SelfDefinition.Org

The Role of Celibacy in the Spiritual Life

El rol del celibato en la vida espiritual

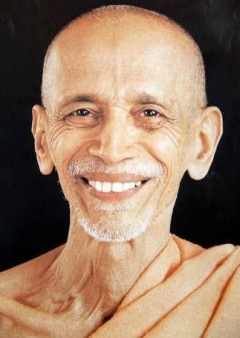

Swami Chidananda Saraswati

Swami Chidananda Saraswati

Introduction, by Swami Chidananda

Esta página en español: introduccion.htm

Publisher’s Note

In October, 1997, His Holiness Sri Swami Chidananda—who in 1963 succeeded His Holiness Sri Swami Sivananda Maharaj as president of the Divine Life Society—was interviewed by a leading American spiritual magazine, ["What is Enlightenment?"] on the question of the role of celibacy in the spiritual life.

This very powerful booklet is a presentation of the questions asked and the answers given. It provides the sincere spiritual seeker with rare insights, not only into the role of celibacy in the spiritual life, but into the goal of life itself, enlightenment.

The publishers are happy to release this valuable booklet on July 3, 1998, the auspicious 50th anniversary of the Yoga Vedanta Forest Academy, which is an important and integral part of the Divine Life Society headquarters, Sivananda Ashram, Rishikesh, India.

– THE DIVINE LIFE SOCIETY

Source: www.dlshq.org

Introduction, by Swami Chidananda

In considering the role of celibacy in the spiritual life, it is important to remember that, in the context of Hindu society, the subject of brahmacharya or celibacy or self-restraint does not necessarily have any connection at all with the spiritual life, or sadhana (spiritual practices), or with Self-realisation as such. It is not normally discussed or recommended only with a view to promote spiritual life. The situation is totally different because of a certain uniqueness that has come to be part and parcel of the life of a Hindu in Indian-Hindu society.

That uniqueness is that our ancients have drawn up a certain social structure and also a pattern of social life for the individual. In ancient India, a person’s life was reckoned as 100 years, divided into four stages. The first stage was the student stage, or brahmacharya stage, where the young people were expected to study hard, build a good physique, cultivate a noble character and in all ways prepare themselves for their adult lives. During this first stage they were expected to observe strict celibacy.

The second stage was the householder stage, where the exercise of the sexual faculty was taken for granted and recognised as a legitimate part of human life. It was regarded as a fundamental, sacred duty of a family to create and offer progeny to form the next generation—for the perpetuation of society and also of the species. So here there was no question of celibacy in the strict sense of the term implying total abstinence. On the other hand, the exercise of sex was an indispensable duty for the householder. Of course, its exercise was not meant to be unbridled and unrestrained; otherwise it would be degrading. But it was given the full sanction of society and was considered to he something sacred and quite accepted.

The third stage of life was the retired stage, when the couple turned over to their sons the burdens of earning a living and themselves turned their minds to higher things. Here again brahmacharya was expected. The lawgivers said: "Do you want to go on being just a physical creature, bound down to physical consciousness, all your life? Now, raise your consciousness above its present total identification with the body and aspire to go higher!" So they said, restraint is necessary. But peculiarly enough this restraint was not an ordinary restraint; it was a sort of a challenge. It became part of their sadhana.

Then during the fourth stage, one’s entire life was to be devoted to God and God alone. One became a sannyasin, or monk, and then, of course, celibacy was automatically total. Therefore, the concept of brahmacharva was part and parcel of the Indian-Hindu social tradition. In its narrowest, restricted sense, brahmacharya meant complete celibacy, but in its broader sense, as it could be applied to the life of a householder, it meant moderation and self-restraint, not abusing the sex function, and strict fidelity to one’s partner.

Man is a mixture of three ingredients: first, an animal with all the physical propensities and sense urges that one shares in common with animals; second, the rational, logical human level; and third, the dormant Divinity, the sleeping God within. The whole of the spiritual life is a gradual elimination, eradication, of the animal within, and the refinement or purification and education of the entire human nature so that it stops its movement in all other directions and starts taking on an ascending vertical direction. Once the human nature is given an upward turn, one simultaneously starts awakening the sleeping Divinity with the help of all one’s spiritual practices.

If one knows that the spiritual process, the spiritual life, is the elimination of the animal, the refining and directing upwards of the human, and the awakening and unfoldment of the Divine, then all spiritual practices, including the role that brahmacharya plays, fall into their right place.

– Swami Chidananda