SelfDefinition.Org

The Practice of Zen

Garma C.C. Chang

Chang Chen-chi (1920-1988)

Four Vital Points in Zen Buddhism

Esta página en español: ..cuatro-puntos-vitales.htm

A great many misconceptions about Zen have arisen in the West over several vital points taken for granted in the East but not understood or appreciated by the Western mind. First, in the study of Zen, it is important to learn not only the teaching itself, but also something about the mode of life followed by Zen students in Oriental countries. Applied inwardly, Zen is an "experience" and a "realization," or a teaching that brings one to these states; but outwardly Zen is mainly a tradition and a way of living. Therefore, to understand Zen properly, one should study not only its doctrine, but also its way of life. At least a passing acquaintance with the monastic life of Zen monks would be a very valuable aid to a better understanding of Zen.

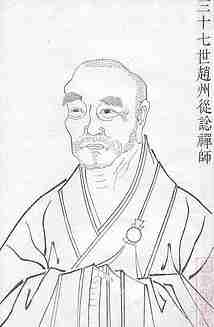

Chao Chou (778-897)

Zhaozhou Congshen

When reading Zen koans, we often come across the statement that a monk was immediately enlightened after hearing a certain remark, or after receiving a blow from his Zen Master. For instance, when Chao Chou heard Nan Chuan say "The Tao is not a matter of knowing or of not knowing ..." he was at once enlightened; when Hung Chou was kicked by Ma Tsu, he was at once enlightened; and so forth. This may give the impression that "Enlightenment" is very easy to come by. But these "little" koans, often consisting of less than a hundred words, are merely a fraction of the whole story. Their background was seldom sketched in by the Zen monks who first wrote them down, because the monks did not think it necessary to mention their common background to people who were brought up in the Zen tradition and knew it clearly. The monks thought that nobody could be so foolish as to regard "Enlightenment" as immediately attainable merely by hearing a simple remark such as "a stick of dry dung" or by receiving a kick or a blow, without previously having had the "preparedness" of a ripened mind. To them it was obvious that only because the mental state of a Zen student had reached its maturity could he benefit from a Master's kicks or blows, shouts or cries. They knew that this maturity of mind was a state not easily come by. It was earned with tears and sweat, through many years of practice and hard work. Students should bear this in mind and remember that most of the Zen koans they know are only the high-lights of a play and not the complete drama. These koans tell of the fall of ripened "apples," but are not the biographies of these apples, whose life stories are a long tale of delights and sorrows, pleasures and pains, struggles and bitter trials. The Zen Master shakes the apple tree and the ripened fruit falls; but on the swaying branches the unripened fruit will still remain.

One should always remember also that the majority of Zen students in the Orient are monks who have devoted their lives to the work of Zen. They have only one aim: to gain Enlightenment; they have only one business in life: to practice Zen; the life they lead is a simple, monastic one; and there is only one way through which they learn Zen – by living and practicing with their Masters for a very long period. Under these circumstances they see Zen, hear Zen, taste Zen, and even smell Zen all of the time. Before they become Zen "graduates," they live as "apprentices" with their teachers for many years. They have ample time and opportunity to ask questions and to receive instructions directly from their Masters. How can one fail to learn Zen when he spends his whole life under such ideal conditions? In addition, these student monks can travel at will to visit one Master after another until they find the one who can help them most. The celebrated Zen Master, Chao Chou, was said, even at the age of eighty, to have continued traveling to various places to learn more of Zen! [e] On the other hand, Hui Chung, the national Master of the Tang Dynasty, remained in a mountain hermitage for forty years. Chang Chin meditated for twenty years, thus wearing out seven meditation seats! These are concrete examples of actual Zen lives. These Zen Masters were no fools; they knew all the outcry concerning the "here and now," the "ordinary mind," and "abrupt Enlightenment." But still they persisted in working hard at Zen all their lives. Why? Because they knew from their direct experience that Zen is like a vast ocean, an inexhaustible treasury full of riches and wonders. One may behold this treasury, reach toward it, even take possession of it, and still not fully utilize or enjoy it all at once. It usually takes quite a while to learn how to use an immense inheritance wisely, even after being in possession of it for some time. This is also true in the work of Zen. Zen only begins at the moment when one first attains Satori; before that one merely stands outside and looks at Zen intellectually. In a deeper sense, Satori is only the beginning, but is not the end of Zen. This is shown clearly in the discourses of Zen Master Po Shan, and the discussion on "Zen Enlightenment," in Chapters II and III, respectively.

There is another important facet of Zen which has not yet been fully explained to the West. In the study of Zen, it is advisable to become acquainted with two Chinese terms frequently employed by Zen Buddhists: chien and hsing. Used as a verb, chien means "to see" or "to view"; used as a noun, it means "the view," "the understanding," or "the observation." Hsing means "the practice," "the action," or "the work." It, too, can be used either as a noun or as a verb. Chien in its broader sense implies the over-all understanding of the Buddhist teaching; but in Zen it not only denotes the understanding of Zen principles and truth, but often implies also the awakened view that springs from the "Wu" (Satori) experience. Chien, in this sense, can be understood as "seeing reality" or "a view of reality." But while it signifies the seeing of reality, it does not imply the "possession," or "mastery" of reality. A Zen proverb says: "Reality [Chinese: li] can be seen in an abrupt manner, but the matter [Chinese: shih] should be cultivated step by step." In other words, after one has attained Satori, he should cultivate it until it reaches its full maturity, until he has gained great power and flexibility (Chinese: ta chi ta yung). [Endnote 1-9] This after-Satori cultivation, together with the before-Satori searching and striving, is what Zen Buddhists call hsing, "the practice" or "the work."

Zen Master Yuan Chin said, "The entire work of Zen that one may accomplish in one's whole lifetime may be summarized in the following ten steps, which can be used as a yardstick to measure or judge one's realization and accomplishment. The ten successive steps [Endnote 1-10] are: [f]

1. A Zen student should believe that there is a teaching (Zen) transmitted outside of the general Buddhist doctrine.

2. He should have a definite knowledge of this teaching.

3. He should understand why both the sentient being and the insentient being can preach the Dharma.

4. He should be able to see the 'Essence' [Reality] as if beholding something vivid and clear, right in the palm of his hand; and his step should always be firm and steady.

5. He should have the distinguishing 'Eye-of-Dharma.'

6. He should walk on the 'Path-of-the-Birds' and the 'Road-of-the-Beyond' (or 'Road-of-Wonder').

7. He should be able to play both the positive and negative roles [in the drama of Zen].

8. He should destroy all heretical and misleading teachings and point out the correct ones.

9. He should acquire great power and flexibility.

10. He should himself enter into the action and practice of different walks of life."

Thus Zen work consists of two main aspects, the "View" and the "Action," and both are indispensable. A Zen proverb says: "To gain a view, you should climb to the top of a mountain and look from there; to begin the journey [of Zen] you should go down to the bottom of the sea, and from there start walking." Although the edifice of Zen is supported by these two main pillars, the "View" and the "Action," Zen teaching lays most of its stress on the former. This is attested to by the great Master, I Shan, who said: "Your view, but not your action, is the one thing that I care about." That is why the Zen Masters put all their emphasis on Satori and concentrate their efforts on bringing their disciples directly to it. Being a most practical and straightforward teaching, Zen seeks to brush aside all secondary matters and discussions and to point directly to chien – the seeing or viewing of Reality. This is shown in the whole tradition of Zen. The emphasis on the "View" is witnessed by innumerable Zen koans and Zen sayings. Perhaps the most expressive one is Master Pai Chang's remark: "If the disciple has a view equal to his Master, he can, at most, accomplish but half of what his Master has achieved. Only when the disciple has a view surpassing that of his Master is he deserving of the Instruction."

As long as one has this View within himself, he is in Zen; carrying wood, fetching water, sleeping, walking – all his daily activities have become the miraculous performance of Zen. Thus the plain and ordinary mind is the Buddha's Mind; "here and now" is the paradise of the Pure Land; without bringing the Trikaya [Endnote 1-11] of Buddhahood into being, one is equal to Buddha.

For the awakened Zen Buddhist holds the Essence of God, the Heart of Buddha, in his hand. With this invaluable treasure in his possession, what else does he need? This is why the outstanding Zen Buddhist, Pang Wen, said: "Carrying wood and fetching water are miraculous performances; and I and all the Buddhas in the Three Times breathe through one nostril." This high-spirited, bold View is truly the pinnacle of Zen.

The spirit as well as the tradition of Zen is fully reflected in its emphasis on chien rather than hsing. Therefore, though Satori is merely the beginning, it is nevertheless the Essence of Zen. It is not all of Zen, but it is its Heart.

Finally, Zen has a mystic or supernatural side which is an essential part of its nature. Without this it could not be the religion that basically it still is, and it would lose its position as the most humorous actor in the Buddhist play. The five stories that follow illustrate the Zen way of performing miracles and its cynical manner of poking fun at them.

Mount Wutai (Ching Liang)

A. Zen Master Yin Feng of the Yuan Ho period of the Tang Dynasty was in the habit of staying at Mount Heng, in Hu Nan Province, Central South China, in the winter; and at Mount Ching Liang in Shan Hsi Province, North China, in the summer. One summer, a revolution broke out as he reached Huai Ssu on his way to Mount Wu Tai [another name for Mount Ching Liang]. The insurgent general, Wu Yuan Chi, and his soldiers were fighting the national army. The battles went on, and neither side had as yet gained the upper hand. Master Yin Feng then said to himself, "I think I'll go to the front and try to reconcile them." So saying, he threw his staff up into the sky and, riding upon it, reached the battlefield in short order. The soldiers on both sides, awestruck at the sight of a flying man, promptly forgot about fighting. Their hatreds and ill will were thus pacified and as a result the battles came to an end.

After performing this miracle Yin Feng was afraid that such a demonstration might lead people into misunderstandings, so he went to the Diamond Cave of Mount Wu Tai, and decided to leave this world. He said to the monks there: "On different occasions I have seen many monks die when lying or sitting down; have any of you seen a monk who died while standing up?" They answered: "Yes, we have seen a few people who died in that way." Yin Feng then asked: "Have you ever seen anyone die upside down?" The monks replied: "No, we never did." Yin Feng then declared: "In that case, I shall die upside down." Saying this, he put his head on the earth, raised his legs up toward Heaven, balanced himself in an upside-down position, and died. The corpse stood there solidly, with its clothes adhering to it – nothing falling down.

The monks then held a conference over this embarrassing corpse, and finally decided to cremate it The news spread like wildfire, and people from near and far came to see this unique spectacle, all moved to astonishment by such a miracle. But the problem of how to take the corpse to the cremation ground still remained unsolved, as no one could move it.

In the meantime Yin Feng's sister, who was a nun, happened to pass by. Seeing the commotion, she pushed her way forward, approached the corpse, and cried, "Hey! You good-for-nothing scoundrel of a brother! When you were alive you never did behave yourself; now you won't even die decently, but try to bewilder people by all these shenanigans!" Saying this, she slapped the corpse's face and gave the body a push, and immediately it fell to the ground. [From then on, the funeral proceeded without interruption.]

Yun Men (864-949)

Yunmen WenyanB. Tao Tsung was the teacher of the famous Zen Master, Yun Men. It was he who opened the mind of Yun Men by hurting his leg. Later Tao Tsung returned to his native town of Mu Chow, as his mother was very old and needed someone to support her. From then on he lived with his mother and earned a living for her and himself by making straw sandals.

At that time a great rebellion broke out, led by a man called Huang Tsao. As the insurgent army approached Mu Chow, Tao Tsung went to the city gate and hung a big sandal upon it. When Huang Tsao's army reached the gate they could not force it open, no matter how hard they tried. Huang Tsao remarked resignedly to his men, "There must be a great sage living in this town. We had better leave it alone." So saying, he led his army away and Mu Chow was saved from being sacked.

C. Zen Master Pu Hua had been an assistant to Lin Chi. One day he decided it was time for him to pass away, so he went to the market place and asked the people in the street to give him a robe as charity. But when some people offered him the robe and other clothing, he refused them. Others offered him a quilt and blanket, but he refused these also, and went off with his staff in his hand. When Lin Chi heard about this, he persuaded some people to give Pu Hua a coffin instead. So a coffin was presented to him. He smiled at this, and remarked to the donors: "This fellow, Lin Chi, is indeed naughty and long-tongued." He then accepted the coffin, and announced to the people, "Tomorrow I shall go out of the city from the east gate and die somewhere in the east suburb." The next day many townspeople, carrying the coffin, escorted him out of the east gate. But suddenly he stopped and cried: "Oh, no, no! According to geomancy, this is not an auspicious day! I had better die tomorrow in the south suburb." So the following day they all went out of the south gate. But then Pu Hua changed his mind again, and said to the people that he would rather die the next day in the west suburb. Far fewer people came to escort him the following day; and again Pu Hua changed his mind, saying he would rather postpone his departure from this world for one more day, and die in the north suburb then. By this time people had grown tired of the whole business, so nobody escorted him when the next day came. Pu Hua even had to carry the coffin by himself to the north suburb. When he arrived there, he sat down inside the coffin, holding his staff, and waited until he saw some pedestrians approaching. He then asked them if they would be so good as to nail the coffin up for him after he had died. When they agreed, he lay down in it and passed away. The pedestrians then nailed the coffin up as they had promised to do.

Word of this event soon reached town, and people began to arrive in swarms. Someone then suggested that they open the coffin and take a look at the corpse inside. When they did, however, they found, to their surprise, nothing in it! Before they had recovered from this shock, suddenly, from the sky above, they heard the familiar sound of the small bells jingling on the staff which Pu Hua had carried with him all his life. At first the jingling sound was very loud, as if it came from close at hand; then it became fainter and fainter, until finally it faded entirely away. Nobody knew where Pu Hua had gone.

These three stories show that Zen is not lacking in "supernatural" elements, and that it shares "miracle" stories and wonder-working claims with other religions. But Zen never boasts about its achievements, nor does it extol supernatural powers to glorify its teachings. On the contrary, the tradition of Zen has shown unmistakably its scornful attitude toward miracle working. Zen does not court or care about miraculous powers of any sort. What it does care about is the understanding and realization of that wonder of all wonders – the indescribable Dharmakaya – which can be found in all places and at all times. This was clearly demonstrated in the words of Pang Wen when he said. "To fetch water and carry wood are both miraculous acts."

Many koans prove the disdainful attitude toward supernatural powers that Zen has adopted. Zen not only discourages its followers from seeking these powers, but also tries to demolish such powers if it can, because it considers all these "powers," "visions," and "revelations" to be distractions that often lead one astray from the right path. The following story is a good example of this spirit:

D. Huang Po [Huangbo Xiyun] once met a monk and took a walk with him. When they came to a river, Huang Po removed his bamboo hat and, putting aside his staff, stood there trying to figure out how they could get across. But the other monk walked over the river without letting his feet touch the water, and reached the other shore at once. When Huang Po saw this miracle he bit his lip and said. "Oh, I didn't know he could do this; otherwise I should have pushed him right down to the bottom of the river!"

Despite all their mockery and dislike of wonderworking acts and supernatural powers, the accomplished Zen Masters were by no means incapable of performing them. They could do so if they deemed it necessary for a worthwhile purpose. These miraculous powers are simply the natural by-products of true Enlightenment. A perfectly enlightened being must possess them, otherwise his Enlightenment can at most be considered as only partial.

The last story of this series is particularly significant.

E. Chiu Feng was a disciple-attendant of Master Shih Shuang. When Shih Shuang died, all the monks in his monastery held a conference and decided to nominate the Chief Monk there as the new Abbot. But Chiu Feng arose and said to the assembly, "We must know first whether he truly understands the teaching of our late Master." The Chief Monk then asked: "What question have you in mind concerning our late Master's teachings?" Chiu Feng replied. "Our late Master said, 'Forget everything, stop doing anything, and try to rest completely! Try to pass ten thousand years in one thought! Try to be the cold ashes and the worn-out tree! Try to be near the censer in the old temple! Try to be a length of white silk.' I do not ask you about the first part of this admonition, but only about the last sentence: Try to be a length of white silk.' What does it mean?" The Chief Monk answered: "This is only a sentence to illustrate the subject matter of the One Form." [Endnote 1-12]

Chiu Feng then cried: "See! I knew you didn't understand our late Master's teaching at all!" The Chief Monk then asked: "What understanding of mine is it that you do not accept? Now light a stick of incense for me. If I cannot die before it has burned out, then I'll admit I do not understand what our late Master meant!" Whereupon the incense was lighted and the Chief Monk assumed his seat, sitting straight as a pole. And lo, before the stick of incense was completely consumed, the Chief Monk had actually passed away right there where he sat! Chiu Feng then tapped the corpse's shoulder and said, "You can sit down and die immediately all right; but as to the meaning of our late Master's words, you still have not the slightest idea!"

If Zen is to be considered as the quintessential and supreme teaching of Buddhism, a teaching that can actually bring one to liberation from the miseries of life and death, and not merely as useless babble, good only for a pastime, it must produce concrete and indisputable evidence to prove its validity to all. Mere words cannot sustain a religion; empty talk cannot convince people nor uphold the faith of believers. If Zen had not consistently brought forth "accomplished beings" who, on the one hand, realized the Inner Truth and, on the other, gave concrete evidence of their Enlightenment, it could never have overshadowed all the other Schools of Buddhism in its motherland and survived for over a thousand years. Buddhist Enlightenment is not an empty theory or a matter of wishful thinking. It is a concrete fact that can be tried and proved. In the preceding story, when the Chief Monk was challenged by Chiu Feng, he courageously testified to his understanding by actually liberating his consciousness-soul from his physical body within a few minutes. Who, without having some inner realization of Zen Truth, could possibly perform such a remarkable feat? But, surprisingly, even this outstanding achievement failed to meet the standard of Zen! To be able to free oneself from life and death in their literal sense is still far from the objective of the Zen Masters' teaching!

Judging Zen from this standpoint, how pitiful we find the babblings of those "experts" who know nothing but Zen prattle, and who not only abhor the existence of this type of koan, but purposely misinterpret it in their "Zen" preachings and writings – or completely omit it as if it had never existed! It is suggested, therefore, that the reader of this book look carefully for the differences between genuine and imitation Zen – between the Zen which comes from the heart and that which comes from the mouth, between the Zen of concrete realization and that of mere words, between the Zen of true knowledge and that of prevarication. Drawing these discriminatory lines, the reader will no longer be mystified, or bewildered by false prophets of Zen.

The above analytical and somewhat conservative approach may be said with some truth to "murder" Zen. But it is the only way to present Zen authentically and at the same time make it a little clearer to Westerners who, with no other means at hand, must for the most part approach the subject intellectually and follow a safer, if slower, way than that of the East to find and take the first step on the journey toward Enlightenment.