SelfDefinition.Org

Conquest of Illusion J. J. van der Leeuw

Theosophical Publishing House, 1928

Chapter 6 Spirit and Matter

The Problem of Duality

The antithesis of a solid, tangible and visible world around us and an invisible, intangible and subtle consciousness or life within is so fundamentally the structure of our world and so utterly permeates our outlook on life that it hardly occurs to us to analyze or doubt it. We unthinkingly accept the two terms of that duality as really opposed and ask ourselves whence the duality arises, how its two elements are related and how one can affect the other.

The names given to the opposites in this duality of our daily experience vary; they may be termed spirit and matter, life and form, self and not-self, energy and mass, but fundamentally they are that duality which appears to be the main structure of our lives. In ourselves we are sharply aware of the two opposites as body and mind; our life appears to be sensation, coming to us from without, the body affecting the mind, and on the other hand action and volition, coming from within, the mind affecting the body. Instinctively we recognize the difference, whatever philosophical theory we may cherish, we cannot escape from the fact that to us this interaction between mind and body, between world within and world without, is a daily reality. Even the philosopher, who in his speculations should attempt to deny the fact of this duality altogether, will find himself painfully reminded of it each time the law of his members wars against the law of his spirit, when he does that which he does not want to do or does not do that which he wants to do. Each time we experience the struggle between the body and its desires and the mind with its decisions the duality of our lives is brought home to us, and no theory can reason away that experience.

In mechanics and physics we are confronted by the same fundamental duality in the terms of energy and mass. We know but too well that, when we wish to lift a heavy weight, energy or force is needed and the distinction between the inert, heavy and solid mass we desire to move and the intangible, invisible energy we use to move it is sharp and undeniable. In fact, we might say that there is not an experience in our daily lives which does not show this dual construction in some form or other. The consciousness we have of ourselves as being a self, the way in which we look upon all else as being not-self, permeates our very lives, is manifest in every one of our experiences.

It is therefore but natural that the relation between body and mind, or matter and spirit, should be the fundamental problem of philosophy, the most prolific of all philosophical questions; there is hardly a philosophy which has not some contribution to offer towards this true riddle of the sphinx-- divine head on an animal body.

To find an explanation of this most outstanding problem of our daily life is a necessity; all day long we are aware of mind acting on body and body acting on mind, of energy moving mass and mass resisting energy and, if we are at all awake to the wonder and mystery of life, we must feel an eagerness, an intense desire to know how this interaction takes place. Even if, later on, we are to find that there are serious flaws in the problem itself, even though we may find that the problem as it stands cannot be solved, yet the desire to know and the intensity with which we demand an answer are of the greatest value. It is only according to the intensity of our questions that our ultimate experience of truth will be. If we ask our philosophical questions in a casual and indifferent way, in the attitude 'that it would be interesting to know these things,' we shall certainly never emerge beyond a superficial intellectualism. Almost every one of us occasionally does ask some philosophical question of the profoundest meaning-the purpose of life, the origin of the world, the ultimate reality of spirit or matter or the measure of freedom of the human will. But in most cases the one who asks lives on quite happily, even though he may not find an answer or experience the reality. Such is not the way of true philosophy; unless we ask with our whole being, heart and soul and mind, unless we can hardly eat or drink or sleep unless we know, unless life is no longer worth living without the experience of living truth, we shall not gain it. We must desire truth more than life itself if we are to be worthy of experiencing it.

Read but in the Confessions how St. Augustine yearned for truth; he speaks of his 'most ardent pursuit of truth and wisdom,' says that he is 'struggling for the breath of Thy truth,' and exclaims when he questions the nature of time:

My soul is all on fire to be resolved of this most intricate difficulty. Shut it not up, O Lord God, O my good Father; in the name of Christ, I beseech thee, do not so shut up these usual, but yet hidden things, from this desire of mine, that it be hindered from piercing into them: and let them shine out unto me, thy mercy, O Lord, enlightening me.

And again, when he contemplates the problem of evil, he speaks of the 'torment which his teeming heart endured,' saying that 'no man knew how much he suffered.' Such is the attitude of the seeker after truth and such are they who find; as long, however, as the problem is to us but an intellectual puzzle to be solved as well as possible, so long shall our answers but be ingenious explanations and nothing more.

According to the type or mentality of a philosopher or of some particular period will be the answer given to the fundamental problem of duality ; unknown to himself the philosopher will be influenced in his logical and well-reasoned theory by his own spontaneous attitude towards this dual universe. It would be of interest if, some day, a history of philosophy could be written in which the philosophical doctrines held by the leading philosophers were to be shown as the inevitable product of their own innate tendencies, desires and difficulties, rather than of their profound reasoning and irrefutable logic. It is often our general outlook on life, the way we feel towards the world surrounding us and towards our fellow men, our aspirations and struggles, our achievements and failures, which determine our philosophy and its doctrines, not these doctrines which determine our outlook on life. We accept or evolve a philosophy of life because it provides a framework within which our spontaneous tendencies can work, even though we may feel convinced that we have been won over to them by the logic of their propositions and the strength of their proof. It would not be difficult to show how a Spinoza, Kant, Schopenhauer or Nietzsche was determined in his philosophical doctrines by virtue of that which he was rather than that which he thought out. St. Augustine's emphasis of original sin is as much the inevitable outcome of the incessant struggle which his passionate nature caused him, as Schopenhauer pessimism was the result of his unhappy experiences and failures, reacting on a mind that could not rise triumphantly over them and gain strength instead of cynicism out of them. Had Schopenhauer been happy in his first love he would never have written his scathing words about women, had St. Augustine succeeded in harmonizing his passions with his religious aspirations he would never have condemned the unbaptized infant to everlasting hell. It is our outlook that causes our philosophy not our philosophy which causes our outlook.

There is therefore an element of truth and reality in everyone of the more serious approaches to the problem of our dual universe. In an unsympathetic discussion and criticism of philosophical doctrine it is no doubt always possible to present them in such a way that they appear but as the futile fantasies of arid minds, but if we try to understand a doctrine from the mentality of the one who produced it we shall always see that for that mentality and from that standpoint the doctrine was relatively true.

Monistic Solutions

It is impossible to imagine that mind can influence body or body influence mind, energy act on mass or mass on energy, unless there is something which unites the two terms in a higher unity or reduces them to one. If matter and spirit, body and mind were a real duality, each being essentially and fundamentally different from the other, it would be unthinkable, not only that they should influence one another, but even in any way be aware of one another's existence. Since their interaction is a fact in our universe we must come to the conclusion that they are not true opposites, entirely different one from another, having nothing in common, but that there must be a unity underlying them somehow; our dual universe must be seen as a monistic universe, however we achieve that monism.

The most obvious ways of overcoming the dualism in our universe is to acknowledge only one of its two terms as real and to look upon the other as secondary, produced in some way by the first. Thus the materialist looks upon mind as a function of matter, the idealist upon matter as but an idea in mind.

There is a type of man who is intensely concentrated on this world around him, ever seeking to explore that world more fully, to discover and observe more facts about it, so that ultimately, by learning the laws governing that outer universe, mankind may gain a control over its environment. That type of man may be of the noblest, may be utterly dedicated to the service of humanity, willing to sacrifice life itself in the pursuit of truth, ready to be tortured and burnt at the stake in adherence to that which he knows to be true, and yet, in his intense and absorbed interest in the physical universe, he will very likely come to a solution of duality by recognizing only matter as real and looking upon spirit or life as a byproduct, an epiphenomenon.

There is a materialism, in the ethical sense of the word, which is synonymous with a coarse indulgence in the material pleasures of life; the man who desires but wealth and pleasure, food, drink and material comfort is in that sense a materialist. We should distinguish such a materialism sharply from a true philosophical materialism; the philosophical materialist may be ascetic in his mode of life, dedicated to others, utterly forgetful of himself in his endeavours to improve the lot of human kind, yet, in his approach to the fundamental problem of duality, he will consider the world of spirit, life or consciousness as vague and unreal, and proclaim matter to be the only and final reality, mind or consciousness being but a result of material processes. In his observation of the world around he sees that, when the material form is destroyed or impaired, life or consciousness no longer manifests itself and his conclusion is that with the destruction of the form the life which was its result has ceased to be also. To him human character is but the outcome of the functioning of the body; can he not prove that, when certain glands are atrophied or do not function properly, the character of the person in question changes accordingly, whereas the implanting of a fresh gland will restore the previous characteristics?

In this materialistic view of the universe the ultimate reality is the atom, the unit of matter. Yet when we ponder over the latest contributions of physics towards the nature of matter, when we read of the ultimate atom as a form of energy, charges of negative electricity moving round a positive core, we may well ask if the materialistic solution of the problem of duality can any longer be called materialistic. The materialist's definition of the ultimate material unit and the idealist's definition of the ultimate spiritual unit are not as different as we would expect. And who shall say that what one calls the monad and what the other calls the atom are not one and the same thing?

Thus, in a materialistic monism, the world of matter around us is seen as the one and only reality, life or consciousness as but a by-product of physical processes.

Very different is the solution of that type of man who is intensely concentrated on the world within. With some the cause of this may be a certain world-shyness, a fear for a' material world and for their fellowmen which causes them to shrink back into themselves; the idealism of such, however, is but a pseudo-idealism. Yet we must not under rate the measure in which failure to cope with the powerful material world surrounding man influences his outlook upon that world. World-negation and world-denial have but too often been the retreat from a world which was too much for man.

There is on the other hand a true idealism, which is rooted in an intense realization of life, consciousness or mind and its creative activity. That which absorbs the idealist most is not the diversity of material forms, not their accurate observation and classification, but the power of life or consciousness over these forms, the fact that in all evolution we, can recognize a dynamic, creative principle moulding form All from within, above all the outstanding fact that man himself can re-create this world of matter around him, can rise triumphantly over his environment. Thus the importance and reality of that outer world retreat into the background; life, spirit, or mind becomes the ultimate reality, matter or form but an idea existing in a mind. The objects surrounding us in the world which appears to us so real are denied an objective reality and are but seen as images or ideas arising either in our own mind or the mind of some superior Being. Minds and their ideas are the supreme reality in an idealistic monism, the idealist denies reality to the material world, looks upon it as secondary and upon mind or spirit as primary.

There are many shades, both of materialism and idealism, but the characteristics given above are typical for most; they solve the problem of duality by denying the reality of one of its two terms and presenting that as but an aspect or by-product of the other.

Matter and Spirit as 'Aspects'

There is, however, a third way in which unity has been sought and that is by looking upon the two, matter and spirit, or life and form, as opposite aspects of one neutral Reality, neither spirit nor matter. As the two poles of a magnet, the one positive and the other negative, so are the two eternally opposed aspects of the one supreme Reality. This view appeals to us instinctively, because in our daily experience so many things show this same duality of opposites manifesting as male and female, positive and negative, action and reaction, attraction and repulsion. Whether our response to such an appeal is philosophically justified we shall see presently; for the moment our aim is but to present this third approach to the mystery of duality which considers spirit and matter as opposite aspects of supreme reality. It is this doctrine which in Hindu philosophy we find represented by the Sankhya philosophy and which permeates the teachings of the Bhagavad Gita. Thus in its thirteenth discourse we read of 'the beginningless, supreme Eternal, called neither being nor non-being,' and a little further it is said:

Know thou that matter (Prakriti) and Spirit (Purusha) are both without beginning and know thou also that modifications and qualities are all matter-born.

Matter is called the cause of the generation of causes and effects; Spirit is called the cause of the enjoyment of pleasure and pain.

Here it is possible for spirit to influence matter or matter to affect spirit because they are aspects of one Reality; they have an Essence in common and through that which they have in common the one can influence the other.

It is this latter view which we find also in theosophical literature, such as Bhagavan Das's book The Science of Peace and Dr. Besant's Introduction to the Science of Peace; here 'Self ' and 'Not-Self ' are the terms given to the ultimate realities-there is an abstract universal Self and an abstract universal Not-Self, the Pratyagatma and the Mulaprakriti. Thus in Dr. Besant's work, A Study in Consciousness, we read:

All is separable into 'I' and 'Not I', the 'Self' and the 'Not-Self.' Every separate thing is summed up under one or other of the headings, SELF or NOT-SELF. There is nothing which cannot be placed under one of them. SELF is Life, Consciousness; NOT-SELF is Matter, Form. (p. 6.)

And again:

We think of a separate something we call consciousness, and ask how it works on another separate something we call matter. There are no such two separate somethings, but only two drawn-apart but inseparate aspects of THAT which, without both, is unmanifest, which cannot manifest in the one or the other alone, and is equally in both. There are no fronts without backs, no aboves without belows; no outsides without insides, no spirit without matter. They affect each other because they are inseparable parts of a unity; manifesting as a duality in space and time. (pp. 35-36.)

In this view everything belongs either to the universal Self or the universal Not-Self; the universal Self and universal Not-Self form two real divisions to one or other of which all created things belong.

This solution of the problem of duality again appears in many different forms and interpretations, of these the one expressed in the Bhagavad Gita and The Science of Peace is philosophically and ethically the most valuable. Where the deeper interpretation such as we find in those works is lacking, the third view degenerates into a superficial theory of two eternal aspects, spirit and matter which in man are eternally manifest as the animal, the body, on one side, and spirit, the mind on the other. It is clear that in such a misunderstood duality of aspects man's mode of life must be one which strikes a happy medium between spirit and matter, a compromise between the God within and the beast without. In this superficial interpretation the duality of aspects is looked upon as unchanging, whereas in the theosophical interpretation quoted above the two aspects are seen in the supreme reality of the creative Rhythm in which there is a return of spirit or self to itself, a conquest of body by mind, a very much superior ethical result from that which we find in the superficial interpretation.

However that may be, in some form or other, whether as parallelism, pre-established harmony or duality of aspects, the third approach to the problem of duality appears in a multitude of doctrines and philosophical theories. There are indeed many forms of each of the three main theories, each form presenting special features or qualifications profoundly affecting the standpoints presented above. Even so the three theories described are the main paths of philosophical approach to the problem of duality.

The Problem Itself Erroneous

Most of the theories offering a solution for the problem of duality in our universe, unhesitatingly accept the problem as it stands and apply their intellectual powers to solve the difficulty which is presented to it; they but too often neglect first to analyze the problem itself, the question as propounded, and to see whether the problem is correctly formulated. Let us then first analyze the duality which seems so evident to us and see how we come to conclude that there is indeed an objective universe, a world of matter without, and a world of spirit or life within.

We have seen in a previous chapter that the universe appearing around us is the image produced in our consciousness by ultimate Reality. When we dissociate this world image from the consciousness which produced it, when we externalize it and make of it an objective, outside world, entirely apart from our consciousness, we create a gulf which separates our objectivated world-image from the consciousness that produced it and in that separation we produce the problem of the relation of two apparently separate things--the material universe around us and our consciousness within. That apparent duality then becomes the basis of our dual universe and on that basis are erected the different questions and answers concerning it.

But in philosophy we have no right to accept as sacrosanct any problem which our intellect or our daily experience imposes upon us; on the contrary, it is our duty first to analyze and study the problem and see whether or not error and illusion have crept into the problem itself. We do but compromise ourselves when we attempt to answer a problem which has in it the element of error, we must first purify it of that error and then we may find it possible to approach reality.

In our interpretation of reality, our world-image, we undoubtedly experience a self within and a world of not-self without. This experience is real enough for us, but to assign to the Absolute a Self, which posits a Not-Self opposite to itself, is to transfer the illusions of our world-image consciousness into our philosophical investigation. In the Absolute, in ultimate Reality there is no such thing as a universal abstract Self, neither is there a universal Not-Self; self and not-self are concepts which have no place in the world of Reality, they are experiences of the individual creature in the world of the relative; to transfer them from that world of relativity into the world of the Absolute is a philosophical heresy. Neither can we look upon the two, universal Self and universal Not-Self, as two main divisions, to one or other of which all things belong; we shall see presently that there is nothing which is either self or not-self in itself; things but appear as self or not-self to us; self and not-self are experiences relative to ourselves and of value only with relation to the consciousness which experiences them. We may assign a Self Not-Self construction to the Consciousness which informs a universe, the consciousness of a solar Deity or Logos; there awe are still in the world of the relative. To transfer the, however, or rather attempt to transfer them, into the world of Reality, into the world of the Absolute, is impossible. They have no place there, they are flowers of illusion which cannot live in the world of Reality; we speak of a universal Self we do not speak of an ultimate reality but of an abstract idea which we ourselves distil from our daily experience.

Thus the first ghost to be laid is that of the antitheses of Self and Not-Self, or an objective universe without and a world of consciousness within. These are but concepts born of illusion and in our approach to reality we must overcome them first.

It is of interest to see how in modern physics the problem of duality has been overcome. The problem here concerns of conception of mass or matter on the one side and of force or energy on the other. Here, too, there have been attempts at reconciliation which tried to solve the duality by reducing one of the two terms to but a form of the other. Thus, on the one hand, we find the idea of force reduced to that of mass, Hertz saying definitively that what we denote by the names of force and energy is nothing more than the action of mass or motion; on the other hand we find the atoms explained, as for instance by Boscovich, as being but 'centres of energy,' thus reducing all mass or matter to a form of energy or force. Lately, however, the old and time-honoured antithesis of matter and energy has been questioned and the two are shown to be convertible, on into the other. Inertia, hitherto the outstanding characteristic of mass, is seen to be possessed also by energy, the inertia for very high velocities being found to vary with the velocity. Modern physics thus recognizes a mass of pure electro-magnetic origin, varying with the or velocity. Again, the breaking up of the atom releases energy and one of the possibilities of modern physics is the liberation of that energy appearing to us as matter, in which liberation that same matter ceases to exist as before. We may safely say that the new physics is thus transcending the old problem of the duality between matter and energy, not by reducing one to a function of the other, but by showing that they are mutually convertible.

Superficially it may seem strange that science, which deals with the world of phenomena should be able to overcome the problem of duality or at least come to recognize that the duality, so sharply defined in classical physics, is a fiction. But then we must not forget that modern physics is able to transcend its previous limitations by virtue of the new mathematics which it uses in its calculations and that in these new mathematics as well as in the theory of relativity based on them, the illusion which would make absolute that which is relative, has been overcome.

We must then cease to be fascinated by the problem of duality either in its scientific or its philosophical presentation, but, laying aside the questions, born of illusion, approach that Reality, where the questions are superseded in the experience of things as they are.

The Experience In the World of the Real

Let us then once again withdraw from the contemplation of our own world-image and turn inwards through our centre of consciousness, entering the world of the Real. This should be done not only in thought, but in reality; only thus can we experience in ourselves that which, when expressed in words, seems but an intellectual paradox. Whenever we try to approach the reality of some problem in the world of the Real we should by gradual and slow stages withdraw our consciousness from the contemplation of our world-image, turn it inwards and, through the void where there is no content of consciousness, pass into the world of Reality.

Here we are no longer conscious of anything; we are all things. When, in the world of Reality, we experience things as they are, there is no trace anywhere of either spirit or matter; there is not a certain group of things which is labelled 'matter' or 'not-self' and another group which is labelled 'self' in that world of Reality. There the entire distinction appears meaningless; it is but our relative being which, in our daily experience, makes us look upon certain things as being in themselves matter and upon others as in themselves spirit or Self. In the world of the Real we find no such differences, all things there are essentially the same, an atom of matter as well as a living being. They are all modes of the Absolute and their differences are not differences in being, but only in fullness of realization. Nowhere in this world of reality do we find a trace of a universal Self or a universal Not-Self; these are but intellectual concepts distilled from our daily experience. The piece of stone which appears to me as not-self in my world image and the consciousness which appears to me as self in that same world image are here experienced as essentially the same, there is nothing to mark one as self or another as not-self; the distinction seems a futile one. What we do experience is what has been described already: the simultaneous or eternal presence of all relativity in the Absolute, the everlasting, unchanging Reality of all change, growth or becoming, of all creation, which is seen as the very nature of the Absolute. In the world of the Real there is no more reason to call the Logos of a solar system 'Self ' as there is to call an atom of matter 'not-self; ' one and all are the eternal relativity of the Absolute which, in them, is limited as the relative.

If then all things are essentially the same why should we experience some as 'matter,' whence comes our awareness of matter as solid and hard, heavy and impenetrable, surrounding us as an outside world? If all things, whether we call them 'matter' or 'spirit,' are one and all modes of the Absolute, specifically the same, why then do some of them appear to us as spirit, others as matter, some as self, others as not-self, some as life, others as form? However much they may be the same in type in the world of the Real there is no doubt, as we explained in the beginning of the chapter, that they appear to us in our daily consciousness as a very real duality, specifically different.

When we consider this question in the light of our experience in the world of Reality we can say the following. It is the action of things in themselves upon us in the world of the Real which is objectivated in our consciousness as our world-image. When the reality which contacts us is superior to us, a fuller realization than we ourselves are, then the result produced in our consciousness is a sense of increased being; we have touched something greater than ourselves and have experienced an increase which we term 'life' or 'spirit.' When, however, the reality which we contact is of a lesser order than, we ourselves are, so that we are unable to express ourselves through it without restriction, then the result in us is limitation instead of expansion. This limitation is objectivated in our world-image as that which is outside us, which hems us in, the prison walls by which we are surrounded; matter or form. Thus we can characterize matter or form as the way in which a lesser reality appears to a higher, spirit or life the way in which a reality of higher order appears to one of lesser order. Spirit and matter are terms denoting a relation between different modes of the Absolute; as such they are exceedingly useful terms and have a very real meaning. When, however, we look upon them as objective, independently existing realities they become absurd and meaningless.

The very thing which is life to the lesser reality will be form to the higher; we who are life or self to the cells of our body are form or not-self to some greater being to whom we are but as cells in his body. It is therefore not right to say that a thing is matter or spirit, not-self or self as such, in itself; it can only be life or form, self or not-self with regard to something else, and it is only life or form with regard to that particular thing or group of things. We are once again confronted with the old and fatal mistake of forgetting the relativity of the terms we use and making them into absolute entities. Life and form, spirit and matter, self and not-self are exceedingly valuable terms as long as we understand that they denote but a relationship; they become dangerous and, full of error when we forget this and isolate them on pedestals as independent and essentially different realities. Having done that we can ask as many questions and create as many problems about them as we like; they one and all remain incapable of solution.

Matter and Spirit as Relations

It may help us to a better understanding if we compare the relativity of the terms matter and spirit to a mathematical relation. Since what we call spirit or life is but the relation of a superior mode to an inferior one and matter or form is but the relation of an inferior mode to a superior one we can express the relation in the following way:

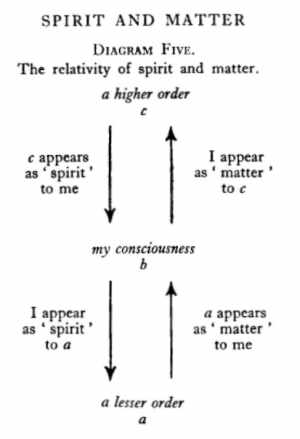

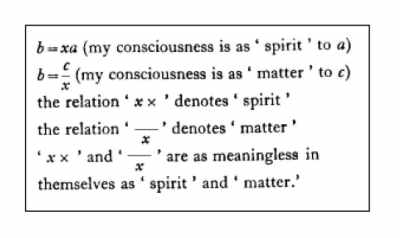

Diagram 5, The Relativity of Spirit and Matter

If three quantities a, b and c are related in such a way that b is x times a whereas c is x times b then it is clear that b stands in the relation of 'x times' to the quantity a and at the same time will stand in the relation of 'divided by x' to c. Let the relation of 'x times' stand for life or spirit and the relation of 'divided by x' stand for matter, then b will be related as spirit or life to a and at the same time will be related as matter or form to c. If b stands for our human consciousness, all things belonging to the a class will stand in the 'divided by x' relation to it, that is to say they will appear to us as matter, form, whereas all things belonging to the c group will stand in the 'x times' relation, the spirit or life-relation, to it. We, however, forget all about the relativity of our standpoint and gradually begin to believe that the spirit or 'x times something' relationship is inherent in c, in the same way as the 'divided by x' relationship is inherent in a, thus exalting that which is only a relation to an entity with objective existence. Having thus externalized and objectivated to an absolute existence outside of us that which is only a relation to us, we begin to ponder why some things are 'divided by x' (or matter) in themselves and other things are 'x times' (or spirit) in themselves, and our problem inevitably is devoid of sense.

Yet this is exactly what we do in daily life when we wonder what causes some things to be matter and others to be spirit, while in reality the true question would be why some things stand in the matter-relation to us and other things in the spirit-relation. Nothing is matter or spirit in itself, a thing can only be matter or spirit with regard to something, just as a mathematical quantity cannot be 'x times' in itself but must always be 'x times something' and similarly cannot be 'divided by x' in itself but must always be 'something divided by x.' To objectivate these relations into independent entities, to make them an inherent quality in the quantities a or c is as great an error as to believe that anything is in itself either spirit or matter, life or form. A thing cannot itself be a relation, it can only have a relation to something else. It is our passion for making an absolute entity of that which is only a relationship which causes the difficulty of our spirit-matter problems and the question of duality in general.

We can now see the absurdity of all attempts to proclaim the priority of either of the two relations as being the only real one, as if only the relation of 'x times' were real and the relation of 'divided by x' were but a by-product of the other relation. That is what we do when we say that only mind is real and matter is only a result of mind. In the same way it would be unreasonable and even absurd to say that 'x times' is but a product of 'divided by x,' that only 'divided by x,' or matter, was real and mind a by-product of matter. It is even more unreal to envelop the origin of spirit and matter with a metaphysical religious glamour and say that the Absolute in some mysterious way divides itself into two eternally opposite aspects of spirit and matter, or self and not-self. As well might we make abstract entities out of the relations of 'x times' and 'divided by x' and say a, that the Eternal shows itself in two opposite aspects, one called the 'x times' aspect and the other one the 'divided by x ' aspect. We show in our very attempts at such explanations the power of the illusion of our world-image over us and our subjection to that original sin of philosophy, which is to make absolute entities out of things which are only relationships. Thus I can but repeat that in attempting to solve the age-long problem of spirit and matter we compromise ourselves philosophically and condemn ourselves not only as being subject to the illusion of our world-image, but as guilty of the crime of lese majeste, which we commit when we try to transfer our illusions into the world of ultimate Reality.

Once again, our experience of certain things as matter, as form, as a solid objective universe around us and of other things as life or spirit within is a very real one indeed, and not for a moment should we make the mistake of trying to deny the reality of our experience of duality. But let us never forget that this apparent duality is but due to the way in which things appear to us, due to the relation in which certain things stand to us and affect us as increased being, spirit, or as limitation of being, matter, and that the same thing which is form to us may well be life with regard to something else and that we ourselves who are spirit with regard to our body, may well be matter with regard to some superior entity. Matter and spirit are terms denoting a relation, not abstract realities in themselves.

It is now clear how body may act on mind or mind on body, how force or energy may affect mass and mass resist energy. In the world of reality there is neither spirit nor matter, life nor form; there are only modes of being of and in the Absolute. That some of those, when contacted by a human consciousness, should appear as either of the relationships mentioned is but due to the place of our human consciousness in the scale of all relative things; when our place in that scale changes and we grow from human to superhuman beings these relations change with us. Yet in their eternal reality things have not changed at all, it is but in our experience of them, in our relation to them that they gain their meaning as matter, spirit, life or form. Our interpretations of Reality may vary, Reality remains and is ever unaffected by the names we give to the experience which we have of it.