SelfDefinition.Org

The Psychology of Man's Possible Evolution

P.D. Ouspensky

Fourth Lecture

Esta página en espanol: conferencia-4.htm

The Centres

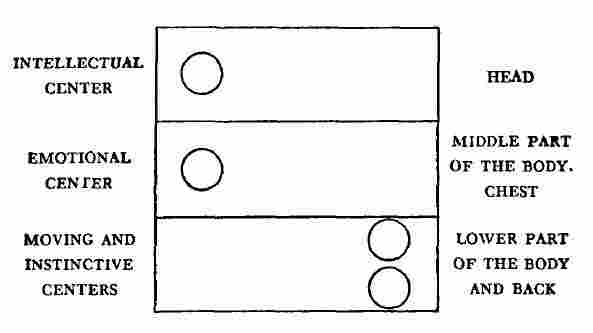

We shall begin today with a more detailed examination of centres. This is the diagram of four centres.

| Intellectual centre | Head |

| Emotional centre | Middle part of the body. Chest |

|

Moving centre

Instinctive centre |

Lower part of the body and back |

<--- front of body back --->

Image credit: Vintage edition (1973) fair use

The diagram represents a man standing sideways, looking to the left, and indicates the relative position of centres in a very schematic way.

In reality each centre occupies the whole body, penetrates, so to speak, the whole organism. At the same time, each centre has what is called its 'centre of gravity.' The centre of gravity of the intellectual centre is in the brain; the centre of gravity of the emotional centre is in the solar plexus; the centres of gravity of the moving and instinctive centres are in the spinal cord.

It must be understood that in the present state of scientific knowledge we have no means of verifying this statement, chiefly because each centre includes in itself many properties which are still unknown to ordinary science and even to anatomy. It may sound strange, but the fact is that the anatomy of the human body is far from being a completed science.

So the study of centres, which are hidden from us, must begin with the observation of their functions, which are quite open for our investigation.

This is quite a usual course. In the different sciences—physics, chemistry, astronomy, physiology—when we cannot reach the facts or objects or matters we wish to study, we have to begin with an investigation of their results or traces. In this case we shall be dealing with the direct functions of centres; so all that we establish about functions can be applied to centres.

All centres have much in common and, at the same time, each centre has its own peculiar characteristics which must always be kept in mind. [1]

[1. Also see Maurice Nicoll's diagrams: /gurdjieff/

Speed or Time of Centres

One of the most important principles that must be understood in relation to centres is the great difference in their speed, that is, a difference in the speeds of their functions.

The slowest is the intellectual centre. Next to it—although very much faster—stand the moving and instinctive centres, which have more or less the same speed. The fastest of all is the emotional centre, though in the state of 'waking sleep' it works only very rarely with anything approximating to its real speed, and generally works with the speed of the instinctive and moving centres.

Observations can help us to establish a great difference in the speeds of functions, but they cannot give us the exact figures. In reality the difference is very great, greater than one can imagine as being possible between functions of the same organism. As I have just said, with our ordinary means we cannot calculate the difference in the speed of centres, but, if we are told what it is, we can find many facts which will confirm not the figures but the existence of the enormous difference.

So before bringing in figures, I want to speak about ordinary observations which can be made without any special knowledge.

Try, for instance, to compare the speed of mental processes with moving functions. Try to observe yourself when you have to perform many quick simultaneous movements, as when driving a car in a very crowded street, or riding fast on a bad road, or doing any work requiring quick judgment and quick movements. You will see at once that you cannot observe all your movements. You will either have to slow them down or miss the greater part of your observations; otherwise you will risk an accident and probably have one if you persist in observing.

There are many similar observations which can be made, particularly on the emotional centre which is still faster. Everyone of us really has many observations on the different speeds of our functions, but only very rarely do we know the value of our observations and experiences. Only when we know the principle do we begin to understand our own previous observations.

At the same time it must be said that all the figures referring to these different speeds are established and known in school systems. As you will see later, the difference in the speed of centres is a very strange figure which has a cosmic meaning, that is, it enters into many cosmic processes or, it is better to say it divides many cosmic processes one from another. This figure is 30,000. This means that the moving and instinctive centres are 30,000 times faster than the intellectual centre. And the emotional centre, when it works with its proper speed, is 30,000 times faster than the moving and instinctive centres. [2]

[2. Modern analogies could be processor speed or bandwidth. But "cosmic meaning" seems to imply different hydrogens.]

It is difficult to believe in such an enormous difference in the speeds of functions in the same organism. It actually means that different centres have a quite different time. The instinctive and moving centres have 30,000 times longer time than the intellectual centre, and the emotional centre has 30,000 times longer time than the moving and instinctive centres.

Do you understand clearly what 'longer time' means? It means that, for every kind of work that a centre has to do, it has so much more time. However strange it may be, this fact of the great difference in the speed of centres explains many well-known phenomena which ordinary science cannot explain and which it generally passes over in silence, or simply refuses to discuss. I am referring now to the astonishing and quite inexplicable speed of some of the physiological and mental processes.

For instance—a man drinks a glass of brandy, and immediately in no more than a second, he experiences many new feelings and sensations—a feeling of warmth, relaxation, relief, peace, contentment, well-being, or on the other hand, anger, irritation, and so on. What he feels may be different in different cases, but the fact remains that the body responds to the stimulant very quickly, almost at once.

There is really no need to speak about brandy or any other stimulant; if a man is very thirsty or very hungry, a glass of water or a piece of bread will produce the same quick effect.

Similar phenomena representing the enormous speed of certain processes can be noticed, for instance, in observing dreams. I referred to some of these observations in A New Model of the Universe.

The difference is again either between the instinctive and the intellectual centres or between the moving and the intellectual. But we are so accustomed to these phenomena that we rarely think how strange and incomprehensible they are.

Of course, for a man who has never thought about himself and never tried to study himself, there is nothing strange in this or in anything else. But in reality, from the point of view of ordinary physiology, these phenomena look almost miraculous.

A physiologist knows how many complicated processes must be gone through between swallowing brandy or a glass of water and feeling its effects. Every substance entering the body by way of the mouth has to be analysed, tried in several different ways and only then accepted or rejected. And all this happens in one second or less. It is a miracle, and at the same time it is not.

For, if we know the difference in the speed of centres and remember that the instinctive centre, which has to do this work, has 30,000 times more time than the intellectual centre by which we measure our ordinary time, we can understand how it may happen. It means that the instinctive centre has not one second, but about eight hours of its own time for this work, and in eight hours this work can certainly be done in an ordinary laboratory without any unnecessary haste. So our idea of the extraordinary speed of this work is purely an illusion which we have because we think that our ordinary time, or the time of the intellectual centre, is the only time which exists.

We shall return later on to the study of the difference in speed of centres.

Positive and Negative Parts

Now we must try to understand another characteristic of centres which will later give us very good material for self-observation and for work upon ourselves.

It is supposed that each centre is divided into two parts, positive and negative. [3] This division is particularly clear in the intellectual centre and in the instinctive centre.

[3. Also see Maurice Nicoll's diagrams: /gurdjieff/

Yes and No

All the work of the intellectual centre is divided into two parts: affirmation and negation; yes and no. In every moment of our thinking, either one outweighs the other, or they come to a moment of equal strength in indecision. The negative part of the intellectual centre is as useful as the positive part, and any diminishing of the strength of the one in relation to the other results in mental disorders.

In the work of the instinctive centre the division is also quite clear, and both parts, positive and negative, or pleasant and unpleasant, are equally necessary for a right orientation in life.

Pleasant sensations of taste, smell, touch, temperature, warmth, coolness, fresh air—all indicate conditions which are beneficial for life; and unpleasant sensations of bad taste, bad smell, unpleasant touch, feeling of oppressive heat or extreme cold, all indicate conditions which can be harmful to life.

It may definitely be said that no true orientation in life is possible without both pleasant and unpleasant sensations. They are the real guidance of all animal life on the earth and any defect in them results in a lack of orientation and a consequent danger of illness and death. Think how quickly a man would poison himself if he lost all sense of taste and smell, or if, in some unnatural way, he conquered in himself a natural disgust of unpleasant sensations.

In the moving centre the division into two parts, positive and negative, has only a logical meaning: that is, movement as opposed to rest. It has no meaning for practical observation.

Emotional Centre

In the emotional centre, at a first glance, the division is quite simple and obvious. If we take pleasant emotions such as joy, sympathy, affection, self-confidence, as belonging to the positive part, and unpleasant emotions such as boredom, irritation, jealousy, envy, fear, as belonging to the negative part, things will look very simple; but in reality they are much more complicated.

To begin with, in the emotional centre there is no natural negative part. The greater part of negative emotions are artificial; they do not belong to the emotional centre proper and are based on instinctive emotions which are quite unrelated to them but which are transformed by imagination and identification. This is the real meaning of the theory of James and Lange, at one time very well-known. They insisted that all emotions were really sensations of changes in inner organs and tissues, changes which took place before sensations, and were the actual cause of sensations. [4]

[4. Physiological arousal instigates the experience of emotion. en.wikipedia.org/

That really meant that external events and inner realisations did not produce emotions. External events and inner realisations produced inner reflexes which produced sensations; and these were interpreted as emotions.

No positive emotions in ordinary state

At the same time positive emotions such as 'love,' hope,' 'faith' in the sense in which they are usually understood—that is, as permanent emotions—are impossible for a man in the ordinary state of consciousness. They require higher states of consciousness; they require inner unity, self-consciousness, permanent 'I' and will.

Positive emotions are emotions which cannot become negative. But all our pleasant emotions such as joy, sympathy, affection, self-confidence, can, at any moment, turn into boredom, irritation envy, fear and so on. Love can turn into jealousy or fear to lose what one loves, or into anger and hatred; hope can turn into daydreaming and the expectation of impossible things, and faith can turn into superstition and a weak acceptance of comforting nonsense.

Even a purely intellectual emotion—the desire for knowledge, or an aesthetic emotion; that is, a feeling of beauty or harmony—if it becomes mixed with identification, immediately unites with emotions of a negative kind such as self-pride, vanity, selfishness, conceit and so on.

So we can say without any possibility of mistake that we can have no positive emotions. At the same time, in actual fact, we have no negative emotions which exist without imagination and identification.

Of course it cannot be denied that besides the many and varied kinds of physical suffering which belong to the instinctive centre, man has many kinds of mental suffering which belong to the emotional centre. He has many sorrows, griefs, fears, apprehensions and so on which cannot be avoided and are as closely connected with man's life as illness, pain and death. But these mental sufferings are very different from negative emotions which are based on imagination and identification.

Negative Emotions

These emotions are a terrible phenomenon. They occupy an enormous place in our life. Of many people it is possible to say that all their lives are regulated and controlled, and in the end ruined, by negative emotions, At the same time negative emotions do not play any useful part at all in our lives. They do not help our orientation, they do not give us any knowledge, they do not guide us in any sensible manner. On the contrary, they spoil all our pleasures, they make life a burden to us and they very effectively prevent our possible development because there is nothing more mechanical in our life than negative emotions.

Negative emotions can never come under our control. People who think they can control their negative emotions and manifest them when they want to, simply deceive themselves. Negative emotions depend on identification; if identification is destroyed in some particular case, they disappear.

The strangest and most fantastic fact about negative emotions is that people actually worship them. I think that, for an ordinary mechanical man, the most difficult thing to realise is that his own and other people's negative emotions, have no value whatever and do not contain anything noble, anything beautiful or anything strong.

In reality, negative emotions contain nothing but weakness, and very often the beginning of hysteria, insanity or crime. The only good thing about them is that, being quite useless and artificially created by imagination and identification, they can be destroyed without any loss. And this is the only chance of escape that man has.

Inner development, sacrifice

If negative emotions were useful or necessary for any, even the smallest purpose, and if they were a function of a really existing part of the emotional centre, man would have no chance; because no inner development is possible so long as man keeps his negative emotions.

In school language it is said on the subject of the struggle with negative emotions:

Man must sacrifice his suffering.

'What could be easier to sacrifice?' everyone will say. But in reality people would sacrifice anything rather than their negative emotions. There is no pleasure and no enjoyment man would not sacrifice for quite small reasons, but he will never sacrifice his suffering. And in a sense there is a reason for this.

In a quite superstitious way man expects to gain something by sacrificing his pleasures, but he cannot expect anything for sacrifice of his suffering. He is full of wrong ideas about suffering—he still thinks that suffering is sent to him by God or by gods for his punishment or for his edification, and he will even be afraid to hear of the possibility of getting rid of his suffering in such a simple way.

The idea is made even more difficult by the existence of many sufferings from which man really cannot get rid, and of many other sufferings which are entirely based on man's imagination, which he cannot and will not give up, like the idea of injustice, for instance, and the belief in the possibility of destroying injustice.

Besides that, many people have nothing but negative emotions. All their I's are negative. If you were to take negative emotions away from them, they would simply collapse and go up in smoke.

And what would happen to all our life, without negative emotions? What would happen to what we call art, to the theatre, to drama, to most novels?

Unfortunately there is no chance of negative emotions disappearing. Negative emotions can be conquered and can disappear only with the help of school knowledge and school methods. The struggle against negative emotions is a part of school training and is closely connected with all school work.

What is the origin of negative emotions if they are artificial, unnatural and useless? As we do not know the origin of man we cannot discuss this question, and we can speak about negative emotions and their origin only in relation to ourselves and our lives. For instance, in watching children we can see how they are taught negative emotions and how they learn them themselves through imitation of grown-ups and older children.

If, from the earliest days of his life, a child could be put among people who have no negative emotions, he would probably have none, or so very few that they could be easily conquered by right education. But in actual life things happen quite differently, and with the help of all the examples he can see and hear, with the help of reading, the cinema and so on, a child of about ten already knows the whole scale of negative emotions and can imagine them, reproduce them, and identify with them as well as any grown-up man.

True picture of our emotional life

In grown-up people negative emotions are supported by the constant justification and glorification of them in literature and art, and by personal self-justification and self-indulgence. Even when we become tired of them we do not believe that we can become quite free from them.

In reality, we have much more power over negative emotions than we think, particularly when we already know how dangerous they are and how urgent is the struggle with them. But we find too many excuses for them, and swim in the seas of self-pity and selfishness, as the case may be, finding fault in everything except ourselves.

All that has just been said shows that we are in a very strange position in relation to our emotional centre. It has no positive part, and no negative part. Most of its negative functions are invented and there are many people who have never in their lives experienced any real emotion, so completely is their time occupied with imaginary emotions.

So we cannot say that our emotional centre is divided into two parts, positive and negative. We can only say that we have pleasant emotions and unpleasant emotions, and that all of them which are not negative at a given moment can turn into negative emotions under the slightest provocations or even without any provocation.

This is the true picture of our emotional life, and if we look sincerely at ourselves we must realise that so long as we cultivate and admire in ourselves all these poisonous emotions we cannot expect to be able to develop unity, consciousness or will. If such development were possible, then all these negative emotions would enter into our new being and become permanent in us. This would mean that it would be impossible for us ever to get rid of them. Luckily for us, such a thing cannot happen.

Nothing permanent

In our present state the only good thing about us is that there is nothing permanent in us. If anything becomes permanent in our present state, it means insanity. Only lunatics can have a permanent ego.

Incidentally this fact disposes of another false term that crept into the psychological language of the day from the so-called psycho-analysis: I mean the word 'complex.'

There is nothing in our psychological make-up that corresponds to the idea of 'complex.' In the psychiatry of the nineteenth century, what is now called 'complex' was called a 'fixed idea,' and 'fixed ideas' were taken as signs of insanity. And that remains perfectly correct.

Normal man cannot have 'fixed ideas' 'complexes' or 'fixations'. It is useful to remember this in case someone tries to find complexes in you. We have many bad features as it is and our chances are very small even without complexes.

Work on Ourselves

Returning now to the question of work on ourselves we must ask ourselves what our chances actually are. We must discover in ourselves functions and manifestations which we can, to a certain extent, control, and we must exercise control, trying to increase it as much as possible.

For instance, we have a certain control over our movements, and in many schools, particularly in the East, work on oneself begins with acquiring as full a control over movements as possible. But this needs special training, very much time and the study of very elaborate exercises. Under the conditions of modern life we have more control over our thoughts, and in connection with this there is a special method by which we may work on the development of our consciousness using that instrument which is most obedient to our will; that is, our mind, or the intellectual centre.

In order to understand more clearly what I am going to say, you must try to remember that we have no control over our consciousness. When I said that we can become more conscious, or that a man can be made conscious for a moment simply by asking him if he is conscious or not, I used the words 'conscious' or 'consciousness' in a relative sense. There are so many degrees of consciousness and every higher degree means 'consciousness' in relation to a lower degree.

But, if we have no control over consciousness itself, we have a certain control over our thinking about consciousness, and we can construct our thinking in such a way as to bring consciousness. What I mean is that by giving to our thoughts the direction which they would have in a moment of consciousness, we can, in this way, induce consciousness.

Self-observation

Now try to formulate what you noticed when you tried to observe yourself.

You noticed three things:

- First, that you do not remember yourself; that is, that you are not aware of yourself at the time when you try to observe yourself.

- Second, that observation is made difficult by the incessant stream of thoughts, images, echoes of conversation, fragments of emotions, flowing through your mind and very often distracting your attention from observation.

- And third, that the moment you start self-observation something in you starts imagination; and self-observation, if you really try it, is a constant struggle with imagination.

Self-Remembering

Now this is the chief point in work upon oneself. If one realises that all the difficulties in the work depend on the fact that one cannot remember oneself, one already knows what one must do.

One must try to remember oneself.

In order to do this one must struggle with mechanical thoughts and one must struggle with imagination.

If one does this conscientiously and persistently one will see results in a comparatively short time. But one must not think that it is easy or that one can master this practice immediately.

Self-remembering, as it is called, is a very difficult thing to learn to practice. It must not be based on an expectation of results, otherwise one can identify with one's efforts. It must be based on the realisation of the fact that we do not remember ourselvesl; and that at the same time we can remember ourselves if we try sufficiently hard and in the right way.

We cannot become conscious at will, at the moment when we want to, because we have no command over states of consciousness. But we can remember ourselves for a short time, at will, because we have a certain command over our thoughts. And if we start remembering ourselves, by the special construction of our thoughts—that is, by the realisation that we do not remember ourselves, that nobody remembers himself, and by realising all that this means—this will bring us to consciousness.

You must remember that we have found the weak spot in the walls of our mechanicalness. This is the knowledge that we do not remember ourselves, and the realisation that we can try to remember ourselves. Up to this moment our task has only been self-study. Now, with the understanding of the necessity for actual change in ourselves, work begins.

Later on you will learn that the practice of self-remembering, connected with self-observation and with the struggle against imagination, has not only a psychological meaning, but it also changes the subtlest part of our metabolism and produces definite chemical, or perhaps it is better to say alchemical, effects in our body. So today from psychology we have come to alchemy; that is, to the idea of the transformation of coarse elements into finer ones.