SelfDefinition.Org

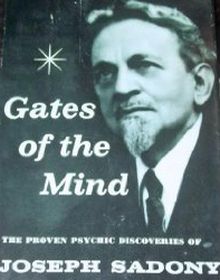

Gates of the Mind

The Proven Psychic Discoveries of

Joseph Sadony

Chapter 1

My mother was showing me a picture. She said, "That is where I was born, Joseph."

For a minute I looked at it, and it didn't seem right. I said, "But, Mother, shouldn't there be a river over here?" I pointed to the right. "And shouldn't there be a barn besides just a house?"

"What makes you say that, Joey? The artist made this just like it was. No, we were away from the river. We had no barn. What makes you say that?"

"Well, anyway," I said, "I remember the river, and a barn and a bridge."

Mother said, "Joseph, you mustn't talk like that. You never went as far as the river. You couldn't possibly remember it. Besides, that's where your father was born. It was his father who had a - " Suddenly my mother stopped and looked at me biting her lower lip. For a moment she seemed not to see me, though looking right at me.

I said, "Mother! What's the matter?"

She said, "Joseph, you couldn't possibly remember that, because you were never there, but that's where your father was born, by the river, near a bridge. And your grandfather had a barn, because he had horses. That was on the Rhine, near Coblens."

* * * * *

Herman was my only brother, and he was older than I was. When I was seven he was twelve. He was a cripple from birth, but he was beautiful and he was good. I always went to Herman when I didn't understand something and no one else would talk with me.

It was spring, and we were watching a robin build a nest outside the window.

I said, "Do you think that's the same one that built there last year, the nest that fell down when the wind blew this winter?"

Herman said, "I think it's maybe one of the young ones that was born in the old nest."

I said, "But how would it know? If it was born in the old nest, how would it know how to build a new one? Can a mother robin teach it?"

"But how?" I insisted.

"Well, they call it instinct, Joey, but what that is I can't tell you. I guess it's born in them because the mother and father knew; back and back so far that nobody knows anything about it."

"Herman, do you think we know things because Mother and Father knew them, even if they don't tell us?"

"Well, I think maybe we feel things and do things like they did, Joey. I've heard Father say you are sometimes just like Grandpa Jean Marie Felix Reipert. He was a bookbinder, like Uncle, and an artist too, always working with his hands, making things like you do."

I said, "Herman, sometimes I feel as if I could almost remember things before I was born. But just when I think I do, I forget it again. Do you ever feel that way?"

Herman said, "Well, I know what you mean. It's like a dream. When you wake up you can't remember it, but you know you were dreaming.

I said, "Yes, only it's not when I'm asleep, Herman. It's when I'm awake, and when I've been thinking and then stop thinking for a minute. When I start thinking again, it's gone."

Herman looked at me a minute and said, "You've always been funny that way, Joey. When you say things without thinking you are usually right, and everyone wonders how you know. But when you think about things you act as if you didn't know anything at all. I suppose you know that sometimes worries Mother, because she's afraid Father won't understand it. He doesn't like that sort of thing one little bit."

"But what can I do about it, Herman?"

"Well, I wouldn't say too much without thinking when Father is around. It's better when he thinks you're dumb than when he worries, wondering what's got into you. Some day I'll tell you why he worries about it."

"Tell me, Herman! Please tell me!"

"Ssh! Joey, they'll hear us. I'll tell you sometime when nobody's home but you and me."

It was pitch dark and I woke from a nightmare in a cold sweat. I must have cried out in my sleep because Mother had her hand over my mouth, whispering, "Be quiet, Joseph! Don't wake your father. What were you dreaming?"

I said, "I dreamed that Herman was hanging on the wall with his arms out, like on a cross. He was nailed there."

My mother gasped and said, "Joey! Promise me you won't tell anyone that! Don't tell your father, and don't tell Herman or your sisters."

I promised, and then asked, "Why?"

"Because," she said, "your father doesn't like such things, and we mustn't think of the or tell about them. But you frighten me."

"I'm sorry, Mother."

"I'm not blaming you, Joseph. You can't help how strange it is. I dreamed a dream like that about Herman the night you were born, and I didn't dare say anything about it. Because eight months before you were born I started dreaming strange dreams, and they all came true. That never happened to me before, and it has never happened since you were born. But during that time all my dreams came true except that last one about Herman. You're the first I've told, because now you dream it too! Let us say a prayer, Joey, and not tell anyone."

So Mother left me, but I didn't sleep. Something troubled me, but I did not know what it was. It was something more than my dream about Herman; something that made me feel all alone in the world, even with a large family.

I lay in the dark; then suddenly something happened to me that I did not comprehend until years later, in memory. The vague distress of an internal conflict I could not understand suddenly vanished. In that moment I gained a new sense of identity. Yet I felt like a stranger in the bosom of my own family. Suddenly I didn't know who I was, and lay there in the dark asking myself, "Who am I? Where am I? How did I get here?"

But there was no uneasiness in the sensation; rather a sense of impending excitement, as if I had entered a new world and could hardly wait to explore it. Somewhere in this new world a treasure was hidden, and I would find it. For some reason my heart was glowing as if I had fallen in love with something I couldn't see. All my inner senses were affected by this, so that strong, tender arms picked me up, but I could see no face because I was suddenly tired, and suddenly safe. When I woke it was morning.

* * * * *

The world was the same, after all; but something inside of me was different. I felt happy about something and didn't know why, I saw more than I usually did. I stopped to look at things that I usually passed by; and when I looked at the same old things I had seen every day, I now saw something I hadn't before, and identified them in my mind. I heard sounds and knew what they meant without turning my head to look. I felt the urge to go out exploring, but suddenly felt the need of sharing all this new world with someone who would understand it. I thought of Herman, but he was crippled and couldn't go with me.

So I stayed home with Herman, I couldn't tell him about my dream, so I asked him, "Herman, can't you tell me now why Father worries about what gets into me? Mother is outside now. No one will hear us. The girls have gone too. What is Father worried about? What does he think is going to happen to me?"

"Well, he thinks something gets into you, Joey. And he doesn't know whether it's a devil or an angel. Sometimes he's sure it's a devil, and that it'll lead you to no good end. Remember how one time you would run off with his gun and go shooting by the castle on the Rhine ; and next thing he knew you would be playing priest with an old soap box for an altar, serving mass? One day you would be catching crabs down by the pond, and spend hours looking at the worms you would break out of those long stick-like things you found. And next day you would imitate Saint Joseph, and say you wanted to be a carpenter."

"Do I have to be the same all the time, Herman?"

"Not for my part, Joey. That's what I like about you. One never knows what you are going to say or do next."

"Doesn't Father like that?"

"Well, it isn't just that. It's when you say things about the future, or when you seem so positive about something you couldn't possibly know. And when things happen to you that are mysterious."

"But nothing mysterious happens to me, Herman."

"Do you remember the time you had Uncle take you coasting on Montabaur hill? You didn't have a sled, so you took a ladder instead. The hill was all ice, and at the bottom was the crossroad. Uncle said a team of horses was coming, but it was too late for him to stop you, and you could not stop yourself. He said there was nothing on earth could keep you from being killed or badly hurt."

"But I wasn't hurt a bit, Herman."

"That's just the thing, Joey. Ladder and all, you shot right through between the legs of the horses, entirely unhurt. How did you do it? You didn't know. No one knew. That was a mystery. And then when they asked you if you weren't frightened when you saw the team ahead of you, you said no, you weren't, because the minute you saw them you thought about something else and forgot all about them."

"Well, I did, Herman, I closed my eyes, and saw the picture in the church."

"Yes, I know, Joey. But you said you knew you weren't going to be hurt."

"I did know it. I wasn't hurt."

"Well, all right. I believe you. But I'm showing you what worries Father. When they asked you how you knew you weren't going to be hurt bad or killed, you said it was because you were going to marry a girl named Mary, with black eyes and dark hair when you were twenty-seven years old, so that's how you knew you weren't going to be killed before then."

"That's how I did know, Herman."

"Well, that's what Father doesn't like. It's either nonsense, or you know. And if you know, how do you know? He doesn't like it either way, Joey."

* * * * *

So that night I lay there again in the dark feeling like a stranger, I tried to remember how it all came about that I was there, and why I felt like I sometimes did. It was the "feeling" that made me say things and think things like Herman said Father didn't like, and Mother seemed to understand but hushed me up so he wouldn't hear me.

I was six years old we were still in Montabaur, when there began to be talk in the family about going to America. It was then that I began to be conscious of a world beyond the village limits, I climbed to the top of the hill to try to see some of it. I was alone, but I imagined that men were walking up the hill with me, and that I was one of them.

We all had on light, flexible suits of armor, like fish scales made of metal. There was a bright red cross on each breast, a sword in one hand and a Bible in the other.

It was fifty years before I found out, inadvertently, that the village of Montabaur and the hill I climbed that day were originally called Humbach; and that centuries before me the Crusaders had climbed that hill and looked down over the beautiful country, calling it "The Holy Land." The hill reminded them of that Mount that Christ had ascended to pray, with Peter, James and John, where He was transfigured before them. So they christened it Mount Tabor, and henceforth the little village at its foot was called Montabaur.

I did not know this as I trudged along that day, surrounded by the creation of my own imagination, a company of Christian warriors with swords and Bibles.

When I reached the top I still could not see America. So I closed my eyes, but all I could "see" was a lot of Indians. That was of course because of what I had heard about America.

* * * * *

So far as I know now I had no knowledge of the Crusaders, or in any case of their relation to the hill at Montabaur. Of course it is possible there was a foundation for the "image play" with my remembering it. The fact is here unimportant as the purpose of these early recollections is more to provide the background and to portray the general nature of early thought elements as based on experience.

At present this is merely illustrative of a later problem: What distinguishes a "true" imagination from a "false" one as an element of imaginative experience when it is regarded as an established fact that we can think only with what we have acquired to think with? In other words, all imaginative experience is made up of combinations and recombinations of elements of sensory experience with a physiological foundation. Nevertheless it has been established by experiment that the separate parts or memory elements may be put together correctly or incorrectly to form a true or false internal representation of external events or conditions. What distinguishes between the "true" and the "false" when immediate verification by observation or experiment is impossible?

The answer, later to be set forth more fully, is that the distinguishing characteristic of a "true" imagination is a "feeling" that must be felt in order to understand its nature.

I did not at first comprehend this, but now in looking back at many thousands of imaginative experiences of childhood and youth, I see that when the exercise of the imagination is either unaccompanied by any feeling whatsoever, or when the imagination produces a feeling as a result of its exercise (e.g. imagining Indians is followed by a feeling of excitement and anticipation), the imagination is not to be trusted unless a train of thought is followed back to determine its origin, and unless the logic and reason are sufficiently matured and trained to adjust and retouch the picture in accordance with experience, or reason based on observation and experiment.

On the other hand, if a certain type of "feeling" (which is a dominant experience throughout this record) precedes the exercise of the imagination, and in fact produces the imagination by selective stimulation and blending of memory elements to express, to clothe, to embody, or to interpret the "feeling," we have then a type of spiritual inspiration and mental phenomena that merits further investigation, to which an introduction will be found in these pages.

* * * * *

My first experiences of a distinction in feeling associated with imagination were largely unrealized at the time, but preserved in memory. In climbing Mount Tabor, for example, the "feeling" came over me first that I was not alone. This caused met to imagine myself surrounded with companions all starting out together for some distant place to fight a battle. We would have swords but we would also have Bibles. The Cross would be our armor inside, but outside we would need armor of steel.

I did not then realize that these details characterized the Crusaders, who gave the hill historic background and a name. All the elements were familiar to me, but not the history. My memory contained swords, Bibles, Crosses, metal armor, and the idea of men who would use these things. Emphatically, I did not see the "spirits" of Crusaders walking up the hill with me. What I "saw" was entirely the product of my own imagination in which was composited various elements of memory acquired by previous sensory experience.

But these memory elements were selectively stimulated, assembled, and imbued with life by a "feeling" at a particular time, under a particular condition, at a particular place, which invested them with a meaning I did not myself comprehend until fifty years later. Whence and what the "feeling"? Why the particular mental imagery evoked by the feeling? Not in these few childhood cases alone, but in thousands upon thousands of cases extending through a lifetime: my own and the lives of many others whose experiences I have investigated.

That was the quest in which, symbolically at least, I set forth with a sword in one hand and a Bible in the other, to find the answer. I sought the truth, and as time went on I found that my imagination provided the truth in one instance and deceived me in another. It deceived me when I used my own reason and memory to speculate on things I didn't know enough about. It deceived me when I concentrated or "tried." It never deceived me when I didn't try, and didn't care, and had a "feeling" first that started my imagination going to piece together in a flash what was aroused from my memory by the feeling. What was the feeling?

* * * * *

I stress this because as time went on people who knew more about such things than I would say, "The boy is psychic," or "He is clairvoyant." "It must be telepathy or psychometry," and so on.

And I knew they were all wrong. I possess no special, mystic, or occult sense that other men do not possess. My mental operations are limited entirely to what I have acquired and recorded by sensory experience. My imagination has only my own memory to draw on. I visualize something spontaneously past, present or future, near or far; it proves correct, with witnesses to verify it. My records contain thousands of such witnessed cases in which I was correct 98% of the time. What did I "see"? Nothing but a composite of my own memory elements of past experience.

Truly and literally it was "nothing but my imagination." Still it corresponded with the truth. Why? Was it a good guess? Was it "coincidence"? Was it "chance"? These were questions to be answered by experimental research. At first I did not know. But time ruled out chance beyond all dispute. And I did soon find out that man's most important thinking does not take place in the brain alone, but with the entire body and nervous system.

Truth is not to be found in man's memory of words or his reflective visual or oral thinking. Words and memories of sights and sounds may be woven together into endless combinations. What gives them meaning? What determines the exact word or memory elements that will be combined in any given concept or idea or train of thought? What assurances have we that our ideas have any correspondence with reality at all?

Our only assurance from a scientific point of view is one based on experience, observation and experiment. How then is it possible to know things in the future, at a distance in the present and in the past, without opportunity for experience, observation, or experiment? I can only say that I have established this fact for myself, that I am writing this commentary on my early experience to introduce you to what I did and how I did it, so you too may establish the facts for yourself, without taking anyone's word for it; mine or that of anyone else.

It requires not the use of some mysterious faculty you do not possess, but rather the suspension of the use of your "intellect"(verbal memory, reason, etc.) until after your feeling of intuition has clothed itself imaginatively. Then harness it by "logic and reason," by all means, if you can. But you must first learn how to stop thinking at will. You must learn how to "deconcentrate " instead of concentrating. You must make no strenuous "effort." You can't "force" it. You can't "play" with it. You can't "practice" it. Spontaneity is its most essential characteristic. It cannot manifest in the realm of habit or "conditioned reflexes," as in the case of instinct.

In the language of the New Testament, you must not try to move the spirit; you must let the spirit move you. This means that you must let the truth shape you, for the simple reason that you cannot shape the truth. Your relation to truth is direct, and not by reflective or verbal representation. You will find the truth neither in words nor in memories, but only in direct nervous coordination of the whole of your immediate sensory experience, internal as well as external.

Just as the law of crystallization and chemical combination in the mineral kingdom and the inorganic world, so also the law of selective absorption in the organic world and vegetable kingdom, preserving the species, materializing the truth and meaning of the seed. And so also the selective excitation and conditioning of reflexes in the formation and operation of instinct in the animal kingdom. And there is evidence that a similar law is at work in a more complicated system of self-conditioning reflexes as manifest in the Vastly superior nervous organization of man: a mechanism of adaptation not only to so-called seen or visible environments, but also to "unseen" environments such as those manifest in radiant energy and the specifications of future growth as manifest in seeds.

* * * * *

All I knew as a child was that I had some sort of relation with what I could neither see, hear, smell, taste nor touch; and that relation was a "feeling."

But I found that "thinking" and "imagining" first created a false feeling that lied to me. It was only when the feeling came first, without thinking, that the feeling was right. And my thoughts and imaginations were right only if they were induced by the feeling and not by association of thought resulting from what I saw or heard. Sometimes there was nothing in my experience to fit the feelings that came to me. Often I could not understand them at all in terms of word or ideas familiar to me. Still I "knew"; but I couldn't explain it.

I feel it necessary for the sake of the intellect of those who have had no such experiences to explain thus at length the view from which my own are regarded. None was regarded as occult or mystic in nature; none involved mysterious unknown senses, nor were they "extra-sensory" or "super-sensory." Man's relation with his environments, the universe, the rest of mankind, Deity, or forms of energy or life beyond his present understanding is regarded as a physiological, neurological, sensory relation. No responsive or imaginative activity is regarded as possible without a nervous organization with a physiological foundation. And I have established to my own satisfaction by experiment that if I apparently "see" a vision or dream, a dream that proves to be prophetic, there is no so-called faculty of prevision, or second sight. The "third eye" employed in such experiences is nothing more nor less than the "imagination" that every man, woman, and child exercises to a greater or lesser degree. This "mind's eye" of imagination has never, does not, cannot, and never will "see" anything outside of one's own physiological organization. Its sensations are entirely "memory sensations." It is strictly limited to the momentary and fragmentary revival of past experiences as recorded in memory. Its one and essential power, which distinguishes the complicated nervous organization of man from the more simple one of the animal, is the power of recombination by means of which the imagination can make new creations out of the memory elements of old experiences.

Thus we symbolize; we indulge in fantasy; we speculate and theorize; we create works of art; we invent; and thus we produce a culture and a civilization. But as we thus change environments, we change our "destiny," and we change the character of adaptation that operates in the law of the survival of the fit. It becomes necessary to adapt oneself to subtler and more complicated environments. It becomes necessary to develop foresight, a knowledge of consequences; to plan, to prepare, to prevent. We find that only those who do this survive.

So now we have a law of the survival of the intuitively fit. But intuition needs to be redefined, or we shall have to find a new word for it.

Possibly there was a time when brute strength survived, but it soon became evident that a less strong and more sensitive nervous organism better adapted itself to environments in the survival of the instinctively fit.

With the appearance of man there was a new element; intelligence. Neither brute strength nor instinct could cope with it. The intellect that could make a trap, dig a pitfall for mastodons, and invent a gun soon became king of the earth.

And then what, as men fight each other as well as the elements of nature, to say nothing of man's own creations, which break his bones and blast him from the face of the earth? Do the strong battle and kill themselves off so that the meek shall inherit the earth?

Man now finds others than himself to battle. He builds cities, and the earth trembles, opens great jaws and swallows them up. Volcanoes belch forth and bury them. Winds blow and lay them low. The rain falls and great floods sweep all before them. Lightning strikes and burns his structures to the ground. He builds ships and they sink at sea. He makes fast-moving engines and dashes to destruction. He digs in the bowels of the earth for its riches and is buried alive. The sun dries up his crops and he perishes in famine. Pestilence breaks out and leaves a city of dead to be buried unknown by the sands of ten thousand years, which he later digs up to decipher its records. And ever and anon, as the beating pulse of an eternal war drum, he goes to battle again, with ever increasing cunning in horrible devices with which to slay - himself.

It is the last cycle; the final "survival." And is it the strong who survive? Is it the cunning? Is it the meek? Is it the tyrant? Is it the selfish and arrogant? It is not. It is they who feel the "feeling" and act on it. It is they who had a "hunch" not to buy tickets on the ship that was going to sink. It is they who did not build a city where Vesuvius would belch forth its lava and flames. It is they who do not buy or build a house below the future flood-crest of a river. It is they who packed their belongings and left the day before an earthquake shattered their home. It is they who do these things without even thinking why.

What is the "feeling"? If we waited to use it until we knew what it was, we would be like the farmer who still uses kerosene lamps because he doesn't intend to use electricity until he knows what it is. The wren does not know why it flies south; but it flies, and thus escapes cold and starvation. An animal obeys a "feeling" directly, without translating it into words or thoughts of visual (imaginative) representation. Man has so far lost his neural relation with reality (by having substituted a world of words and symbolic representations) that he regards as abnormal those who retain it or regain it. He invests it with an air of mystery, and represents it by misleading words of special vocabularies, mystic, occult, theosophical, theological, psychological, and psychic.

* * * * *

The mystery is no longer in the physiological and nervous organization of man - not any more than in the construction of the Geiger counter. The mystery is in the so-called cosmic rays that act on the Geiger counter. What are they, and where are they from? The mystery is in the source of energy or life that acts on the nervous organization of man to produce the "feeling." What is it, and where is it from? There need be no other mystery. The organism upon which it acts is now fairly well known. New ductless glands will be discovered. Many functions and operations will be better understood. But in all its essentials the physiological foundation and nervous organization is well enough understood, in the light of developments in the field of electronics and radiant energy, to know that man is capable of experiencing "feelings" (independent of seeing, hearing, smelling, tasting, touching) that emanate from sources known or unknown. Heat is but an obvious example, as well as electrical conditions of the atmosphere.

Beyond this coordinated sensitivity of the entire nervous system no further or special sense is required. It is superfluous and absurd to postulate mysterious powers of vision, clairaudience, "psychic abilities," and so on, when the normal powers and modus operandi of imagination and memory not only suffice in explanation, but may be investigated experimentally to establish the fact that one's so-called psychic faculties are entirely limited constituently to the contents of the individual memory, just as the constituents of words are limited to the alphabet employed, and my verbal representation is limited to my vocabulary (i.e., my verbal memory), unless I pause to look up or coin a word for an idea that has not yet been incorporated in my verbal organization.

And yet I have had words come to mind and pass over my tongue in experimental conditions, words entirely unfamiliar to me, words in foreign languages, or technical terms that could be found in a dictionary, and some that could not, containing information that I did not myself knew, and that was verified as correct. I used familiar syllable, however. I used the familiar alphabet. And even where I inscribed hieroglyphics entirely unfamiliar to me, it was a composition of familiar smaller elements of lines and curves, shapes and angles. The fact still described in terms so vastly misleading and misunderstood as remains that my vision of these things cannot correctly be "psychic," telepathic, and so on. It was nothing whatever but imagination compositing familiar elements of previous sensory experience recorded in memory.

I see and correctly describe a scene ten thousand miles away. (I have done this under experimental conditions as recorded in my files.) I see and describe a future event, which occurs exactly as I described it, with only minor variations. What is lacking or faulty in my description is lacking in my memory. For what so I see? Nothing but my own imagination.

Actually I do not see ten thousand miles away with any form of "vision" whatever. I do not "see" the future. My reception or perception of these things is entirely formless, entirely a "feeling," entirely devoid of image, word, thought or concept. What makes it intelligible to myself or someone else is the activity of my imagination, which endeavors to symbolize, portray or interpret the "feeling."

And what is the "feeling"? That is the one great mystery. That is the quest. That is the source of all inspiration, the fountainhead of all spiritual gifts, the heart and life of all religion. This is the foundation that science has provided for spiritual understanding: a physiological foundation for a nervous organization that responds to an unknown source or sources of energy in the form of "feelings." These feelings are neurological and physiological; not the activity of a special or occult "sense," but the coordinated activity of the entire nervous organization. The reaction is one of selective stimulation of previously experienced and conditioned reflex arcs of memory. The imagination interprets the "feeling" in terms of memories associated with similar feelings. Thus a complex feeling is broken down into its elements by symbolic representation in an imaginative composite of memory elements. Thereby we "understand" it.

* * * * *

With this explanation we may hope to contribute to a better understanding of mental phenomena stripped of the deceiving terminology of generations of "psychic racketeering." Man's "all-seeing eye" is his imagination, and his imagination sees not beyond his own nerve ends. It sees only the "past" that has been recorded in memory. Still, by this means he may portray what has not yet been recorded (i.e., the future); he may "see" around the world; and he may explore the past before his birth in the history of the human race. And why? Because his quivering nerves are open to the universe and susceptible to innumerable feelings. The feelings stimulate and thus clothe themselves in reawakened memory sensations.

Thus we do not see the past, present or future beyond the range of our senses, but we "imagine" it. And if our "feeling" is genuine, our imagination is "true."

Can there be a "false feeling"? Yes, when it is merely the echo of a past feeling aroused by suggestion, association of thought, and memory of words: i.e., intellectual activity in general. The "feeling from outside" can bring you information of a phenomenal nature only when you are able to suspend all internal activity of thought. The "feeling" must have an empty slate to write on. It must be allowed to select your memories, to shape them in your imagination, to choose its own words. The result will be instantaneous; and until you understand the language of feeling, you may not be able to distinguish such formations from your own thoughts. Or, on the other hand, the experience may be so pronounced that you will think you see a "vision," a "spirit" or a "ghost."

You may feel indignant if others call it a hallucination or "imagination," but that is exactly what it is, nothing more. Still, it may be a genuine experience and the "vision" may be true in every detail within the capacity of your memory to provide the necessary elements.

To help you understand how this can be, and to help you to distinguish between false and true, the wrong and right use of the imagination, the false echo from the genuine feeling, I have taken these pains both to record and to comment on my own personal adventures and research along these lines.

* * * * *

Not everything is easy to explain, but we must avoid attaching the "mystery" to the wrong place. Within all seeds is the "design" of what they will become by growth and development. The creative power exists in the unrecorded. What has been recorded is already "dead." Thus the creative and progressive power in man necessarily manifests as a prophetic power, active in determining what he shall be, and not what he has been.

What has been inherited or already determined as a conditioned reflex is of the past. But what selects or chooses, as in the power of selective absorption of a seed, or the power of selective stimulation in physiological man, is of the "future" in function of "time," which exists solely as a biological phenomenon of succession in growth.

Thus there are innumerable sources of prophetic "feeling" in man that need not be the occasion of any "mystery." In our very careless and inadequate verbal organization we speak of wishes, wants, desires, appetites, hunger; of ambition, aspiration, ideals; hope, anticipation, expectations, faith, and so on. These terms are neither clearly understood, defined nor differentiated; and means have not been provided to distinguish between those sources of prophetic feeling that are inherent to the structure of our physiological organization, as in the case of animals whose cycle of progressive activity repeats itself each generation, and those sources of prophetic feeling that are not inherent to the individual physiological structure but which manifest in human progress, which repeats itself in cycles extending through several generations.

To the latter we must attach the "mystery." Self-preservation is not a remarkable phenomenon, but race-preservation is. The man who will fight to preserve himself or his family is not a particularly interesting object of study, but the man who will live his life and give his life for the sake of mankind and human progress is manifesting the mystery that is the religion of mankind. What is the source of his "feelings"?

* * * * *

But to return to my own experiences, I have found that whereas "memory is not inherited (i.e., it is not possible to "remember" before we were born in terms of our ability to recall our own sensory experience since birth), we do nevertheless inherit enough of our parents, and through them of past ancestors, to manifest a "feeling" that is capable of arousing parallel memories in our own experience. And thus our imagination may approximate some condition or memory of a parent or ancestor before our birth.

I make this statement on the basis of considerable evidence. Often, however, there is a composite of elements derived from both father and mother, so that the feeling is complex and the resulting imagination a mixture.

Just what caused my mother to dream prophetic dreams while bearing me, and not any of the other children, is something that I do not even attempt to explain. What caused me to dream at the age of seven, going on eight, on a night when I was "reborn" by a distinct psychological change, a dream similar to one my mother dreamed the night I was born one month too soon - that again is something I cannot explain at this stage of the record. And why we both should have dreamed that Herman was hanging on the wall, nailed there as if he had been crucified, might possibly be considered a coincidence, in view of the fact that the symbolism is not unusual in a Catholic family; and if we consider crucifixion to be a symbol of suffering, it could certainly apply to poor Herman, a cripple from birth.

Nevertheless I can swear that under the circumstances neither Mother nor I breathed a word to Herman about that dream; nor did we tell anyone else, on account of Father's attitude toward such things.

We could not regard the dream as prophetic in a literal sense, since it would be absurd to think that Herman would ever really be found hanging on the wall. At most we could regard it as symbolic, and at worst as symbolic of death. But the dream of a series that had not come true, and it had upset her so much at the time that I was precipitated into the world in a premature birth.

Therefore our feelings can be imagined when Herman called Mother one day, after a spell of suffering, and said, "Mother, hang me on the wall here!"

Shocked, and thinking he was perhaps delirious, she asked, "And why should I do that?"

He answered, "Because I want to die like Christ died."

Mother said, "But you are not going to die, Herman! Don't talk that way."

He answered, "Yes, I am, Mother."

She put her arm about him, and they prayed together. Then Herman cried himself to sleep.

He never woke up again.