SelfDefinition.Org

Practical Memory Training

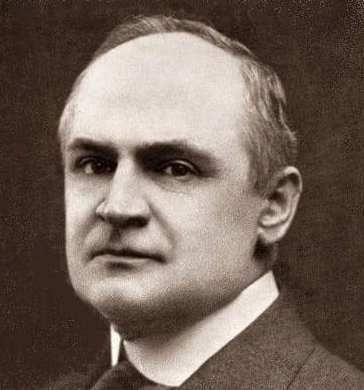

'Theron Q. Dumont'William Walker Atkinson

(1916)

Lesson 29 How to Remember Location

Psychology teaches us that there are certain faculties, or special phases, of the mind which perform certain special work, each doing its own particular work exclusively. Thus we have certain faculties which are concerned with the perception of color; others with the perception of size; others with the perception of form; others with the perception of sound; others with the perception of the relations of locality; and so on—each specializing along a certain definite line. It is now positively known that certain areas of the brain are devoted to special work of the kind just mentioned. So true this is, that if such certain centres are injured, the mind finds it very difficult to function along those special lines. For instance, certain injuries to the brain have resulted in complete loss of the sense of location or direction; others in the loss of recognition of names, words, etc.

Practical psychologists have lifted this subject out of the realm of theory, and have devised methods whereby any special faculty may be developed by appropriate courses of study, practice, exercise, etc. These things have been taken advantage of in this series of lessons, and form a part of the instruction for the development of special forms of memory. This, because, as I have repeatedly stated, the cultivation of any faculty of the mind results in an improvement of the kind of memory connected with that phase of mind, and vice versa. The explanation, of course, is found in the fact that each faculty of the mind maybe said to have its own memory—all forming parts of the whole memory, just as all faculties form part of the whole mind. The cultivation of a faculty, results in strengthening the memory allied with it; and, likewise, the cultivation of any phase of memory results in the strengthening of the particular mental faculty with which it is connected.

It follows, of course, that the general plan that I have outlined in the cases of name-memory, and face-memory, is also applicable to any and all forms of special memory. Whatever strengthens the perception of a faculty, also strengthens its correlated memory. The general rule once known, the rest becomes simply the method and details of application of the principle. The psychologists classify the perceptive faculties under the following order: Form, Size, Weight, Color, Order, Number, Tune, Time, Locality, Motion and Words. Interest, study, practice, and exercise will develop any of these perceptive faculties, and, of course, the memory attached to each. Apply the rules given under the lessons on Names, and Faces, respectively, to any of this list, and you will get the same result. Face-perception, of course, comes under the head of Form; and Name-perception under the head of Words, in the above classification.

Proceeding to the consideration of Locality-Perception, and Locality-Memory—the subject of this—I naturally give you the same kind of prescription as in the preceding lessons, by applying the general principles to the special requirements of Locality. This being so, I will not go into as many details as I did in the preceding cases, for I can now trust to the intelligence of the student to apply the general principles of memory training to this case without the need of tiresome repetition. In fact, in my personal classes, I make the pupils map out their own lesson on this subject, by drawing out of them the information they have already acquired—the Socratic Method, you will realize. But in these printed lessons, a little more detailed instruction is required, from the very nature of the case.

The faculty of Location performs the work of the perception and memory of Places, Positions, Locations, Directions, etc. It may be called "the geographical sense," although this limits it, in a way, for it is manifested in the sense of location of the heavenly bodies, as well as of the things of earth. Those in whom this faculty is highly developed, are able to quickly and readily perceive, and equally easily remember, the directions and locations of things, the places in which things exist, the order of position in space, land-marks, points of the compass, the general "lay of the land," streets, roads, water-courses, etc. Such persons never get lost or confused as to location or direction. They have the "sense of the North" fixed in their subconscious mind, and adjust other directions almost automatically. Seafaring men, hunters, trappers, explorers, and great travellers, have this faculty strongly developed. And, of course, their memory on these points is remarkably strong. Others, deficient in this faculty, are continually losing themselves, and getting "mixed up" regarding locations, directions, etc.

To those who are deficient in this phase of mental action, and memory, I would advise, first of all, the deliberate cultivation of INTEREST in all things related to the subject. Let them first begin to think of the direction of any place of which they are speaking or thinking, so that they may feel that it is "that way" from them. Also let them try to visualize the direction from one place to another, when they are speaking of different places. Let them study maps, making imaginary journeys from one place to another, following the lines of the railroads, steamships, or rivers, as marked on the maps. After having acquainted themselves with the different parts of the world, in this way let them make imaginary journeys "in their minds," without using the map. Let them plan out trips in this way, and then take them—mentally. Imagine that there is a hidden fortune awaiting you at some given place, and then see how you can reach this place as quickly and directly as possible.

Such persons should observe the various landmarks on the streets over which they travel. They should travel over new streets to take them to old destinations. Walks in strange localities will help in this way. Try to acquire the "homing sense," so that you will intuitively recognize the general direction of your home, from whatever point you may be at the moment. This sense is really a subconscious knowledge based upon the impressions placed within it by your interested observation, though you may not be aware of them afterward.

A little exercise with your pencil in making maps of the walk you have just finished, will help some. Take the map of your city or locality, and mark out a trip, which you should afterwards take without referring to the map. Hunt out strange corners, and streets, roads, and drives, your locality—you will soon grow interested the task, and will, at the same time, be strengthening your faculty and memory of location and direction. Play the game of travel by marking down the landmarks, etc., when you return. It will help to take these trips with a companion, each playing the game against the other, and trying to score a greater number of points of this kind.

If you are going on a trip away from home, far or near, prepare yourself by going over the trip by the aid of a map, before you actually start out on the journey. Fix in your mind the various points, stops, directions, etc., and compare them with the places when you actually reach them on your journey. You will find that a fresh, and entirely unexpected, interest will be awakened in this way. Study maps of the cities that you intend visiting, taking note of the principal points of interest noted thereon, their location, distance and direction from each other. Then travel over this mental route when you reach the place. It will develop a new, and very interesting, game for you.

I have met a number of persons who were perfectly familiar with the general location, direction, distances, etc., of cities which they had never before visited. Upon investigation, I always found that these persons were very fond of maps—had the "map habit" strongly developed—and when they reached a place, they always felt that they knew it, by reason of their preliminary mental visit by means of maps, guidebooks, etc.

Again, after you have visited a place, and returned home, try the experiment of re-visiting it in your imagination, and bringing before your mind's eye the general "lay of the land," direction, distances, location, etc. I have known persons who have been able, in this way, to reconstruct an entire trip of several thousand miles; while, on the other hand, I have known persons who seemed to be in entire ignorance of the road travelled, direction taken, or location of any point of even a short trip. Memory followed the interest, or lack of it, in each case.

In conclusion, I repeat the now familiar advice: Take interest; practice; exercise; make associations. That is the whole thing in a nutshell, in location as in names and faces. But remember that INTEREST is the grandparent of all of the other requisites. Secure the grandparent and the rest will come in due course of events. If you were hunting hidden treasure, your locality faculty and memory would grow like a gourd—for the Interest would-be there! Moral?