SelfDefinition.Org

The Zen Master in America

Dressing the Donkey with Bells and Scarves

by Stuart Lachs

4. Suzuki Roshi Meets Soen Nakagawa Roshi

Text

"In other words, always remain conscious of what you are doing, of what is going on." [70]

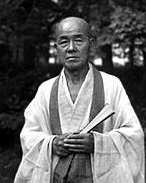

Soen Nakagawa

(1907-1984)

In the autumn of 1971 Suzuki roshi was ill and left Tassajara for what was understood to be his last visit. On the drive back to San Francisco, he and his party stopped at a retreat center near San Juan Bautista where Soen Nakagawa roshi [Wikipedia] was in the last hours of a weeklong sesshin (meditation retreat). Soen Nakagawa roshi was a prominent Rinzai roshi known in the West for his iconoclasm, theatrical displays, poetry and his connections to a number of teachers who brought Zen to the U.S.A. [71]

Though Suzuki did not feel well the next day, he gave the Saturday lecture at the City Center during which time he described the visit with Soen roshi.

"At the end of his sesshin we bowed more than thirty times, calling out many buddhas' names. He called some special names: Sunshine Buddha, Moonlight Buddha, Dead Sea Buddha, and Good Practice Buddha. Many buddhas appeared and bowed and bowed and bowed. That is something beyond our understanding. When he bowed to all those buddhas, the buddhas he bowed to were beyond his own understanding. Again and again he did it.

"And he served us matcha [powdered green tea] from a bowl which he made himself. What was he doing, I don't know, and he didn't know. He looked very happy, but that happiness is very different from the happiness we usual people have. Our practice should go to that level, where there is no human problem, no Buddha problem, where there is nothing. To have tea, to have cake, to make a trip from one place to another is his practice. He has no idea of helping people. What he is doing is helping, but he himself has no idea of helping people." [72]

What happened to the heretofore simple and down-to-earth Suzuki roshi? It is one thing to admire a peer, a fellow roshi. It is another to raise the description to an ecstatic level. Was Suzuki, weak and ill, confusing performance with attainment, flamboyance with wisdom? Was he equating a different set of religious rituals with the perfected attainment of a Zen master?

Suzuki rhapsodizes over Soen's ability to connect with the "other" world, to call upon many Buddhas by name, so that they "appeared and bowed and bowed and bowed." Suzuki declares that Soen, whom he clearly idealizes, not only expresses his attainment and compassion perfectly and effortlessly in the simple tasks of daily life, but also is a conjurer of the "other" world. As portrayed by even the down-to-earth Suzuki roshi, Soen is master over all worlds and situations while remaining perfectly pure, at ease, desireless, and empty. Soen is presented as a sacred being, a living Buddha.

Zen teaches that one must be an enlightened being to recognize another enlightened being. In presenting Soen as a living Buddha to his trusting flock, Suzuki is implicitly claiming the same status for himself. In an act of Zen self-verification, both Suzuki and Soen are seen as living Buddhas. In doing so, Suzuki has brought the original perfection of the Buddha in to the present, as described earlier by Bourdieu's model.

In this portrayal of original perfection, both Suzuki and Soen, in their roles as roshi, appear as the "locale" of the sacred imbued with mysterious power. [73] They "consecrate themselves, monopolize the notions of Truth, Wisdom, and Freedom and thereby draw a boundary between themselves and ordinary people." [74]

We have one, supposedly enlightened Zen master, Suzuki roshi, acting as the grand narrator, describing in idealized terms [75] another, supposedly enlightened Zen master as being above the rest of the world, with happiness different from everyone else's happiness, which is beyond everyone else's ("usual people") understanding. Suzuki describes Soen's practice as just "to have tea, to have cake, to make a trip from one place to another." What he is doing is helping, but "he has no idea of helping people." Suzuki claims to understand these actions, which are beyond the understanding of "usual people." Is not Suzuki too, a "usual person" in his "utter ordinariness"? [76] There are apparently not just different degrees of ordinariness, but different kinds. Suzuki claims Soen's behavior is beyond our understanding, implicitly stating that we are all the same in not understanding it. However, we should not be taken by rhetoric, since statements of sameness only have meaning when coming from some one with the authority to speak. Some one with little social capital saying that we are all the same has little or no weight. In the Zen context, a student speaking this way would be viewed as speaking out of place or above their position or understanding. Statements of sameness come from on high; "it is top dogs who get to legislate sameness, and, in fact, it is the very declaration of sameness that makes them superior." [77]

According to this "romantic" view put forth by Suzuki, Soen, besides giving a more than competent performance of a roshi, just does simple things: has tea and cake, is happy beyond our understanding, "no human problem, no Buddha problem," he goes from place to place and just his very being is helping people of which he is totally unaware. Soen is completely at ease and empty of any notions of self, of interests, of any idea or notions about his surroundings or other people. Suzuki describes Soen as returning to a wonderful simplicity, a perfectly empty being, flawlessly responding to the needs of his surroundings all the while being mystically in touch with countless Buddhas. [78] He is also, supposedly, happy beyond any ordinary human understanding. We must ask: Is such a thing possible? If so, is Soen such a person?

We see how Suzuki describes or shall we say sells or seduces his students with his flawless image of Soen. He does this without any reference to theory, history, or Zen principles, so that the complexity of a real person is replaced by a simple and iconic image. Suzuki is seducing his students with an image of Soen as the perfect Zen master, manifesting effortlessness, power, happiness, and the complete fulfillment of the path. [79] In fact, this false construction can be viewed as an underlying duplicity throughout Zen, which in this case is promulgated by Suzuki, albeit unconsciously.

Suzuki can speak rather off the cuff like this because he is describing a world-view that his own students, well socialized into American Zen culture, have fully internalized: the standard model of Zen. [80] They have experienced this repeatedly in Zen teachings, rituals, stories and talks. It is also so easily described and accepted because that is the space in which Zen exists: the ways of talking, ways of moving, ways of doing things, the views and understandings that makes the world have sense and value, in which it is worth investing one's time and energy. [81] Suzuki's words have particularly strong effects in this setting because he is preaching to the converted. It is just this frequency of repetition that enhances its reality-generating strength. Its strength is also enhanced in this case, because it is coming from the SFZC's supreme authority figure, Suzuki roshi. He is the group's legitimate spokesman. He is the group personified. [82] He is talking his students and perhaps himself, through an image of the idealized Zen roshi and making it "real" by giving it a body and name, a time and place in the real world. In effect Suzuki is saying, here is your perfected Zen man, Soen Nakagawa roshi, a living Buddha. I recognized him and hence myself as such, and bowed and had tea with him yesterday just a few miles down the coast.

Notes, part 4

[70] Crooked Cucumber, p. 312.

[71] Robert Aitken, Philip Kapleau, and Eido Shimano [see chapter 5] were former students of Soen Nakagawa. Yasutani roshi [see chapter 5, note 86] was a close friend of Soen's, who came to NYC in his place when his mother's illness kept him from visiting. More will be said about Soen in the next section of the paper.

[72] Crooked Cucumber, pp. 386-387.

[73] The Sacred Canopy, p.95. The mysterious power comes from internalizing the role legitimated by the religion. The socialized identity can then be apprehended by the individual as something sacred.

[74] Language and Symbolic Power, p. 211. They make themselves synonyms of themselves, in effect saying, "I am the Truth."

[75] Language and Sympolic Power, see p. 203-219, "Delegation and Political Fetishism." Suzuki's words have power because he has the mandate of the group. However, in reality it is more or less true to say that it is the spokesperson/

[76] Zen Mind, Beginner's Mind, p. 18. Baker's description of Suzuki and all roshi ("A roshi is") ends with, "it is not the extraordinariness of the teacher that perplexes, intrigues, and deepens the student, it is the teacher's utter ordinariness."

[77] Cole, Alan, Text as Father, University of California Press, 2005, p.201.

[78] Berger, The Sacred Canopy, pp.35, 36. Berger discusses the unique capacity of religion to "locate" human phenomena within a cosmic frame of reference.

[79] The description of effortlessness and simplicity would resonate well with Suzuki's students as it contrasted so with their Zen practice. Besides starting the day at 4 A.M. with meditation, many had families and jobs to balance, they also attended week long sitting meditation retreats (J. sesshin) and when possible three month long training periods (J. ango) at the Center's monastery, Tassaraja. For many, the long meditation periods could be painful. Their lives would hardly be described as effortless and simple.

[80] See last paragraph p.3.

[81] Jenkins, Pierre Bourdieu, p. 75. According to Bourdieu, daily life can be elucidated without falling into the pitfalls of mechanistic explanations. Deliberate intentions do not account for everything people do. See also Bourdieu and Wacquaint, An Invitation to Reflexive Sociology, pp. 126, 127.

[82] Bourdieu, Pierre, In Other Words: Essays Towards a Reflexive Sociology, Stanford University Press, 1990, p. 139. The chapter "Social Space and Symbolic Power," pp. 123-139 is relevant to the discussion of roshi/Zen masters and their students.