SelfDefinition.Org

Conquest of Illusion J. J. van der Leeuw

Theosophical Publishing House, 1928

Chapter 2 From the Unreal to the Real

Woe! Woe!

Thou hast destroyed it!

The beautiful world!

Woe! Woe!

Thou hast destroyed! Destroyed!

Create! Create!

Build it again

In shy heart,

The beautiful world!

Create! Create! Create! – Goethe, Faust I.

Our Dual Universe

It is in the most familiar things of life that the deepest mystery lies hidden. If there is anything about which we feel sure, with which we think ourselves fully and entirely familiar, it is this world surrounding us, the world of our daily life. Around us we are aware of this world, solid and visible, a world so real to us that it would seem madness to doubt its reality. We can see and feel that world, lift the heavy and solid objects in it, hurt ourselves against their unyielding immobility and are impressed all the time by this fundamental fact of our existence--that there, opposite us, independent and apart from us, stands a physical world, utterly and entirely real, solid and tangible.

Within ourselves we are aware of another world, equally real to us, equally accepted as a basic fact of our existence. But it is a world of consciousness, of life, of awareness, a world which we associate with the feeling that we are 'we'. As a rule, however, our attention is not directed towards that world within, and for most of us it remains a vague and mysterious realm, out of which thoughts and feelings, desires and impulses, flashes of inspiration and sudden ideas seem to emerge, entering into our daily existence with a compelling power that will not be denied. These strange inner happenings also we accept as facts, knowing even less about them than about the solid world of 'material realities', in which we are so immersed and engrossed. We are thus faced by this strange fact--that the world of our own consciousness is unfamiliar to us, even through it is our very self, and that the world outside, which we assume to be not self, seems quite familiar and well known.

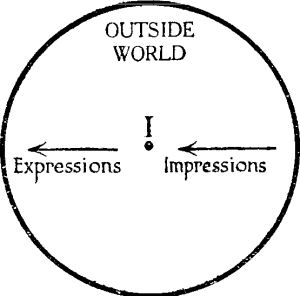

Such then is the fundamental structure of our daily life--a solid, tangible, material world without and a mysterious realm of consciousness within, forming a duality which most of us never come to doubt. In this primitive dualism we live our lives an we look upon our perceptions and our actions as an interplay between those worlds--sensations coming to us from the world outside and forming perceptions in our consciousness, from which again volition and action go forth to change and influence that outer world.

This sense of duality, of an outer and an inner world, is so familiar to us, enters so much into every moments of our lives, that, whenever questions arise with regard to the problems of life, we always, in those questions, assume and presuppose of this primitive duality as a fact which needs no proving, without even being aware that we introduce it. We unconsciously base our reasoning, yes, the very methods of our analysis and logic, on this fundamental duality which we accept because we have never thought about it. In the quest of truth, however, we must be utterly free from prejudice and ruthlessly sincere, never accepting a fact, cherished though it may be and hallowed by universal recognition, without first challenging its reality, even though such a challenge might appear superfluous. Only thus can we prevent error from entering into our very questions.

Diagram One: Interaction between the world and myself.

Let us then consider the two elements of our universe, the world of consciousness within and the world of appearances without, and see how we come to know of them. With regard to the consciousness or life side of our twofold universe there can be no doubt; the fact that we are something and somehow, is the basis of all our knowledge, of all our awareness. 'Cogito, ergo sum' is still the starting point of all investigations, the very words 'I think' already imply the basic fact, 'I am'.

In ordinary consciousness all I know is an unceasing, everflowing modification of my inner life, of my very being; my awareness, or state of consciousness, is different at every moment. I know nothing but these states of consciousness or awareness; nothing, idea or object, exists for me unless I am aware of it, that is to say, unless it is awareness in my consciousness.

It is difficult to realize this simple fact that, when we say we know a thing, whether as a sense of perception or as an idea, all we do really know is a state of consciousness corresponding in some way to the object or to the idea. We live and move and have our being in the world of our consciousness and it is the only world we know directly, all else we know through it. This means that all knowledge; we experience an awareness in our consciousness and thence derive the existence of something that has produced the awareness.

Hence our relation to the appearance side of our universe, the outer world, is very different from our relation to the consciousness side of it; the last we know directly, it is our very being, the other we know only indirectly, in so far as our being is modified by it in what we call 'awareness'. Therefore, while we cannot doubt the fact that we are aware of things and that we are experiencing modifications of consciousness, we must carefully scrutinize our conclusions about an objective universe around us which produces the perceptions in our consciousness. The latter are indubitable, the former but a conclusion which we rightly or wrongly derive from them. Yet, curiously enough, we feel perfectly confident about the objective universe around us, even though it is a derived knowledge, and feel somewhat uncertain as to the world of consciousness within; the stone at our feet is ever more real to us than our consciousness within. Yet we only know that stone in and through our consciousness.

The Way of Sense-Perception

Yet we feel convinced of the objective reality of the world surrounding us, 'just as we see it,' in fact, we forget all about our consciousness as intermediary between ourselves and the object and look upon the awareness in our consciousness as identical with the object itself. Thus, when we see a green tree, we do not doubt for a moment that the tree stands there, a hundred yards away from us, exactly as we see it, and we have gone a long way in philosophical realization when we can realize and not merely believe that the tree which we see is but the image produced in our consciousness by the tree which is and that the two are by no means identical.

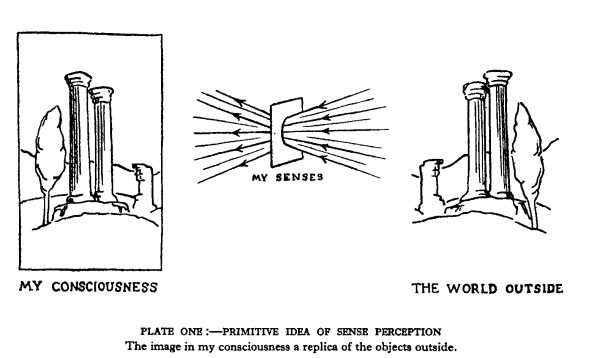

The primitive and unthinking way of explaining sense-perception implies that, through the senses, a faithful image of the world around us is reproduced in our consciousness in such a way that image and reality are exactly alike see Plate I). In order to explain this process still further we compare it to the action of a photographic camera, where through the lens an entirely accurate and faithful picture is reproduced on the sensitive plate. Satisfied with the explanation we sink back into our unquestioning acceptance of the world around us, glad that everything is so simple and never suspecting that we have not explained anything at all. How the image reaches our consciousness through the darkness of the sensory nerves and the brain matter is a question which does not even occur in the primitive explanation. And yet, even if the senses produced a faithful image of the world surrounding us, that image again would have to be perceived by the consciousness and with regard to the perception of that image we should find ourselves faced by exactly the same difficulty as with regard to the perception of the outer world itself. We have merely shifted the problem one step, and, to the unthinking mind, such a shifting or re-statement of a problem is generally quite acceptable by way of explanation.

Plate 1

However, the image which the senses give us of the world around can never be a faithful one; our senses are selective and can only interpret those elements of the world around us to which they are able to respond. Thus, in the case of sound and light, we need only look at a table of vibrations in air and ether to realize how extremely small the groups of vibrations are to which eye and ear react. With regard to all the other vibrations we are practically insensitive, we only know them by inference.

It is a very useful exercise to think ourselves into a state of consciousness, where those elements of the world around us, to which our senses respond now, would be non-existent and the contents of our world-image would be furnished by elements to which our present senses do not respond. Imagine two beings meeting and comparing their knowledge of the world, a human being with our five senses and an imaginary being with the senses we lack. Each of them would be aware of a world around him, each of them, unless they were philosophers, would be quite certain that he perceived the world exactly as it was there, outside, and that he perceived all there was to be perceived of it. Yet their two worlds would be utterly unlike; could we for a moment perceive the other being's world there would be nothing in it familiar to us or resembling any feature of our world. And yes, the other being would have as much right to call his world the real world, as we should have to call ours the world as it really is. But from the standpoint of reality no one has a right to call his world the world; it is his world and nothing more, his selective interpretation of reality.

With the understanding of this truth our primitive explanation of sense-perception as a faithful reproduction of the world around us collapses, and our world-image, far from being identical with the real world, becomes but our specific interpretation of that world; our world is but our version of the world.

It is well to ponder deeply over this very simple fact of the selectivity of our senses and thoroughly familiarize ourselves with the idea that what we see around us is not the world at all, but rather the peculiar interpretation of that world which we as human beings, because of the nature of our five senses, make. It is not sufficient to agree intellectually with this and say that the argument is clear and that we acknowledge it to be true; philosophy must be realization if it is to be worth anything, and the truth we realize must become part of our very consciousness. Our innate superstition that the world we see is the world indeed is so deeply ingrained in our nature that it will rise again and again and make us believe that our world-image is the world in reality. Our primitive illusions need to be rudely shaken before a wider knowledge can be born.

Even if our senses are selective and do but interpret certain features of the world around us we might yet be tempted to say that, in so far as they do interpret that world, they interpret it faithfully and that the colours we see or the sounds we hear are there, around us, exactly as we are aware of them. Even a superficial study of the physiology of sense-perception, however, is sufficient to break down this last stronghold of sense-realism. Since the problem is the same for all our senses we may take the eye, and the sense of vision connected with it, as representative of the principles of sense-perception in general.

The light-vibrations which reach the eye are focused through the lens and act on the retina behind the eyeball, causing structural and chemical changes in it. If, at this stage of the process of seeing, we, as it were, tapped the wire, we should as yet find no trace of that which later on will become our awareness of the green tree; all we find are structural and chemical changes in the rods and cones which form the upper layer of the retina. It is of the utmost importance to realize that the knowledge, so far conveyed to the body from the outer world, is contained in these chemical and structural changes, which in turn affect the optic nerve along which a message is conveyed to that area in the brain which corresponds to the sense of vision. Still there is no question of a blue sky or a green tree; all we can hope to find in the brain, if we tap the wire at this stage of the process, is the change in the particles of the brain matter which are affected by the message conveyed along the optic nerve.

Then suddenly we, the living individual, in our consciousness, are aware of the green tree or, as we express it, we 'see' the green tree. (Plate II.) This last stage is the great mystery of sense-perception, and neither physiology nor psychology has yet bridged for us that gap between the last perceptible change in the brain and our awareness of the object with its colours and shapes.

Even in the final stage of the physiological process, which is the change in the brain matter, there is no question whatsoever of colour, shape or form, there are only structural and chemical changes in the optical apparatus. It is only when we, the living creature, interpret in our own consciousness that final stage that there is the green tree, the whole world of light and colour around us. But there is no green tree until we reach that consciousness stage; there is, no doubt, some unknown reality which reacts on our senses and somehow produces in our consciousness the awareness of the green tree and will produce that awareness each time it reacts on our consciousness, but there is nothing to show that this unknown reality in any way looks like a green tree. For all we know it may be a mathematical point, having within itself certain properties which, react on a human consciousness, produce there the different qualities which make up the image of the green tree as we see it. We, however, substitute the image produced in our consciousness for the unknown reality without an make believe that we are perceiving that selfsame green tree which is the image produced in our consciousness, that is to say, we think we are perceiving as an objective reality that which we are projecting as an image in the world of our consciousness. We, as it were, clothe the nakedness of the unknown reality with the image produced in our consciousness.

The same facts, which are true for the sense of vision, hold good for our perception through any of the senses; thus there is no question of should but in our consciousness, no question of taste or smell but in our consciousness, no question of hardness or softness, of heaviness or lightness but in our consciousness; our entire world-image is an image arising on our consciousness because of the action on that consciousness by some unknown reality.

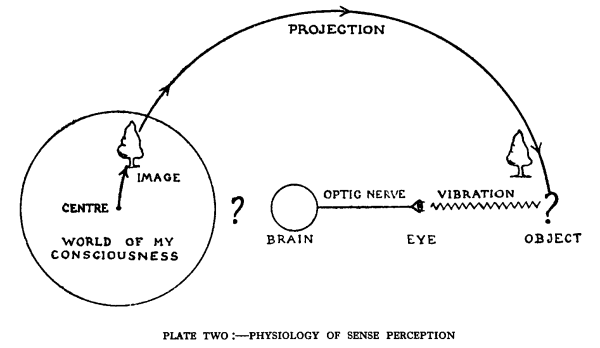

Our Body Too, Part of Our World Image

It is clear from a study of the physiology of sense-perception that all we know of the realities without, or of things in themselves, are the images produced by them in the world of our consciousness. But, curiously enough, even where we find this recognized and understood, we often find the physical body itself and the vibrations reaching it from the unknown objects outside, treated as if they were not images in our consciousness, but as if concerning them we knew everything. But how do we know of the existence of any vibration? By sense-perception, aided by scientific instruments which help us to see either the vibration itself or the effect produced by that vibration, showing us its nature. But surely this again is sense-perception and our perception of the vibration which reaches the eye, of the eye itself, the retina and the changes produced in it, of the optic nerve, and of the brain itself, takes place in exactly the same way as our perception of any object belonging to this mysterious outer world. They two: vibration, eye, retina, nerve and brain belong to that world of unknown quantities which in us produces images. Whether the image is that of a green tree, an optic nerve, or the grey matter in the brain does not matter, the relation of image to unknown reality is the same for all. The eye, the optic nerve, the brain and our physical body in general should not be singled out from this world surrounding us; they one and all belong to the world of unknown reality without, which produces in our consciousness that image which we call the world, but which is only our world-image.

Plate 2

It is the peculiar relation in which we stand to our own body, the intimate link we have with it and which we do not have with regard to any other object in the outer world, which makes us feel that we know all about its reality, even though other things may be full of mystery. We have an inside feeling of our body which we do not have with regard to a stone or a tree, our body appears to us as part of ourselves and we forget that is as much part of that outer world as the tree or the stone, and that our perception of it as a visible and tangible object takes place in just the same way as our perception of the tree or of the stone. Even the inner feeling we have of our body is but a variety of sense-perception which exists for our body alone. It too is but an awareness produced in our consciousness by an unknown reality, and with regard to it the same mystery exists as with regard to our perception of any other object in the outer world.

Plate 3

This means that we must somewhat revise our conception of the process of sense-perception. In it the object outside was supposed to be unknown, but the vibration which it sent out, the eye reached by that vibration and the nerve and brain affected in consequence, were all accepted as known and familiar quantities and never doubted as objective realities existing there, exactly as we perceive them. It was this ready assumption of the physical body as an independent reality existing without, which caused the gap between the last change in the brain and the image arising in our consciousness. This gap disappears when we realize that our physical body too, as we know it in its shape and colours, with all its qualities, is also an image produced in our consciousness by an unknown reality. Thus the situation becomes that shown in Plate III, where tree, vibration, eye, retina, optic nerve, brain and physical body in general, are one and all shown as images arising in the world of our consciousness.

Our World and The World

There is never a truth but carries in it the possibility of misconception. Thus it is true that the world which we 'see around us' is an image arising in our consciousness, with which image we subsequently deal as if it were an objective reality, existing apart from our consciousness. But there have been those who, catching a glimpse of this truth, have drawn the conclusion that therefore nothing but their own consciousness was real and that the world-image arising in their consciousness was in some way their own creation, in fact, that they lived in a world of their own making. This misconception, called solipsism (from solus, alone and ipse, self, meaning the outlook which recognizes only my own consciousness as real) is manifestly absurd; were it true that this world surrounding me is my own spontaneous creation. I should be capable of varying that creation at will, and if a tree, or a stone, or any of my fellowmen displeased me I should be able to eliminate them by an effort of the will ceasing in fact to create them. The solipsist is right in saying that what most people conceive to be an objective reality surrounding them is in reality their world-image, but he omits the second and greater truth, namely--that this world image is produced in our consciousness by the action upon that consciousness of an unknown reality, the real world or world of things in themselves. It is perfectly true that what I take to be an objective world is only the world-image produced in my consciousness, but it is equally true that this world-image is determined in its character by the nature of the things in themselves; it is my interpretation of them, partial and imperfect, but not containing anything which is not determined, in principle or in essence, by the thing in itself. Every phenomenon on my world-image is intimately and continually connected with a very real thing or event in the world of reality, and the fact that at some moment I might cease to produce a world-image in my consciousness does not for a moment affect conditions in the world of the Real.

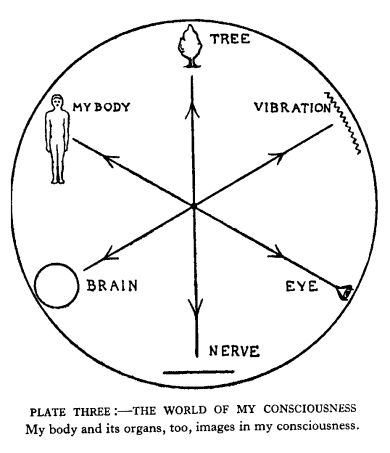

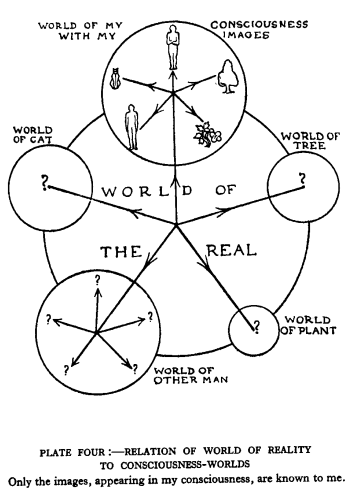

Plate 4

The conception of all that surrounds us as image in our consciousness was represented in Plate III; we must now go a step further and recognize that there is a world of the Real, which, through my consciousness, produces the different images in it. In Plate IV the world of our consciousness with its many images is shown in its relation to the world. The smaller circles at the end of the rays from the center symbolize the consciousness-worlds of different creatures, more or less limited according to their stage of evolution. In each of these consciousness-worlds a world-image is produced by the action of the things in themselves on that particular consciousness; each creature only knows its own world-image.

When, therefore, an event takes place in this world of Reality there is produced in the consciousness of each creature concerned an awareness, or image, which is the event as we 'see' it.

We must not misunderstand this. When I take up a book and drop it on the ground only one event takes place and that is the event as it is in the world of the Real. There is nothing unreal about that event; it is entirely, wholly and thoroughly real. But my awareness of the event, the way in which it presents itself in my world-image is my interpretation of the real event, and that interpretation is only relatively real, real for me, not real in itself. When then, in my world-image, I am aware of my hand grasping the book and dropping it on the ground, what really happens is that in the world of the Real an interaction takes place between that which I am in that world, the at which my body and consequently my hand is in that world, and that which the book and the ground are in that world, and that interaction or event is the one and only real event which takes place. What appears in my world-image is my version of it, in which version the unity of the event is broken up in measures of time and space and in a multitude of qualities. Then I externalize my awareness of the event in itself and that externalized image becomes for me the event itself. Unreality or illusion never resides in the event, or thing in itself, nor even in my interpretation of it, which is true enough for me, but in the fact that I take my interpretation to be the thing in itself, exalting it to the stature of an absolute and independent reality. Referring again to Plate IV we can see how an event, affecting all the creatures would produce a different version or image in the consciousness of each, though the event itself remains one and the same. In fact, though the real world is necessarily the same for all beings, the interpretation of that world must always be different for each.

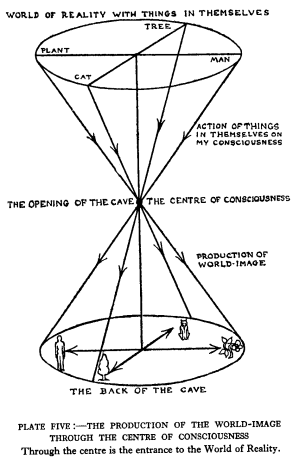

Plate 5

The relation of the real world to our consciousness and the image produced in it, is again shown in Plate V, but only for one particular consciousness. In it we see how the things in themselves, as they exist in the world of the Real, act on our center of consciousness and, through it, are projected as images in the world of consciousness, thus forming our world-image. It is clear how, through our consciousness, all things are as it were turned inside out; instead of being aware that they act on us from within we gaze upon the image we have produced and wonder how it influences us from without. It has become our fatal habit thus to look outwards upon the images produced in our consciousness and to forget entirely that they are projected there by the action upon our consciousness of things in the world of the Real. Thus, we are only aware of our own world, and, like the prisoners in Plato's cave, we are so used to gaze upon the back wall of our cave and see the shadows moving there, that we forget and even deny the possibility of turning round and knowing the reality which casts the shadows.

It is in his Republic that Plato uses this image, in which he compares men to prisoners who live in a cave and are bound in such a way that they can only see the back of the cave, not its opening. Behind them the procession of life moves by, different creatures pass and different events take place. The prisoners cannot see all this, but they do see the shadows cast upon the back of the cave. These shadows are reality to the prisoners, for they are the world, and since they have never seen anything else, it does not even occur to them that there can be another world. They may have come to know the different shadows by name and may even have built up certain knowledge on their observation of the regularly recurring shadows. But all the time, though their knowledge and their observation must necessarily have a certain relation to the reality outside, they deal with shadows and not with real things.

From time to time a prisoner feels the urge to free himself from his bonds and explore the other side of the cave. If he succeeds in doing so he discovers the great secret; that there, outside the mouth of the cave, is a magnificent world of reality, a world of dazzling light and beauty, and that which he used to see on the back wall of the cave were not real things at all, but only shadows. In the beginning his eyes, unused to the light of the real world, would be as blinded; he would only be aware of light everywhere. But gradually, as he begins to get used to this new world, he learns to distinguish between its creatures and objects, is colours and shapes, and comes to know that world in all its rich variety. Can we not imagine how, inspired by the wonderful discovery he has made, the erstwhile prisoner would go back to those who are still imprisoned in the cave and tell them, full of joy, of the glorious world he has found outside? But they would only laugh and call him mad; they know well enough that the only world is the world they see on the back of the cave and that those who would discover other worlds, and call their world a shadow-world, are but dreamers.

Our life is like that of the prisoners in the cave; we too see only the back of the cave, the wall of our own consciousness on which dance the shadows, the images cast there by the reality which we do not behold. We have come to know the play of these shadows so well that we have been able to build up an entire science concerning them. This science is right in so far as the shadows have a vital relation to the reality that cast them, but it is ever doomed to find itself confronted by mysteries, which in the world of shadows can never be solved, unless some who have seen the real world introduce into these sciences a wider knowledge. But we are impatient and incredulous when anyone would tell us that the world upon which we gaze is not the world of her Real, but only our world-image. Yet among us too evidence is not lacking of men, who, throughout the ages, have found freedom from their bondage, who have conquered illusion and discovered that world of Reality of which this world of ours is but a shadow or image, cast in the cave of our consciousness.

Illusion and Reality

We must, however, be careful about the way in which we characterize this our world as illusion, in fact, the danger of an incomplete statement and subsequent misunderstanding is so great that it hardly seems possible to state the relation as it truly is.

When we say, 'this world around us is unreal, it is illusion,' we make a misleading statement; when we say 'this world is real, it is not illusion,' we are even more misleading. Yet, if we were to think of this world as a strange mixture of real and unreal, that thought would be the most misleading of all.

To begin with, the world itself is real; there is nothing unreal whatsoever about a chair or a table, a tree or a stone, about all that which we call the physical world. It is a common mistake to characterize the physical world as unreal, or less real, and some mental or spiritual world as more real. The physical world in itself, the chair and the table in themselves, the stone or the tree in itself, are one and all as real as I am myself. But what I usually call the table, the chair, the stone or the tree is the image produced in my consciousness by the table, chair, stone or tree as it exists in the world of the Real. These images are only relatively real, that is to say they are real for me, in so far as they are my interpretation of the thing in itself, the shadow cast in my cave. It is when I begin to look upon this image in my consciousness as an outside reality, and identify it with the thing in itself that illusion enters. Then, in contemplating my image of the thing, I believe myself to be dealing with the thing in itself. This illusion, therefore, is neither in the thing in itself, nor in the image produced in my consciousness by that thing, but in my conception of the image in my consciousness as the thing in itself; as an object existing independent of my consciousness.

This then is the structure and relation of the real world and our world. There is a world of Reality, which would, for the purposes of distinction may have to be subdivided into different 'worlds' later on, but it is essentially one world, the only world, and whatever subdivisions we may find fit to make in it are not marked by labels in that real world, but are marked by our own associations and relative standpoint. That one world is the world as it is; in it things are as they truly are. That world is Life or Truth, or whatever else we may call ultimate Reality; that world is the Absolute, for there is all that is or was or shall be. In that world there is interaction between the different creatures and objects and as a result of that interaction every creature becomes aware in his consciousness of a world-image, the shadow cast by reality. Since, however, that shadow play is all we normally know of the real world we identify it with that real world and look upon it as a reality independent of our consciousness and standing outside us. That is the great Illusion.

Our world-image is thus the way in which we interpret reality. The many qualities of material objects, their distances and dimensions in space and their change in time, all that belongs to our interpretation, to our image. The tree in the world of the Real is not fifty feet high, its leaves are not green and smooth, its trunk is not rough to the touch and hard and it does weigh so many hundredweights. All these qualities are my interpretation of the tree in itself and are elements of my world-image. The tree in itself as it exists in the world of the Real may be pictured as a mathematical point, but there is that within it which, each time it reacts upon me, produces in my world-image a certain group of qualities of sound, touch, weight and certain measurements in space together with a certain change or growth in time. It is my particular constitution as a human being which causes me to produce just this type of image; the same tree in itself no doubt produces a different image in other creatures of whose existence I may not even know.

Because of the fundamental illusion which considers my world-image as an independent reality I come to look upon my image of the tree as if it were the tree itself, I assume space and time and the rich variety of sense-qualities to be independent realities existing there outside me, and I imagine events to be happening within their framework. Having thus objectivated and separated from my consciousness that which is indissolubly part of it I find myself hedged in by problems which no master-mind can ever solve, since they, one and all, are wrong problems, vitiated from the start by illusion. That is why the beginning of philosophy must be a clear understanding and even experience of the relation of our world-image to ourselves and to the world of the Real. Unless that is thoroughly clear to us from the beginning and becomes in very truth part of our consciousness we shall find ourselves led astray at each subsequent step. But our philosophy must be more than a mere intellectual understanding, every truth to which we attain must become an experience in our consciousness; thus alone can philosophy be vital and of real value in human life.

The Experience of the World of the Real

If it is true that our world-image is indeed an image produced in the cave of our consciousness by a reality beyond, it is evidently our first task, to thread, not merely in thought but in reality, the path leading to the world of the Real. It is here that so many philosophies fall short; they seem satisfied with having propounded their doctrine and do not feel the necessity of the doctrine becoming reality and experience. Often such philosophical doctrines are but an intellectual structure, strange to life and not the outcome of experience in our own consciousness. Yet such experience should not only be the basis of any philosophical assertion, it should also be the final test of any doctrine.

If once again we look upon Plate V and see how our world-image is projected around us in our consciousness we can see the way we have to go; we must withdraw ourselves from the enticing images of our own production and turn towards that center through which the production of our world-image takes place--the depth of our consciousness. That, in the beginning, will be the most difficult part--to abandon for a while our world-image, to relinquish this gay spectacle of time and space and the endless variety of sense-qualities. We must renounce all that, renounce sight and hearing, touch and taste and smell, renounce all that is phenomenon, appearance, image: this entire outer world. But even that is not enough. Our world-image is threefold, there is what we call the physical world, there is the world of our emotions and there is the world of thought. Most of us have not yet developed waking consciousness or self-consciousness in the world of emotions and in the world of thought, but even so they are as much or as little an outside world as what we turn the physical world. In the simple experiment of thought-transference we can test for ourselves the relative objectivity of a thought-image; in the imparting of a strong emotion from one person to another, a thing we often experience where masses of people are gathered, we can see that an emotion is not the vague inner thing we often think it to be, but objectively real. Thus we must not only renounce the physical world with its sense-qualities, but also the crowded worlds of our emotions and thoughts--we must cease for a while to allow any emotion to move us or any thought to modify our consciousness. Difficult as is the renunciation of our physical world-image, the withdrawing from the worlds of our emotions and thoughts is harder still and requires regular and repeated attempts, stretching sometimes through many years until success is gained.

Let us then do what so few ever do in our hurried civilization--be alone and be silent. So should relax all effort, and renounce all sensation coming to us from without, still our emotions and our thoughts and sink back into the depth of our own consciousness, like a diver sinking deep into the cool dark waters.

When thus we sunk back into the depth of our own consciousness we come to a state in which nothing seems to be any more, in which we ourselves seem to have lost name and form and all characteristics. We come to the great Void. It is the 'grey void abysm' of which Shelley sings in his "Prometheus Unbound,' in the haunting "Song of the Spirits' which leads Asia and Panthea down into the depths of consciousness:

To the deep, to the deep,

Down, down!

Through the shade of sleep,

Through the cloudy strife

Of Death and of Life;

Through the veil and the bar

Of thing which seem and are,

Even to the steps of the remotest throne,

Down, down!Through the grey, void abysm,

Down, down!

Where the air is no prism,

And the moon and stars are not,

And the cavern crags wear not

The radiance of Heaven,

Nor the gloom to Earth given,

Where there is One pervading, One alone,

Down, down!

When we reach the Void within, the state in which nothing more seems to be, it would appear as if we were surrounded on all sides by a blank wall and as if it were impossible to proceed any further. Then comes the moment when we must break the habit of ages and, like the prisoner in the cave, dare to turn our faces the other way and find the way out of the cave, find reality, freedom.

We have to move in a dimension we did not know before; the prisoner in the cave never realized that there was such a thing as a world behind him and we can well imagine how, when first he strives towards freedom and ceases to contemplate his shadow-play on the back wall of his cave, nothing seems to remain to him and he too finds himself in the great Void.

The first part of our journey towards reality is the surrendering of our world-image and the turning inwards until we reach the center of consciousness, the second is to pierce through that center and find the reality which, acting on that center produces the world-image in the cave of our consciousness. The experience of going through the center of consciousness and emerging, as it were, on the other side very much one of turning inside out. In our ordinary consciousness we are turned outwards towards the world-image which we externalized around us. In going through our consciousness the entire process is reversed, we experience an inversion, or conversion, in which that which was without becomes within. In fact, when we succeed in going through our center of consciousness and emerge on the other side, we do not so much realize a new world around us as a new world within us. We seem to be on the surface of a sphere having all within ourselves and yet to be at each point of it simultaneously

It is impossible to describe the world of Reality in the terms of our world-image, which is the only language at our command. As Kabir says: 'That which you see is not, and for that which is, you have no words' (Tagore, 49). It is a world of pure Beauty, yet, how express beauty without shape, colour or sound, the Beauty unbeheld' of which Shelley sings? When we experience it we feel that now we know beauty for the first time and that what we used to call beauty in our world image was but a distorted shadow. But the outstanding reality of our experience in the world of the Real is the amazing fact that nothing is outside us. There is distinction between different beings, the things in themselves, there is multiplicity, there is all that which in our world-image produces the rich variety of outer forms and yet it all is within ourselves; and when we desire to know we are that which we know.

Throughout the ages mystics have attempted to describe their vision of reality and in Bucke's work, Cosmic Consciousness, he gives at length the descriptions of the mystic state by those who have experienced it. The evidence is too great to speak of these experiences as being of a 'merely subjective' value; they are subjective, as all true experience, is, but, like all great experience, they are objective in value and validity.

Plotinus, the father of intellectual mysticism, thus describes the vision of Reality, or the 'Intelligible "World' as he call its, in Ennead v. 8, 4:

In this intelligible World everything is transparent. No shadow limits vision. All the essences see each other and interpenetrate each other in the most intimate depth of their nature. Light everywhere meets light. Every being contains within itself the entire Intelligible World, and also beholds it everywhere, every thing there is all, and all is each thing; infinite splendour radiates around. Everything is great, for these even the small is great. This world has its sun and its stars; each star is a sun and all suns are stars. Each of them, while shining with its own due splendour reflects the light of the others. There abides pure movement; for He who produces movement, not being foreign to it does not disturb it in its production. Rest is perfect, because it is not mingled with any principle of disturbance. The Beautiful is completely beautiful there, because it does not dwell in that which is not beautiful.

In the mystical experience of the world of reality we use a faculty of knowledge which is only beginning to be born in humanity. It is intuition, knowing by being, realization, the 'Tertium Organum' of Ouspensky. Without the use of that faculty the world of the Real cannot be know, but we must not say that the things in themselves cannot be known at all. The ring-pass-not, which Kant drew around the thing in itself exists only for those in whom the new faculty or organ of knowledge is not awakened, it is by means a spell laid on all future humanity, denying to them for ever the possibility of knowing the Real.

One truth emerges from our experience like a mountain peak from a surrounding plain. We now realize that no philosophical problem whatsoever can ever be approached in our world-image, that there is but one way of approaching these problems which is: to conquer the illusion of our world-image, to enter the world of the Real and, in that Reality, to experience living Truth.

It is only in the Vision from the mountain top that we know reality. But when we climb The Mount of Reality we must leave behind us all the load of illusion which would weigh us down in our climb and prevent us from ascending. The burden of our cherished illusions cannot pass through the customs of the real World, we must leave behind all that belongs to our world-image, else we shall not reach the mountain top, we shall not see the Vision.

That Vision alone is life, the Vision is Truth, Beauty, Peace and Joy, having seen it we have entered the world where we truly belong. When again we return to our daily life and play the game of time and space in our world-image, as we needs must do, we shall yet, through the world-image, ever see the Vision of Reality which we have gained; through every creature, every object, every event of our world-image a new meaning and a new beauty will shine forth. Such is the gift of Reality even to our world of illusion.