoken questions than it was to answer questions put directly into words. Moreover, my answers to nine out of every ten questions were correct. What was functioning here?

In the first place, not knowing the question, my part of the conversation was spontaneous and without constraint or concentration of effort, as was the case when faced with a direct question that I was expected to answer in the same direct manner.

In the second place, at no time did I make an effort to discover what the question was, either by questions on my part or an effort to "sense" it or "read the mind" of my questioner. I refrained from this for the simple reason that when I tried it I was obliged to "think about it," and my best chance of success was not to think about it at all.

Consequently I never knew when or if I had answered the question until it came time to compare notes on the result. I would say or talk about whatever popped up in my mind during the conversation. More often than not it was something entirely foreign to the conversation; and consequently more often than not I really didn't know what I was talking about at all.

This was the origin of a deliberate effort on my part to apply the principle of "effortless thought without thinking" on an experimental basis.

* * * * *

The result of these early experiments, however, gradually got me deeper and deeper into a situation from which I was later able to extricate myself only by the drastic means of leaving the city and seeking seclusion. Word got around all too quickly that all a person had to do to get the answers to all his problems and troubles was to have a little talk with me.

At first I was glad enough to have people come to me, without my having to go to them, to carry on my experiment. It gave me a chance to learn a lot about human nature, human thinking, and the troubles and problems of the people at large. Moreover, it gave me a chance to practice and further develop the rather unusual art of "talking without thinking." Now, instead of being obliged to depend entirely on "images," I began to gain a greater facility in drawing on "words" in response to my "feelings."

But the less fortunate side of this experience, so far as I was concerned, was that as many as one hundred people per day, often more than that, would come to the place where I lived. This began to consume all my strength and time, so that it was difficult to earn a livelihood; and I would not "commercialize" what I felt should be held "without money and without price." Further, many of the people who came to me were poor and in need, with real trouble and problems of life beyond their capacity to solve them for themselves.

Also, the main requirement for my success in helping them was a sensitive, sympathetic attitude on my part, to which I submitted to such extent and their troubles were my troubles. I became bound to them. I could not refuse them what comfort I could give. And I shall never attempt to describe what I suffered as a consequence of this; sweating with them, shedding tears with and for them; keeping my nerves almost raw so that I would not fail them; praying for help, if help could be had from any "higher power," so I could meet these demands.

From a casual experiment I was plunged over my head into he midst of human woes, with people by the hundreds looking to me to relieve them from those woes in a world where war had taken toll again and where charlatans had risen by the score, of all types, to deceive them.

* * * * *

And still further, advantage was taken of me at every turn. Many came to me out of curiosity alone. I had not then developed resistance to this, and did not like to offend. So when businessmen came to me with their trouble, I was often drawn into considerations with regard to which I was not prepared by experience to understand the real issues involved.

For example, as the time drew near for another presidential election in 1900, William McKinley was nominated for re-election on the Republican ticket, with Theodore Roosevelt, then governor of New York, as vice president. William Jennings Bryan was nominated for president on the Democratic ticket, and there were a number of other minor parties, each with a candidate for president.

For a reason I did not at first understand, the outcome of this election was considered to be "crucial" by many businessmen, officials of various corporations, and one in particular (within the circle of my "friends and their friends"), J.W.A., who was a member of the board of Trade In Chicago. The subject came up continually in conversations as the elections drew near and for the first time in my experience I found myself being drawn outside of purely personal considerations into the whirlpool of national politics and affairs.

For the first time, too, I found myself wondering about these things. For this would be my first experience in voting as a citizen of the United States. At the time of McKinley's first election in 1896 I had been only nineteen years old, and it was only in 1898 that I attained my majority of derivative citizenship due to the naturalization of my father before his death, when I was a minor.

So now I took the matter of voting seriously, and wanted to know whom to vote for, and why. But the issues of the election were confusing. From all I knew previous to that time, they should have depended largely on questions of principle and policy in dealing with the colonial possessions that were taken from Spain in the Spanish-American War. There were questions of believing in war or not believing in war, of the liberties and treatment of peoples, of the principles of democracy, the spirit of the Constitution of the United States and American ideals in general.

But now there was talk of a monetary question again. That had been an issue in the 1896 election. The Democratic party had sought to introduce a silver standard and the Republican party, taking a stand for the gold standard, had won out. The result of this election in subsequent legislation should have settled the matter, and everyone thought it was settled. Even the Democratic party was willing to regard it as settled and concede their cause as "lost." But Mr. Bryan, as the Democratic nominee, insisted on raising the issue again. As a result of this there was an unexpected confusion in the minds of those who took their responsibilities of citizenship seriously.

Many who favored Mr. Bryan's views against militarism and existing colonial policies, and who were also in favor of his concept of a Christian Americanism, could not, for practical and economic reasons affecting their private interests, favor his proposal for a silver monetary standard.

Many who felt it necessary to support the Republican view in regard to the gold standard did not approve of what they called "the greedy commercialism" that dictated the Philippine policy of the Republican administration.

The result was that there were many in both parties who could not wholly approve of either candidate. As a consequence of this there was great apprehension in the commercial and industrial world with regard to the probable outcome of the election. And into this confusion of issues and uneasiness of spirit I was drawn through the instrumentality of friends and those who sought to take advantage of my mental experiments.

What immunity I might have had through my own concern as to how I should vote in this, my first election; though I had nothing personally at stake, no matter what the outcome might be. In the first place, I was aware that this time, because of the confusion of issues, many would not vote at all. I considered doing the same myself; but then I reflected that it would not be a good way to start my career as a citizen. I asked myself the question, "Is the majority always right? Do the people make the best choice?"

* * * * *

Suddenly I discovered that I wanted to know who was going to be elected. I had never asked myself such a question before, as a mental experiment. But now I did, I "blanked" my mind and turned my imagination loose to catch the answer from my "feeling." The result was a mental flash of a newspaper headline bearing the name of McKinley and containing a figure somewhat in excess of half a million majority. So I felt that while I was in no position to judge the issues on the little knowledge I then possessed, I would assume that the majority were right, and vote for McKinley.

If that had been all, this book would probably never have been written, and the whole future course of my life and thoughts would have been changed. But it was not all. In the course of my conversation with a number of businessmen, including the above-mentioned J.W.A., when they asked me questions concerning the coming election, I forthwith answered now what I had never been able to "feel" in their presence, that I thought McKinley would be elected by about half a million majority.

I do not recall any special reaction to these conversations except in the case of J.W.A. Upon that occasion, however, I experienced a phenomenon that was new in my life. After predicting to him the outcome of the forthcoming election, I became suddenly confused, and felt a sense of panic and shock followed by such a feeling of depletion, shame, and dejection that I thought I was going to be ill. I could not comprehend it. It was as if a light in my heart and mind had suddenly been extinguished, leaving me in darkness. The "feeling" I had come to regard as an ever-present function, as much "mine" as my sense of sight or hearing, left me. From that moment I was unable to "feel" or sense anything. I could only reason things out. My intuition had died a sudden death. Why?

* * * * *

I cannot hope to describe the feeling of desolation that came over me. People came to me with their troubles, and I could only sympathize with them by common sense and reason. I walked the streets so people would not find me home. I went out alone at night under the stars to shed tears where none could see me, and to pray and sweat it out alone to find the answer. Why? Why?

The election came and went. McKinley won by a little over 800,000 majority. I bought a copy of the paper with the headlines I had "seen" in answer to my mental query that had somehow betrayed me. Then I found that Mr. J.W.A., as a member of the Board of Trade, had cashed in on my prediction to an extent that netted him a profit of one hundred and fifty thousand dollars or more.

What was the answer? As days went into weeks, weeks into months, I was to ask myself that question a thousand time, until I had written the answer so deeply that it was never to be forgotten.

There was only one answer, and I couldn't squirm out of it, no matter how I tried to reason it out. My eyes and ears were mine to use or misuse at will. But the "feeling" was a gift that I was not free to misuse without suffering the penalty of losing it. Perhaps there was some natural law I did not understand, and which I had unknowingly violated. Perhaps it was an operation of a "spirit of truth" or intelligence, such as the Bible described.

In any case, whatever I had believed as a child, whatever I might now assume from a rational standpoint, coincident with "coming of age" as an adult citizen of these United States, I was painfully faced with the fact that my nervous system had sustained a relationship with some unknown "source" of inspirational energy that operated only on conditions; that I was still largely ignorant of those conditions; that as a child I had not been expected to know those conditions; but that now as an adult I was responsible for the violation of those conditions, even through the instrumentality of others. Ignorance of the law appeared to be no excuse.

The whole affair appeared to originate in my conversation with J.W.A. Whatever the fault, I was to blame, not he. I did not receive one penny from him as a result of his profits from my prediction, yet I was paying the price for it. And he never knew nor could he have understood the price I paid.

Other men had profited in one way or another from the by-products of my mental experiments, but not to this extent. Then why, in principle, make an issue of this case? Was it because I had given away without discrimination what had been given me in private as an answer to my own question, asked for a very different reason?

* * * * *

In any case, here I was with only logic and reason left to me, forced to conclusions against which my logic and reason revolted. What I had regarded as a physiological operation of my nervous system, which involved "feelings" as tangible as those of heat and cold and electrical currents, had proved to depend only in a secondary sense on the physiological and nervous mechanism I possessed. Primarily it depended upon the operation or co-operation of something "other than myself," and I was undergoing a reluctant proof of this fact by having the primary "current" shut off. My prayers and tears and torture were of no avail. I had to think my own thoughts; the thrill of having them induced by inspiration was mine no more.

It was then that I knew what made charlatans and fraudulent spiritists, even granting that they had possessed some kind of gift. For if and when they lost it for any reason at all, they were obliged to go on by "pretending." Because they commercialized it, their livelihood depended on it; and when it failed them they substituted tricks.

It became evident to me that there was some kind of spiritual ethics that was not very well understood. So I made up my mind that I would prepare myself with a better foundation for making use of intuition, if I should ever succeed in regaining what I had lost. And this included insuring my own future freedom and independence, with a means of livelihood that would not be incompatible with a continuation of my research, though not dependent on it from a psychological angle.

To this end I went to work at any job I could find; spent all the money I could spare on instruments and apparatus, and all my spare time familiarizing myself by experiment rather than textbooks with the principles of electricity, chemistry, and microscopy. I bought the finest microscope that I could obtain at that time; and because it was a better one than any of my doctor friends possessed, I worked with them evenings in return for specimen. Thus I started my studies of biology and physiology, having made up my mind that if the gates of my mind were going to stay closed, I would take up medicine and become a doctor.

But I did not fix my mind too strongly on this thought, because I still had the vision of workshops and a research laboratory, where, if my intuition did not fail me altogether, I would delve into the mysteries of nature that constituted the still unsolved problems of science and support this dream of pure research by an occasional invention of a practical kind.

Thus ended the first twenty-three years of my life, with the loss of the "feeling" that had led me through all, from childhood.

Exactly one year to the day from the time my "feeling" left me, it returned again; just as if an electrical switch, long disconnected, was again turned on.

What this exactitude of period might mean I did not then know. It was as if I had been sentenced to one year in "jail," a jail with only two windows, my eyes; and all the other gates of my mind barred shut. For though I could hear, what I heard meant little. And though I could still smell the odor of flowers in spring, the experience stirred no response. The flavor of food gave me no pleasure; my appetite was gone. Things that I touched were cold or warm, rough or smooth, but I could not feel them a part of me, to interpret their hidden meanings as I had done since childhood. My imagination and emotions, which had previously been ever active, sensitive to respond, were during this year entirely dormant.

For the first time I felt the deficiency of my education; for now what had been the source of my understanding was no longer active. I felt that I knew nothing whatever about anything at all. So I set out to learn what I could while working for a living along with thousands of others who were serving "sentences" longer and harder than mine, in the endless treadmill of the civilization of a large city.

The story of that year would be superfluous to this record. Suffice to say that in that time I was reduced to the humility of realizing that "in myself I am nothing," and that other men in themselves were nothing; that without inspiration all men were nothing but electrochemical, biophysical mechanisms.

Then what was inspiration: What was the "current," and from whence, that brought life to dormant nerves, vision and understanding to the mind? I could see that men did not realize. The blind followed the blind, and none of them knew.

What made men great musicians, great artists, poets, surgeons, scientists, leaders, prophets? Was it the men themselves? What and whence the energy, the enthusiasm, the ambition, the hope, and faith the vision that took the clay of the earth, the body of an animal, and raised up out of the mob a great and lonely man?

And why did men flourish for a season, rise up inspired and speak their piece to thrill a nation, only to sink back to the level of a beast again, with a glaze over their eyes, a palsied hand, a pathetic ghost of a once-great man?

Only now did I know the answer, in the only way that one can ever know the answer to anything, by a personal experience. My little light hadn't lit up a very large area; it was the light of a boy, not a leader. I was not a great musician, artist, or anything else. Comparatively few people even knew I existed. But my light had gone out. And I could see in the lives of other men that they too had flashed a greater light than mine but it had gone out.

We were the wires and the bulb, the machine and the motor; but without the "current" we were nothing but that. It required a man plus "something else." Without the man, the "something else" could not manifest. Without the man the "something else" would be without hands, without voice, without strings to play a melody. But conversely, without that "something else" men are but the clay of the earth, and go the way of all flesh as a herd of educated human animals. And I could see that if man did not sustain a proper relation with that "something else," it left him as quickly as the snapping off of a switch or the burning out of a light.

* * * * *

Further I could see that it was this "something else" that had been responsible for all scientific progress; and still the scientists could only dissect the mechanism, trace the circuits of the nerves, and experiment with the functions and disorders of the organs; but science had not yet detected the function in its own progress of that "something else" that caused even the hearts of scientists to burn with the thrill of great discoveries, which they ignorantly presumed themselves to be making because they rightly assumed that their thoughts and conclusions consisted of happy correlations of their own observations, experiments, and sensory experience; but they wrongly ignored the function of the very energy that animated them in the fusion of their memories as an activity of understanding, failing to realize that without this inspiration they could not have been led to make the discovery: that it was not "accidental," as they thought; and that were it not for the "something else," they would have gone the way of all the uninspired on the endless treadmill of the world's repetition of routine.

And still further I could see that religion had developed a vocabulary with which to do a lot of talking and preaching about this "something else," which had shown what it could do with men now dead for centuries, but seemed careful not to imply too strongly or to encourage the expectations that even granting the omnipotence of that "something else" it can do the same things today.

If the sun had gone out, whence the heat and life of earth and man at this moment? But with my own light out, I could understand the past tense of religions from which the light had fled: living on memories, doctrines and speculative beliefs. What else was left? What indeed could we do but cling as best we might to a lost faith that, having ceased to be operative physiologically, had become a legend, where people worshiped at an empty grave that was but a reflection of their own lives, from which the living, vibrant "something else" had fled, leaving but an echo and a "word"?

So I who had stayed outside of the churches that could not feed me with a living God, to fill every nerve with life and understanding; I who had said, "Fill me with the spirit if there is such a thing; don't talk to me about it" - now I could understand. My heart ached for us all. I, too, now lived on a memory that began to fade like an echo without a voice to sustain it.

* * * * *

I say all this in the hope of conveying some understanding of what it meant to be released again from the prison of my own skull; the gates of my mind flung open once more, dormant nerves alive again, so that the whole universe from which I had seemed to be a separate thing now seemed to be inside, instead of outside my head. The moon, the sun, and the stars, the trees and the people, I saw in that moment seemed to be as much a part of me as my own hands and feet.

I shook hands with a friend, and suddenly felt a pain in the lower right side of my abdomen. Not having seen him for some time I asked him how he was, and he told me he had ruptured himself lifting a heavy packing case.

I was introduced to a man and a woman, total strangers to me. When I looked at the head of the man I imagined for an instant that it resembled a long, high bridge. When I looked at the woman, for a moment her face seemed to me to be that of an old man holding a violin under his chin. When I laughingly told them about it, the man said, "That is strange I am working on the specifications for a new ridge over the Mississippi River. I am an engineer."

The woman said, "Why, whatever made you say that? I never heard of such a thing! I have been thinking of just such a man. I met him at a musical in Paris, and he promised to give me lessons when I returned. I am planning to go there now."

A man was brought to see me by a friend who said, "Joseph, this man has heard of your mental experiments and would like to talk with you about them."

When I shook hands with him, a feeling of cold crept up my arm like a cold draft that went all through me and chilled me from head to foot. I was hard put to it to complete the handshake courteously, without betraying my revulsion to the feeling.

During the meaningless formalities of opening a conversation, I kept asking myself, "Now what does that mean? What does that feeling mean?" But my mind went blank, and produced no answer. That was the answer, and I didn't know it at first.

The man said, "I thought perhaps you could tell me something of what I ought to do. I have become confused in my mind, and the doctors can't help me with it. They don't find anything wrong with me physically."

I said, "Well, I can tell you what you are going to have to do, if you don't let up a little, and take better care of yourself. You are going to have to take a long rest."

"Do you think I should quit working for a while?"

"Try it for a week," I said, "And then let's talk about it again. Take a week off at once, and just rest. Then come to see me."

But I never saw him again. My friend told me that he dropped dead at his work, having arranged to finish the week out before taking a vacation.

Thus began a long period of adjustment between myself as a physiological mechanism, of which I now had a better knowledge, and the rest of the universe in connection with which there was "something else" that appeared to be establishing a relation with my imagination and memory through the involuntary nervous system.

It was not all clear sailing, and I proceeded with a caution I had not exerted before, as I was determined both to test out its limitations, or perhaps I had better say my limitations, and still avoid losing it again.

There appeared to be a "code" or language of "feeling" combined with mental imagery by which I could learn to extend the range of my interpretation of conditions. For example, the cold draft up the arm, and the inability to imagine anything when death was near, and there was nothing that could be said or done.

Then, too, there were lessons to be learned regarding the conditions necessary to sustain a cooperative relation between the voluntary and the involuntary nervous systems. Perhaps it was well not to spend time theorizing about it, but rather merely to state a few of the facts.

Some of my friends thought I had suddenly developed a "conscience," but I had given that considerable thought, and I knew it was not what they meant by the word. Conscience to most of them was merely a matter of childhood training as to what was right or wrong; and later in life, a social conscience based on public opinion and fear of criticism, "what people would think," and so on.

On the other hand, there is a private conscience of moral arbitration that governs conduct even in solitude on the basis of self-respect, ideals, and aspirations. With this type of conscience I was acquainted from childhood. No, what I was now experiencing was a period of systematic training (call it self-training, if you wish), in which my voluntary nervous system was obliged to place itself in submission to the involuntary nervous system for self-preservative reasons.

The bargain that intuition seems to drive is that it will serve you if you serve it. You must obey your intuition to cultivate it, to develop it, and to retain the use of it. This is a voluntary act. In colloquial language, you have a hunch, and the hunch is an involuntary experience. Whether or not you obey it is up to you. If it is a real hunch, or intuition, you will inevitably regret it if you do not. These experiences will increase in frequency if you obey them; and if you don't they will cease altogether. This is evident from case histories.

But to complete the transaction one must go further than that. One must recondition the entire system of reflexes that constitute habit, so that neither habit nor sensory stimuli nor the influence or suggestions of environments, thoughts, desires, or purposes of other people can interfere with the function or execution of your intuition of your relation between your inner self and that universal "something else." That must come before all else - "or else," in the final transaction.

If this had not been the case to some extent with myself previously, I would have hit the drift with my hammer at the time when it would have exploded the dynamite cartridge I didn't know was there. In that and many other cases where I was not alert to exercise any caution of intuition, I would not be here to write this record if my involuntary nervous system had not been responsive to "something else" besides my own will, knowledge, experience, or senses. My arm refused to obey. On other occasions it had done just the reverse, by making a sudden movement, to my own astonishment, to prevent an accident that I had failed to prevent by a voluntary intuitive alertness.

* * * * *

So now this proclivity appeared to be undergoing a period of calisthenics in a series of minor issues. I would start to smoke, and experience a feeling not to do so. If I heeded it, well and good. If not, my hand would drop or throw the match away before I could light up. I have never felt required to stop smoking, but I was definitely stopped from inhaling the smoke, limited in amount, and prevented upon occasion.

I have never been a drinker, and all my life have believed and practiced moderation in all things. Therefore an occasional drink was always in order. But now I had the occasional experience (apparently as a sort of involuntary "exercise") of having a glass in my hand but being unable to drink it.

One day I was asked to join a group on an excursion into the country, and the prospect pleased me. A day in the country away from the city was something that I would enjoy. I had "Yes, I would be glad to go" already framed and on the way to my vocal cords, but it came out, "No, I'm sorry. I can't go."

"Why not?"

That stumped me. There was no logical reason. I wanted to go. I couldn't answer and did not feel like making false excuses to the one who was urging me, so I merely smiled and shook my head. This met with an argument. Why did I "spoil the party," and so on. They thought me stubborn. I said I would be glad to go, that I really wanted to go, but not just then. If they would wait until the day after tomorrow, I would go; but not the next day.

So the whole trip was postponed in order to have me go with them. Next day the train we would have taken was derailed in a gulley; three were killed and many injured.

This was my wages, and countless other occasions like it, for "playing the game" that developed and conditioned involuntary reflex actions to the promptings of an intuitive feeling. If I had not allowed myself to respond to the reactions that threw a match away before I could light a smoke, and stopped my hand before it could raise a drink to my mouth, I would have been without that hand and perhaps my eyes from an explosion, and I would have said what I tried to say, "Yes, I would be glad to go," and we would all have been on the train that was wrecked.

And still, it is interesting to note that in "playing the game" above mentioned, I have in the long run never been disproved of anything, but have been merely reduced to moderation in all things. First, however, I had to demonstrate a willingness to give up anything and everything, to do things I did not want to do, and to refrain from things I did want to do - all to the end of clearing the road for the greater freedom.

Friends have thought that I was obeying an "impulse." No, it is not that. It is an intuitive determination to follow an inspired thought. The thought is my own, an activity of my own mind and nervous system, but an activity that would not take place unless it was induced by a feeling that constitutes inspiration, and that emanates from "something else," not my own.

I have utterly failed from the viewpoint of science and psychology to be able to account for the results of experiments in field or laboratory without that "something else." I find by investigation that men who can do so on a purely mechanistic basis are themselves merely talking machines confined to the electrical recordings of their verbal memory. My radio is mechanistic also, but it has to have a "broadcasting station"; and that is the "something else."

I confess there are no "call letters" to the human radio "station." I do not know what or who or where the "vibrations" or radiant energy comes from that is transformed into an activity of the imagination by means of selective stimulation of memory elements, but I do know that, so far as I am concerned, together with my associates through many years of research, on the basis of experience, observation, and experiment, on an operational, not a theoretical scientific, basis, we have established the fact for ourselves that man's survival and progress on a level superior to that of an intelligent animal depends entirely upon his rising above the level of a talking machine and establishing a relation as a "receiver" to "something else."

Name it what you please, it will still be the source of all inspiration, all great art, music, literature, culture, and scientific discoveries. And it will still be what has produced the world's scriptures and spiritual concepts. All the evidence we can deduce today tends to establish the fact that one Jesus of Nazareth and His apostles knew what they were talking about; and that the mental activity of those who think otherwise is confined to the reflective operations of the sensory and verbal memory. This is indeed a self-sufficient "mechanism," and that only, but without any dependable relation with truth or the rest of the universe, unless it is responsive to the "something else" that has the power to shape out of the sensory and verbal memory an activity of the imagination that corresponds with or portrays not only past and present, near and distant, but also future facts.

This is something that each individual may test out for himself. It is possible for any and every human being to "prophesy," if he will fulfill the conditions. The survival of our Christian civilization depends on it. It cannot survive on the basis of doctrinal beliefs or a legendary, speculative faith. It must be an operative faith, rooted in a physiological inspiration of prophetic intuition that will restore to mankind his heritage of spiritual gifts.

This is the inner nature of the present historic crisis, and I foresaw this crisis and described it more than fifty years ago. The survival of our Christian-American civilization and democratic way of life depends on it. Christianity will survive, but not the speculative churches, and not our democratic way of life unless history is supplemented by prophecy; and unless a doctrinal God is supplanted by a living God and a phenomenal "something else" that can enter our lives through our nervous system on a basis at least equal to that of the radio broadcasting that now perpetually enters our ears.

I have for half a century since the early period that serves the purpose of this commentary lived my life to discover, to prove, and to exemplify this truth, and the conditions that make such a relation possible. But that is still another story. And it includes the finding of Mary Lillian, the building of my home and laboratories in the Valley of the Pines, the birth of my sons, and the records of my search and research for the truths we understand and live by.

(FIRST EDITION ENDED HERE)