SelfDefinition.Org

The Supreme Doctrine

Hubert Benoit

Zen and the Psychology of Transformation

Chapter 2 'Good' and 'Evil'

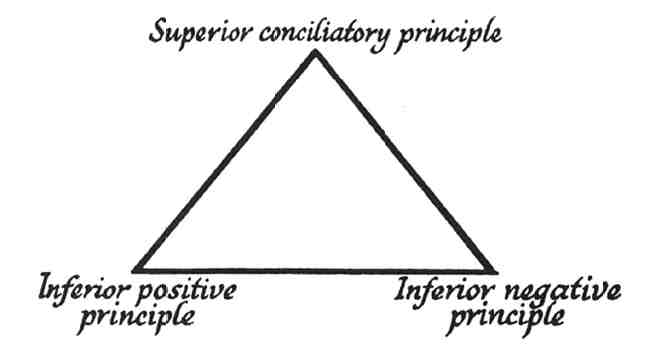

We know that Traditional Metaphysics represent the creation of the universe as the result of the interplay, concomitant and conciliatory, of two forces that oppose and complete one another. Creation results, then, from the interplay of three forces: a positive force, a negative force, and a conciliatory force. This 'Law of Three' can be symbolised by a triangle; the two lower angles of the triangle represent the two inferior principles of creation, positive and negative; the apex represents the Superior or Conciliatory Principle.

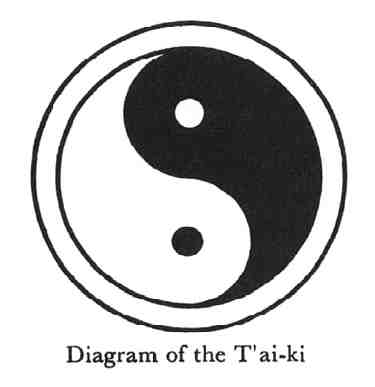

The two inferior principles are, according to Chinese wisdom, the two great cosmic forces of the Yang (positive, masculine, dry, hot) and of the Yin (negative, feminine, damp, cold) they are also the Red Dragon and the Green Dragon, whose unceasing struggle is the creative motive power of the 'Ten Thousand Things'.

The diagram of the T'ai-ki comprises a black part, the Yin, another which is white, the Yang, of strictly equal extent, and a circle that surrounds them both, which is the Tao (Superior Conciliatory Principle). The black part contains a white spot, and the white part a black spot, to show that no element of the created world is absolutely positive or absolutely negative. The primordial dualism Yang-Yin includes all the oppositions that we are able to imagine: summer-winter, day-night, movement-immobility, beauty-ugliness truth-error, construction-destruction, life-death, etc.

This last opposition is particularly stressed in one of the Hindu aspects of the Triad of which we treat: under the authority of Brahma, the Supreme Principle, creation is the simultaneous work of Vishnu, the 'Preserver of Beings', and of Siva, the 'Destroyer of Beings'.

The creation of the universe, such as we perceive it, unfolds in time; that is to say that the interplay of the two inferior principles is temporal. But these two principles themselves could not be considered as temporal, since they could not be subjected to the limitations which result from their interplay; they are intermediaries, placed between the Superior Principle and the created universe which is the manifestation of this Principle. Universal creation unfolds, then, in time, but is itself an intemporal process to which one can neither attribute nor deny beginning and end, since these words have no sense outside the limits of time. The most modern scientific theories here approach Metaphysics and attribute to the concrete universe neither beginning nor end.

It is very necessary to understand all this in order to free oneself completely from the infantile conception according to which a Creator, imagined anthropomorphically, has at one moment launched the universal movement. My body, for example, was not created only on the day on which I was conceived; it is being unceasingly created; at every moment of each year of my life my body is the seat of the birth and death of the cells which compose it, and it is this balanced struggle within me between the Yang and the Yin which goes on creating me up to the time of my death.

In this intemporal Triad which unceasingly creates our temporal world one sees the perfect equality of the two inferior principles. Their collaboration being necessary for the appearance of the mass of phenomena, in the appearance of any phenomenon, however small it may be, it is impossible to assign a superiority, either qualitative or quantitative, to either one or the other of these two principles. In one such phenomenon we can see the Yang predominating, in another such the Yin, but the two Dragons balance one another exactly in the spatial and temporal totality of the universe. Also the triangle which symbolises the creative Triad in Traditional Metaphysics has always been an isosceles triangle whose base is strictly horizontal.

The equality of the two inferior principles necessarily carries with it the equality of their manifestations regarded in the abstract. Siva being the equal of Vishnu, why should life be superior to death? What we are saying here is quite evident from the abstract point of view from which we are now looking. From this point of view why should we see the slightest superiority in construction over destruction, in affirmation over negation, in pleasure over suffering, in love over hate, etc.?

If we now leave aside pure intellectual thought, theoretical, abstract, and if we come down to our concrete psychology, we note two things; first of all our innate partiality for the positive manifestations, life, construction, goodness, beauty, truth; this is easily explained since this partiality is the translation by the intellect of an affective preference, and since this is the logical result of the will to live which is inherent in man. But we notice also something that is less readily explicable: when a metaphysician imagines a man who has attained 'realisation', freed from all irrational determinism, inwardly free and so living according to Reason, identified with the Supreme Principle and perfectly attached to the cosmic order, freed from an irrational need to live and from the preference that follows for life as against death, when a metaphysician imagines this man, he experiences an incontestible intuition that his actions are loving and constructive, and not based on hatred and destruction. We would not say that the man who has attained 'realisation' is loving and devoted to construction, for this man has gone beyond the dualistic sentiments of the ordinary man; but we are not able to see his actions otherwise than as loving and constructive. Why should the partiality that has disappeared from the mind of the man who has attained 'realisation' seem to have to persist in his demeanour? We must answer this question if we would completely understand the problem of 'Good' and 'Evil'.

Many philosophers have thought correctly enough in order to criticise our affective way of looking at Good and Evil and to deny it an absolute value—but often for the benefit of a system which, refuting this attitude in all that is erroneous, denies also all it has that is correct, and, taking man beyond a Good and an Evil that have been abolished, this system leaves him disorientated in the practical conduct of his life or hands him over to a morality that has been turned upside down. The difficulty is not in criticising our affective conception of Good and Evil, but in doing it in a way that will integrate it, without destroying it, in an understanding in which everything is conciliated.

Let us examine first of all, briefly, wherein lies the error that man habitually commits in face of this problem. Man perceives, outside himself and within, positive phenomena and negative phenomena, constructive and destructive. By virtue of his will to live he necessarily prefers construction to destruction. Being an animal endowed with an abstract intellect, generalising, he rises to the conception of construction in general and of destruction in general, that is to say to the conception of the two inferior principles, positive and negative. At this stage of thought the affective preference becomes an intellectual partiality, and the man thinks that the positive aspect of the world is 'good', that it is the only legitimate one, and that he ought to eliminate more and more completely the negative aspect which is 'evil'. Whence the nostalgia for a 'paradise' imagined as destitute of any negative aspect. At this imperfect stage of thought man comprehends the existence of the two inferior principles, but not that of the Superior Principle which conciliates them; also he perceives only the antagonistic character of the two Dragons, not their complementary aspect; he sees the two Dragons in combat, he does not see them collaborating in this struggle; also he necessarily experiences the absurd desire to see, at last, the 'Yes' triumph definitely over the 'No'. Distinguishing, for example, in himself the constructive impulses, which he calls 'qualities', and the destructive impulses, which he calls 'faults', he thinks that his true evolution should consist in eliminating entirely his 'faults', so that he may be animated only by the 'qualities'. Just as he has imagined 'paradise' so he imagines the 'saint', a man actuated by nothing but a perfect positivity, and he sets about copying this model. At best this mode of action will achieve a kind of training of the conditioned reflexes in which the negative impulses will be inhibited in the interests of the positive; but it is evident that such an evolution is incompatible with intemporal realisation, which presupposes the conciliatory synthesis of the positive and negative poles, and the fact that these two poles, without ceasing to oppose one another, can finally collaborate harmoniously.

The conception of the two inferior principles, when the idea of the Superior Principle is lacking, necessarily leads the man to bestow on these two inferior principles a nature at once absolute and personal, that is to say to idolise them. The positive principle becomes 'God' and the negative 'Devil'. When the apex of the triangle of the Triad is lacking the base of the triangle cannot remain horizontal; it swings a quarter of a turn: the inferior positive angle becomes 'God' and rises up to the zenith ('paradise'); the inferior negative angle becomes 'Devil' and falls to the nadir ('hell'). 'God' is conceived as a perfect anthropomorphic positivity, he is just, good, beautiful, affirming, constructive. 'Satan' is conceived as a perfect anthropomorphic negativity, he is unjust, wicked, ugly, negating, destructive. Since this dualism of the principles contradicts the intuition that man has, in other respects, of a Unique Principle which unifies everything, the existence of 'Evil', of 'Satan', opposed to 'God', poses to man a problem that is practically insoluble and forces him into philosophical acrobatics. Among these acrobatics, there is an idea which we will see presently is well-founded, the idea that 'God' wills the existence of the 'Devil' and not the other way round, an idea which confers an evident primacy on 'God' in regard to the 'Devil'; but nothing in this dualistic perspective can explain why 'God' has need to desire the existence of the 'Devil' while remaining perfectly free.

Let us note the close relationship which exists between this dualistic conception 'God-Devil' and the aesthetic sense which distinguishes the human animal from the other animals. The aesthetic sense consists in perceiving the dualism, affirmation-negation, in 'form'. 'Satan' is deformed, that is to say of negative form, form in the process of decomposition, tending towards the formless. Man has an affective preference for formation (construction) as against deformation (destruction). The form of a beautiful human body is that which corresponds to the apogee of its construction, at the moment at which it is at the maximum distance from the formless and has not yet begun to return thereto. It is not astonishing that every morality should be in reality a system of aesthetics of subtle forms ('make a fine gesture', 'you have ugly propensities', etc.).

This dualistic conception 'Good-Evil', without the idea of the Superior Conciliating Principle, is that at which man's mind arrives spontaneously, naturally, in the absence of a metaphysical initiation. It is incomplete, and in so far as it is incomplete it is erroneous; but it is interesting to see now the truth that it contains within its limitations. If the intellectual partiality in favour of 'Good', due to ignorance, is erroneous, the innate affective preference of man for 'Good' should not be called erroneous since it exists on the irrational affective plane on which no element is either according to Reason nor against it; and this preference has certainly a cause, a raison d'etre, that our rational intellect ought not to reject a priori, but which, on the contrary, it ought to strive to understand.

Let us pose the question as well as we can. While the two inferior principles, conceived by pure intellect, are strictly equal in their complementary antagonism, why, regarded from the practical affective point of view, do they appear unequal, the positive principle appearing indisputably superior to the negative principle? If, setting out the triangle of the Triad, we call the inferior angles 'Relative Yes' and 'Relative No', why, when we wish to name the superior angle, do we feel obliged to call it 'Absolute Yes' and not 'Absolute No'? If the inferior angles are 'relative love' and 'relative hate' why can the superior angle only be conceived as 'Absolute Love' and not as 'Absolute Hate'? Why must the word 'creation', although creation comports as much destruction as construction, necessarily evoke in our mind the idea of construction and not at all the idea of destruction?

In order to make it clear how all this happens we will cite a very simple mechanical phenomenon. I throw a stone: two forces are in play, an active force which comes from my arm, a passive force (force of inertia) which belongs to the stone. These two forces are antagonistic, and they are complementary; their collaboration is necessary in order that the stone may describe its trajectory; without the active force of my arm the stone would not move; without the force of inertia belonging to the mass of the stone it would not describe any trajectory on leaving my hand; if I have to throw stones of different masses the stone that I will throw farthest will be that one whose force of inertia will balance most nearly the active force of my arm. Let us compare these two forces: neither of the two is the cause of the other; the mass of the stone exists independently of the force of my arm, and reciprocally; looked at in this manner neither is of a nature superior to the other. But the play of the active force causes the play of the passive force; if the play of my arm is action the play of the inertia of the stone is reaction. And what is true of these two forces in this minor phenomenon is equally true at all stages of universal creation. The two inferior principles, positive and negative, conceived in the abstract or existing apart from their interplay, are not the cause of one another; they derive, independently of one another, from a Primary Cause in the eyes of which they are strictly equal. But as soon as we envisage them in action we observe that the play of the active force causes the play of the passive force (it is in this that 'God' desires the existence of the 'Devil' and not the other way round). In so far as the two inferior principles interact and create, the positive principle sets in motion the play of the negative principle, and it then possesses in that respect an indisputable superiority over this negative principle. The primacy of the active force over the passive force does not consist in a chronological precedence (it is at the same moment that reaction and action occur) but in a causal precedence; one could express that by saying that the instantaneous current by means of which the Superior Principle activates the two inferior principles reaches the negative principle in passing by the positive. In this way we can understand that the two inferior principles, equal noumenally, are unequal phenomenally, the positive being superior to the negative. If the force that moves the sister of charity is strictly equal to that which moves the assassin, the helping of orphans represents an undeniable superiority over assassination; but let us note at the same time that it is the concrete charitable action which possesses an incontestable superiority over the concrete murder, while the two acts, regarded in the abstract, are equal since, so regarded, they are no longer anything but the symbolic representatives of equal positive and negative forces.

Arrived at this point we can understand that every constructive phenomenon manifests the play of the active force (action) and that every destructive phenomenon manifests the play of the passive force (reaction). It is for this reason that the man who has attained 'realisation' is as constructive, at every moment, as circumstances allow him; this man in fact is freed from conditioned reflexes: he no longer reacts, he is active; being active he is constructive.

Such and such a destructive demeanour on the part of the 'wicked' man can seem to show initiative, can appear to result from the play of an active destructive force. In fact this 'wicked' man acts in the first place in order to affirm himself (construction); it is by virtue of associations inaccurately forged in ignorance, that the act, necessarily begun in order to construct, results predominantly in destruction. If the stone that I wish to pick up is too heavy it is not the stone that is raised but I that am dragged down; my initial active force has none the less been directed towards lifting.

The man that has attained 'realisation', as we have seen, does 'good': but we note that this 'good' is a simple consequence of the inner process which has led the Divine Reason of this man to a constant activity in the process of realising his triple synthesis. This 'good' is a simple consequence of a liberating understanding integrated in the total being: and this understanding has done away with all belief in the illusory pre-eminence of the inferior principle or principle of 'Good'. This man no longer does anything but 'good' but precisely because he no longer idolises it and does not devote more attachment to it than to 'evil'. His demeanour is not that of a man who has trained himself to be a 'saint'; the demeanour of the 'saint', fixed, systematised, can cause ultimately more destruction than construction. The demeanour of the man that has achieved 'realisation' attains ultimately more construction than destruction (without this being in any degree a goal for this man) because it proceeds from a pure activity and he adapts himself to circumstances in a manner that is continually readjusted and fresh.

In short true morality is a direct result of intemporal realisation. The way of liberation could not be 'moral'. All morality, before satori, is premature and is opposed, on account of its restraints, to the attainment of satori. This does not mean to say that the man who strives for his liberation should endeavour to check his affective preference for 'good'. He accepts this preference with the same comprehensive intellectual neutrality with which he accepts the whole of his inner life; but he knows how to abstain from falsely transmuting this anodyne emotional preference into an intellectual partiality which would be in opposition to the establishment of his inner peace.

All that we understand here does not result in a condemnation of 'spiritual' or 'idealist' doctrines, which exalt virtue, goodness, love, etc., in the eyes of men of goodwill; that again would be an absurd intellectual partiality; man thinks and acts according to his lights. We state merely that these doctrines could not, by themselves, lead to the attainment of satori. If such a man desires, as he too has the right to desire, to attain satori, he must by his understanding, go beyond every doctrine which comprises a theoretical partiality in face of the Yang and the Yin. Zen proclaims: 'The Perfect Way knows no difficulty except that it denies itself any preference ... A difference of a tenth of an inch and Heaven and Earth are thereby separated.'