SelfDefinition.Org

The Supreme Doctrine

Hubert Benoit

Zen and the Psychology of Transformation

Chapter 10 Metaphysical Distress

When I am distressed in connexion with any circumstance of my life, what is happening in me? My distress is the result of meeting the Not-Self, it expresses my fear of being defeated in this encounter. Since I unceasingly try the action between my being and my nullity in connexion with the particular circumstances of my life, my distress expresses my fear of being condemned in this action. I have tried to conquer the Not-Self, and here I am, afraid that I may not succeed, and of being brought face to face, in this failure, with the negation of my being.

But I would not have tried to conquer the Not-Self and to win the case of my being if this case had not first of all existed in the depths of me, if a doubt had not dwelt in me regarding my being. As a result, behind the distress that I have felt in the momentary failure of my case, there is another distress, a permanent distress which supports my case itself. Behind the phenomenal, or physical distress, felt on the plane of phenomena, there is a noumenal, or metaphysical distress, which dwells up-stream of my phenomena.

This metaphysical distress is the original, or primary distress which conditions my ordinary, secondary distress. We will try to specify its nature.

First of all it is unconscious. The man who has not attained Realisation is conscious of phenomena only; he could not, therefore, be conscious of a distress which is up-stream of phenomena. Besides let us see what happens in us when we are joyous; I am joyous because I feel myself to be affirmed in the antagonism Self-Not-Self, because my inner lawsuit is momentarily going well, in process of being won. But, behind this joy which depends upon the turn for the better of my lawsuit, this lawsuit still goes on, and so a doubt concerning my being, and so metaphysical distress; metaphysical distress lies at the origin of my joys as well as of my conscious distress; and it is the unconscious element therein.

Unconscious metaphysical distress, then, is also characterised by permanence. It is always there, always the same, behind all our affective phenomena and their dualism Joy-Suffering.

We will demonstrate besides that it is illusory, unreal, that it 'is' not (although it has seemed to us to 'be' just now, noumenally), but simply that all our affective phenomena occur as though it existed.

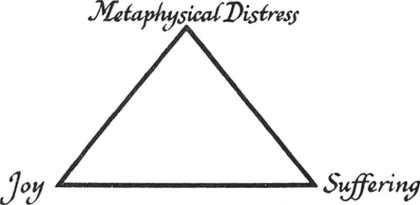

Let us note that it constitutes, with the joy and the suffering that it conditions, the triangle that we know already, whose apex represents the conciliatory principle and whose inferior angles represent the inferior positive and negative principles:

But this triangle may surprise us; as opposed to what we have seen in all the other cases the superior principle here carries a negative appellation. Why? This corresponds with the fact that Faith is asleep in the man who has not attained realisation, with the fact that this man whose Faith is asleep does not see his Buddha-nature. Because this man does not see his Buddha-nature everything happens in him as though this nature, which however is his, were lacking in him. Because the Being is not awakened in the man's centre everything happens in him as though, in this centre, there reigned a Nullity which it then becomes necessary to refute. Because the perfect existential Felicity is not awakened in the centre of this man everything happens as if this centre were occupied by a primordial distress. But this primordial distress 'is' not.

We understand thus that our recent triangle was badly drawn; it would be more accurate to draw it thus:

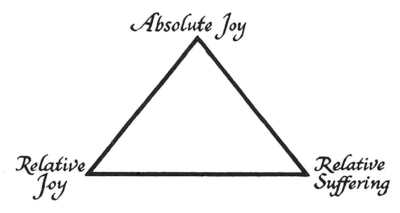

It is a triangle illusorily inversed by ignorance. In the case of the man enlightened by satori this inversion disappears and the triangle becomes:

Metaphysical distress cannot be conscious since it is entirely illusory. Man cannot become conscious of it without it annihilating itself. One cannot even say that satori results from the fact of becoming conscious of metaphysical distress; it is better to say that satori occurs when the man's centre awakens, this centre in which the metaphysical distress is supposed to reside as long as the centre is asleep.

All the forms of distress that man can feel consciously are secondary distress; none deserves the name of primary or metaphysical distress. Sometimes man is distressed concerning the great philosophical problems that touch on his condition, that is to say he is distressed concerning metaphysical questions; but this man is tormented by mental images, by phenomena, by forms; he suffers on the phenomenal plane—physical not metaphysical. Another man can be distressed at the thought of renouncing certain illusory compensations; he can then believe that this distress at the idea of losing his personality and merging in the universal deserves the name of metaphysical distress. But this man has a false conception of renunciation; he does not know that true renunciation is a passing beyond that which has been depreciated by the understanding interpreting experience; this man is not, as he believes, distressed by the universal but by the particular values to which he is still attached and which are menaced by a false conception of Realisation. No distress that is consciously felt could be called metaphysical; there could not be distress at the level of the Principle, at the level of our creative source.

On the other hand, we repeat there cannot exist any distress, consciously felt, which has not at its origin unconscious metaphysical distress, the reversed unconscious image of dormant existential Felicity. This fallacious unconscious image is the efficient cause of all our 'moral' suffering; the circumstances of our life, in connexion with which we suffer, are only, despite what we habitually believe, immediate causes. A mother who has lost her child does not suffer, as she believes, because her child is dead; she suffers, in connexion with this death, because she believes herself to have been abandoned by her Principle, she suffers because the occurrence has released in her the profound impression of not 'being'.

If no distress that is consciously felt can be the primary metaphysical distress it is important to see that our secondary distress is more or less removed from the fallacious primordial distress. Our distress is graded in a qualitative hierarchy according to the degree of depth of our understanding. My distress is at its furthest from my source if my understanding of the inner life is null, if I am fully persuaded that my concrete and particular grief is the real cause of my suffering. In proportion as I advance in the correct understanding of the inner life I escape from this trap; my belief in the causal role of the particular accidental circumstance decreases; I relate my suffering less and less to that which happens to me personally, and more and more to my universal human state, this state which I share with all human-beings. In the degree in which this understanding works effectively in me the lawsuit between my personal being and my personal nullity ceases to be pleaded; that is to say in the degree in which the causes of my distress become universal in my understanding I cease to suffer. The more my mental images lose their fascinating density, the more my distress becomes subtle and draws near its source, and the more this distress at the same time is attenuated. Thus one can perceive how understanding frees man little by little from his distress; the more profoundly I understand that my distress depends on a state that is in no way particular to me, the more there fades in me the famous and absurd lawsuit 'to be or not to be' from which comes all my misery. Understanding does not bring the lawsuit to a settlement, it scatters the phantoms of the illusory suit, and reduces progressively all the emotions which come from this 'cave of phantoms'. Thus we make our way towards satori. According to the descriptions of the Zen masters the inner states which precede and announce the release of satori are states of serenity, of affective neutrality. The consciousness of this man has gradually approached his centre, this centre at which it was supposed that metaphysical distress, mother of all distress, resides; the nearer he approaches it the lighter is his distress, so tenuous that it disappears altogether in the last moments which precede satori. The more he approaches the point at which metaphysical distress was supposed to reside, the more he recognises that he does not see it, the more he assures himself in this way that it has never been there. The painful belief disappears then in serenity; together with it there is abolished the spasm which was closing the 'third eye' and which forbade him until then the vision of perfect existential joy.